Three Titans of Viennese Modernism

Josef Frank, Josef Hoffman and Adolf Loos

Adolf Loos, Image © Villa Winternitz,

At the turn of the 20th Century, the Hapsburg family’s Austro-Hungarian Empire ruled nearly 700,000 square kilometres from the Tyrol to Italy, from Ukraine to Transylvania, 52 million people. It may have seemed invincible and unchangeable, but deep currents of change were running through philosophy, literature, the visual arts, and the sciences and, of course, politics, increasingly straining the status quo of absolute monarchy.

The nationalist aspirations of many of the Empire’s dozen plus subject peoples, slow economic improvement and the wretchedness for many of industrialisation formed a rich mulch for the growth of revolutionary and social democratic politics. Out of this increasingly febrile atmosphere of new ideas, Viennese modernism, the Wiener Moderne, emerged as a distinct counterpoint and avant-garde response to the sclerotic official culture of the Empire. An artistic subset of the broader cultural movement was the Viennese Secession. Figures who emerged from the Vienna Secessionist movement continue to hold significance today.

Adolf Loos

Adolf Loos was a pivotal figure regardless that he was only briefly involved in the movement and subsequently very publicly turned his back on the Secessionists. Born in Brno, his adopted home was Vienna. The three years he spent in America shaped his views and led the way for his embrace of modernist architecture in Europe. Loos rejected the typically Viennese overly decorative style to embrace the philosophy of Louis H. Sullivan, the American architect who coined the phrase ‘form follows function’. Loos’s rejection of the pervasive Viennese architectural style culminated in his essay ‘Ornament and Crime’. His role in bringing modernism to Europe cannot be underestimated, and two of his houses, Looshaus in Vienna and Villa Müller in Prague, are perfect illustrations of his minimalist approach and remain iconic examples of modernist architecture.

Adolf Loos fireplace in the dining room of Wienbibliothek Musiksammlung Image Mihaela Nancu CC BY SA 4.0

Plezeň, Czech Republic, apartment for the Vogl family designed by Adolf Loos CC BY SA 4.0

We’re going to look at two other titans who share a first name, Josef Hoffmann and Josef Frank. They were extraordinarily gifted modernists; both were controversial within their own lifetimes, but Hoffmann didn’t do enough to distance himself from the darkness that swallowed up art and design, politics and peace after the 1938 Anschluss. In fact he sought to ingratiate himself with the Nazis.

