Thoughts from a Corbusian Completist

Unité d’Habitation Marseille ©

What do you do when you realise that you’ve ‘got stuck, like a record stylus in a groove, and can’t stop talking about Le Corbusier’? Two novels later Colin Bisset had figured it out, Loving Le Corbusier throws the spotlight on fashion model, Yvonne Gallis, Corbusier’s outspoken wife who, unlike the sophisticated Corbu, came from a working-class Mediterranean family. Clearly a match of equally strong characters, Yvonne is said to have banned ‘Doudou’ from discussing architecture at the dinner table.

Corbusier 1964 Image Joop Van Bilsen

Colin, who today lives in Sydney, was born in England and studied History of Art specialising in modern architecture at the University of East Anglia (home to Denis Lasdun’s brutalist ziggurats). After a stint as an interior designer in London, he moved to Australia where you can hear his broadcasts about design on ABC Radio National and catch his Blueprint for Living podcast. Need Feng Shui advice? He’s your man.

Greyscape caught up with Colin, encouraging him to share his obsession, which, btw, we totally get and equally obsess about. ‘I was being interviewed on the radio about which buildings to visit when overseas. I’d mentioned how listeners should visit Corbusier’s modernist worker’s estate at Pessac, the Quartiers Modernes Frugès, and that no outing to Marseille was complete without a visit to (or preferably a stay at) his Unité d’Habitation there.

Nantes Reze Béton Staircase ©

The same went for the one at Rezé, outside Nantes. The radio interviewer interrupted. “So you’re a completist,” he said with a hint of exasperation. I fell silent at last. I was sprung. A Corbusian completist, yes. A Corbusian tragic, most definitely.’

Nantes-Reze Unité d’Habitation ©

I have loved Le Corbusier’s work since I first studied it at university in England but it’s only fairly recently that I’ve begun to visit so many of his buildings. In 2013, I decided to write a novel based on the life of Yvonne Gallis, the wife of Le Corbusier. Theirs was a sometimes turbulent but always loving relationship, and I had wanted to explore what Charles-Edouard – or Doudou, as she called him – was like away from work. Was he as austere and arrogant as many people portrayed him? As part of my research, I needed to submerge myself in his buildings. However well you think you know a building, nothing beats actually visiting it.

Firminy Pilotis ©

‘Architecture is not only a three-dimensional experience but a five senses experience’

In Marseille, I needed to smell the hot Mediterranean air from the Unite d’Habitation’s rooftop, feel the sun on its concrete flanks, hear the sound of its squeaky lino-floored corridors, taste the dust of its years, and see how well its massive form sat on the Boulevard Michelet (askew, to ensure that all the apartments receive as much sunlight as possible).

I had been inside one of the Unité’s apartments before, only that was the full-scale model meticulously recreated by design students at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine in Paris. Stepping into a real apartment one morning in Marseille was a familiar experience, yet different. Whereas the Paris recreation is perfectly kitted out in state-of-the-moment furnishings, the Marseille apartment was a functioning home. Its kitchen still had Charlotte Perriand’s clever arrangement of sliding cupboards and the sloping surface of knobs above the benchtop on which pans and their lids can be easily hooked. The sliding panel between the two children’s bedrooms was still in use, only this blackboard was scrawled with an adolescent’s messages, the equivalent of ‘This is my space – stay out!’

Le Corbusier’s first commissions after the Second World War

It’s hard not to overuse the word masterful when you describe the living spaces of the Unité at Marseille. It was one of Le Corbusier’s first commissions after the Second World War, which had seen much of central Marseille flattened. There was a desperate need for housing and Le Corbusier was the man. He had been writing about apartment living since the early 1920s when his notorious plan to raze the Marais district of Paris and replace it with tall towers shocked the world (and is still used as ammunition against him by those who don’t quite get what he was doing). Now he had the opportunity to show whether or not he could pull it off. He agreed on the proviso that the building needn’t comply with local planning laws.

Marseille Unite d’Habitation Corbusier and Nadir Afonso ©

“Une maison est une machine-à-habiter” A house is a machine for living in. Corbusier Towards an Architecture 1923

Which is why the building, as huge as a stranded ocean liner, is slanted away from the busy street and set so sumptuously in its parkland of trees. No wonder the locals called it the Maison de fada, the madhouse or looney bin. But that was water off a duck’s back for Le Corbusier, who had weathered similar slurs at Pessac, which locals called the Arab village because of its flat roofs (and not meaning to be complimentary).