Villa Muller Prague, Adolf Loos, CC BY SA 3.0

Josef Frank

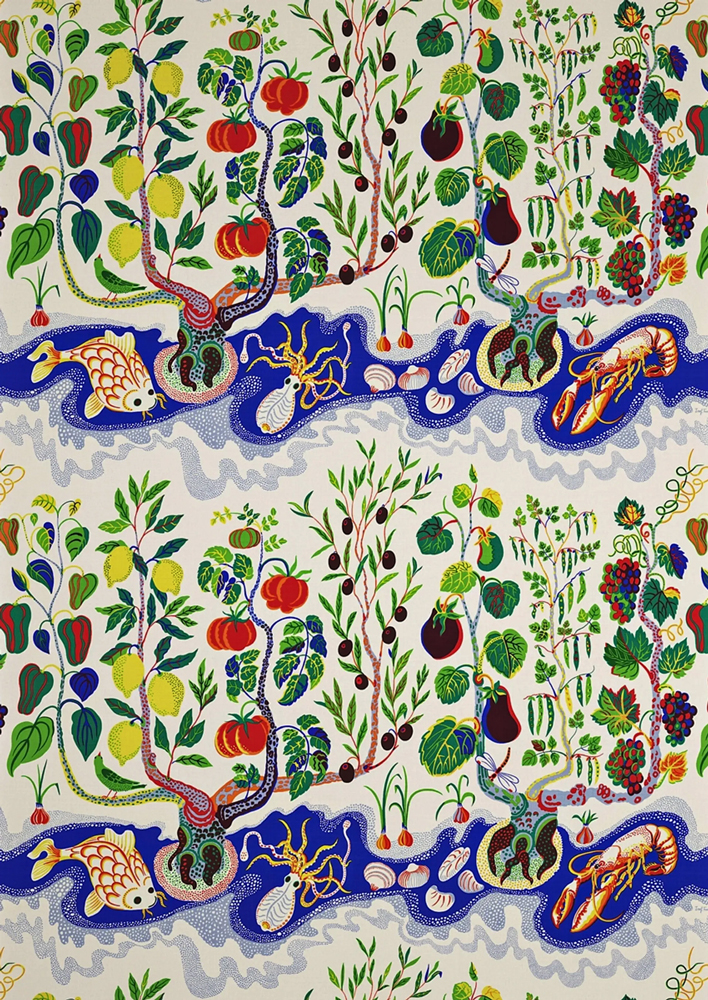

Today, Josef Frank is most associated with his iconic nature-inspired fabrics and wallpapers, but this narrow focus overlooks his immense contributions as an architect and intellectual.

Born in 1885 in the spa town of Baden bei Wien to a Hungarian-Jewish family, Frank was a student of Carl König and studied architecture at the Technische Hochschule and TU Wien between 1903 and 1908. Early in his career, he was drawn to progressive circles where design and intellectual discussion were deeply intertwined. In 1913, he began collaborating with Oskar Wlach and Oskar Strnad, leading to the establishment of the Wiener Schule der Architektur.

After World War I, Frank became a leading figure for the Austrian Association for Settlement and Small Gardening (Verband für Siedlungs und Kleingartenwesen), where he experimented with both architecture and furniture design. From 1919 to 1925, he served as Professor of Building Design at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule). Simultaneously, he was similarly influential in the Neuer Wiener Wohnen, a group of designers and architects pioneering a new approach to furniture and interior design.

“The house is not a machine to live in. It is rather a shell that should include everything human.”

In 1925, Frank co-founded the furnishing company Haus und Garten with Oskar Wlach and Walther Sobotka. This venture connected him with international designers, including the highly respected Estrid Ericson, owner of Svenskt Tenn, a renowned Scandinavian interior design company. Frank, whose wife Anna Sebenius was Swedish, had already developed an affinity for Sweden, spending several summers in the ‘Swedish Riviera’ town of Falsterbo. This connection led him to receive commissions to design five villas in the area between 1924 and 1936.

Italian Dinner Fabric, Josef Frank Credit: Svenskt Tenn

Josef Frank fabric currently at the MAK Wien

As Frank’s international career flourished, he became a well-known character in the Wiener Moderne movement. Oskar Wlach and Josef Frank were the only Austrian architects invited to participate in the 1927 Stuttgart Werkbund Estate, Josef Frank later became the artistic director of the Vienna Werkbund Estate. During this period, he also developed his Raumplan theories.

Among Frank’s significant commissions with Wlach was Haus Beer, a modernist villa completed in 1930 for Dr. Julius Beer in Vienna’s Hietzing district. The Franks and the Beers were close friends, and Dr. Beer wanted a house designed for entertaining and hosting cultural soirées. Today the house is the subject of a major renovation.

In 1928, Frank was invited to Switzerland as a founding member of the International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM). Although now recognized as a Modernist architect, Frank was sometimes critical of the increasing prescription of what was and wasn’t Modernist design, famously stating,

“Modernism is that which gives us complete freedom.”

It’s hard to know if in 1932 Frank was preparing his exit plan but anti-Semitism, always endemic in the Empire, was only growing. The Anschluss would not be for another six years, but in 1932, he signed a formal agreement with Estrid Ericson of Svenskt Tenn. Together, they became a powerhouse. Frank’s textile designs jumped off the page, his lifelong interest in botany brought together in a riot of colours, and his furniture was both modern and highly desirable—to this day! Josef Frank’s brand of modernism was underpinned by his desire to shake off dyed-in-the-wool rigid traditions and give breathing space for personal expression.

“Every human needs a certain freedom of movement within his environment. Too much order creates discomfort.”

With Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, Frank recognized the growing danger and permanently relocated to Sweden in 1934, accepting Ericson’s invitation to work there—a move that will have saved his life. He never returned to work in Austria.

Frank’s work with Svenskt Tenn began with representing the company at an exhibition at Liljevalchs Konsthall, where he introduced the “Liljevalchs Sofa,” a design that defied contemporary Scandinavian conventions. The sofa was a tremendous success, marking the start of a fruitful collaboration between Frank and Ericson. They exhibited together at the 1937 World Exposition in Paris and the 1939 World’s Fair in New York, where their work was closely associated with “Swedish Modernism.” Frank became a Swedish citizen in 1939 by then, he had already established himself as an important figure in the Swedish Modernist movement.

It’s a common question considering the extent to which Modernism emerged and developed in Germany and Central Europe, what would have happened if the Nazis hadn’t taken power and aged war and committed mass murde? With their love of monumental classicism, their irrational loathing of modernism, which they considered immoral and tainted with Jewish and Bolshevik influences, and their brutal suppression of modernist architects and artists, Modernism was stopped in its tracks in Germany and every country they occupied. Institutions were shut down, educators removed from posts, and Jewish architects (a significant number of whom amongst the modernists were Jewish) had their professional licenses to practice removed and if they weren’t able to escape and many were not, they and their families were murdered. For non-Jewish architects, allowed to stay, it became clear immediately that they would must abandon modernism. But modernism did not disappear; quite the contrary, exiled architects took their ideas abroad, where they flourished.

During World War II, deeply concerned about the conflict’s trajectory, Frank moved to New York. Before leaving, he gave Estrid Ericson a parting gift of 50 prints, which the company’s website describes as a significant contribution to design, even surpassing the work of his role model, William Morris.

Josef Frank died in 1967, leaving behind a rich and enduring legacy in architecture and design.

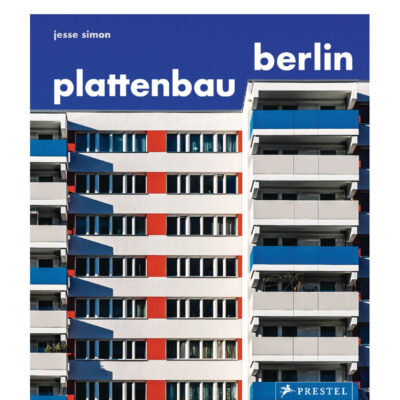

Winarskyhof Wien 20, Josef Hoffmann, Josef Frank, Peter Behrens, Oskar Wlach and Oskar Strnad named for Social Democratic Workers Party politician, Leopold Winarsky

Josef Hoffmann

The Moravian-born Austrian architect and designer, the son of a middle-class textile manufacturer, became a leading light in the Vienna Secession and Wiener Werkstätte. He is known for using traditional craftsmanship with a strong modernist aesthetic, frequently using geometric forms. In essence he could turn his hand to everything from furniture to art to everyday household objects.

Hoffmann had tried to make a Faustian Pact but it seems that the Devil wasn’t that interested.

In 1892, he became a student of Architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts, working on the Ringstaße project to create the Ring Road in Vienna under Baron Carl Freiherr von Hasenauer. In his third year, he became a student of Otto Wagner, which was pivotal to Hoffmann’s development. Wagner’s ideas entirely chimed with Hoffmann’s views.

“only that which is practical can be beautiful“

Wagner 1896 Modern Architecture

Hoffmann was a founding member of the Vienna Secession (1897), and his contribution there, along with his work with the Wiener Werkstätte (1903), perfectly illustrates their impact. His co-founders at the Wiener Werkstätte were Koloman Moser and the Austrian Jewish industrialist Fritz Waerndorfer (who left the project in 1913 when he was declared bankrupt). More than a cooperative of artists, designers and craftsmen, it was an art movement underpinning modernism’s development. Its creators were given artistic freedom, and their work straddled many disciplines, from architecture to furniture design, textiles, ceramics and jewellery. The Wiener Werkstätte used traditional crafts but wasn’t opposed to employing modern manufacturing methods, whichever best fitted the purpose but it didn’t favour mass production. Philosophically members saw it all as part of their gesamtkunstwerk, the creation of a ‘total work of art’

“…We want to encourage close contact between the public, the designers, and the craftspeople and produce good-quality, simple household utensils. We begin with the purpose, serviceability is or first requirement. Our strength should lie in good conditions and good treatment of materials. Where possible, we will aim to decorate but without compulsion and not at any price ….”

(from the work programme of the Wiener Werkstätte, 1905 via MAK)

Josef Hoffmann Wiener Werkstate: Embossed leather Leather book cover for Walter von der Vogelweide poems Munich 1920 MAK Wien.

Josef Hoffmann became a Professor at the School of Arts and Crafts in 1900. He was organised, prolific, and had a clear vision, much of which he realised, a point to return to later.

The Wiener Werkstätte’s grandest commission was the Palais Stoclet in Brussels (1911), a private home for banker and art collector Adolphe Stoclet. Koloman Moser and Gustav Klimt played significant roles in this project. Klimt designed seven-metre-long friezes – they saw the project as the perfect vehicle to create gesamtkunstwerk. Stoclet was so enamoured of the creation that he asked to be buried with a ‘black and white handkerchief by Hoffmann.’

Josef Hoffman, hand cut crystal and sheet steel chandelier 1914

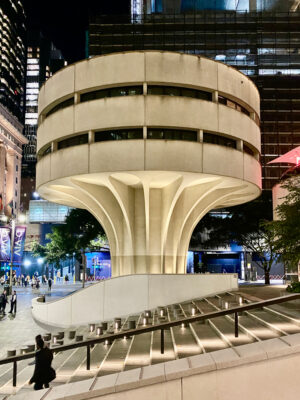

Another early Wiener Werkstätte architectural commission was the Sanatorium Purkersdorf on the outskirts of Vienna (1905); it was for this health spa that Hoffmann designed his ‘sitzmaschine’ – literally a machine for sitting. And let’s not forget the iconic Kubus chair (1905) still in production today, Villa Ast, Cafe Fledermaus and the Austrian Pavilion at the 1934 Venice Biennale.

Sanatorium Purkersdorf Image Roman Klementschitz CC BY SA 3.0

Purkersdorf Sanitorium Entrance Hall Image Thomas Ledl CC BY SA 3.0

While it would be nice to ponder the legacy of Hoffmann’s enormous contribution to modernism, it isn’t possible to ignore his choices after 1938 when he was already 68 and might have avoided the obloquy he has attracted by simply retiring. He didn’t retire, instead recognising that he was the beneficiary of the collapse of most Viennese modernist architects’ practices and their persecution—let’s not forget he knew many of them well, had been taught alongside and worked with them. Also, remember that many of his contemporaries who didn’t need to flee because they weren’t Jews nonetheless left Austria. Josef Hoffmann stayed. But Hoffmann was a Modernist, synonymous with the movement, and that was a problem because to the Nazis and their lickspittles Modernism was degenerate, and he wasn’t able to just drop the design movement that had made his career. Hoffmann was at least well-connected with people in Vienna’s administration, which enabled him to pick up municipal contracts. An early one was the commission to design the Haus der Wehrmacht, turning the historic German Embassy into an officers’ club for the Wehrmacht, the German armed forces. Hoffmann embraced the project, creating all the furniture and even specially customised swastikas.

MAK (the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna) comments,

‘Josef Hoffmann used and cultivated his connections in a time of social upheaval. He neither took up the cudgels for old friends nor questioned the new regime. He rather tried to entirely adapt to it to be able to continue working as an artist, however, the National Socialists never really trusted Hoffmann and the relationship remained ambivalent’.

The enormously powerful and influential Albert Speer ,Hitler’s favourite architect and hisMinister of Armaments and War Production, was also an obstacle to Hoffman’s ambitions as he was said to dislike the ‘Viennese style’.

Awkward is the word that springs to mind – here was Hoffmann, trying to ingratiate himself with the Nazi authorities,for example, his vase with the coat of arms of the State of Saxony and swastika currently part of the collection of the Wien Museum, relishing every commission he got but never fully embraced by the Nazis.