Marseille Cité Radieuse Unité d’Habitation Shops ©

Marseilles’ Unité was the first to be completed, opening in 1952. Others would follow. Each would be different. Marseilles’ prefabricated apartments were slotted into a frame, like bottles in a wine rack, ensuring airspace around each apartment which gives sound insulation and allows heating and air ventilation throughout the whole building. His next, at Rezé, was different. Built to house workers at the docks on the Loire river nearby. Funds were tight and these apartment units were stacked like boxes, which meant that people could move in before the whole structure was completed.

Reze Unité d’Habitation Concrete detail ©

It lacks the swagger of the Marseille building – its piloti are thinner, although submerged at one end in a frog-filled pond left after the site was quarried. Where Marseilles’ rooftop walking track and exuberant ventilation stacks have a sculptural quality, the roof of Rezé is quieter, occupied by an infant school. The concrete walls of the building are also covered with a kind of pebbledash, giving it a more sombre air and less like the sunbleached quality present in Marseille. Its balconies are painted in duller tones than the bold primaries at Marseille, more suited to the flatter northern light. But it’s still a marvel, filled with detail that excites and amuses, like the giraffe-shaped staircase that springs out of one end.

Nantes Reze Unite d’Habitation ©

Most recently, I visited the Unité at Firminy. This was the last built, completed in 1967, two years after the architect’s death (the other two are at Briey-en-Forêt and in Berlin, where stricter planning laws meant less floorplan flexibility).

Firminy is a working town, just outside industrial St Etienne not far from Lyon. The Mayor, Eugène Claudius-Petit, was a very old friend of Le Corbusier. He actively promoted the architect’s ideas and designs.

Firminy Vert Unité d’Habitation ©

The focus is on a playing field with a generous sports stand. Overlooking it is a cultural centre which has the same colourful ventilation doors as in the Couvent de la Tourette. Hidden amongst more mundane housing blocks is the Unité building. It crests a hill but once there, it takes away your breath.

Firminy Unité d’Habitation Modulor

It simply uses only the colours red and blue on its balconies and its broad facade is both welcoming and proud. The closed-off roof terrace lacks the embellishments of Marseille but the internal ‘streets’ are familiar and as colourful as those in Rezé and Marseilles. Embedded in the concrete walls are the shapes of Modulor Man and stylised plant forms. A display apartment shows the same dual-level living that is familiar to anyone who has visited the mock-up in Paris. The sense of a steady hand is ever-present.

Unité d’habitation of Nantes-Rezé ©

Marseille’s Unité is hipster heaven. A resident who has lived there for years told me it was now less communally-minded. The fizzing energy of the complex still struck me. I am more struck, however, by the cheerfulness of the residents at the buildings at Rezé and Firminy. One gives me the thumbs up as I take my many photographs. The caretaker at Rezé tells me how proud he is to live there. That a building can add dignity and pleasure to the lives of people is surely the best outcome for all housing design. And dare I venture that it’s the final proof that these buildings are the work of an undoubted master. But maybe I should save that until I’ve ticked the last two off my list’.

Greyscape Needs To Know Before You Go

What’s your ‘must take’ items when you travel?

If I don’t have a notebook with me then I record my thoughts on my Samsung and write them up later. It’s great if you can return to buildings at different times so that you see them in a different light.

Photos – what are you using ie phone, camera etc – any tips for others?

I use a Samsung Galaxy 9+ for my photos and videos. The quality of the camera is clearly better than my old cameras and camcorders. And, it means I’ve got less to lug around. Taking a notebook is essential for me. I can write down whatever strikes me about a building when I am there – often it’s the tiny details that tell you most about the place, like a door handle or the depth of a window sill. I always think it’s good to get down what I’m feeling when I see a building because a building that moves you is such a wonderful thing.

Visiting Ronchamp was a very emotional experience, as was La Tourette, but I didn’t feel anything except curiosity when I visited the Heidi Weber Museum in Zurich recently

Colin’s favourite films:

The Godfather – the gloomy interiors, the family dynamics, the sense of place (New York and Sicily), Nino Rota’s fabulous score. Godfather 2 is even better and I Am Love – Tilda Swinton in anything is great. This film is so coolly elegant and so beautifully acted. More family dynamics! The Milan scenes are horribly claustrophobic but then there’s the contrast of nature and sunlight in Liguria. Great music, too, by John Adams.

Fav Album:

Being Boring by the Pet Shop Boys – moves me every time and makes me think of my hilarious best friend Glyn who died when we were young.

Book:

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck – the hope and hopelessness of people seeking a better life, still pertinent.

Read Colin’s blog www.colinbisset.com

Find Colin on Instagram www.Instagram.com/colinbisset88/

Loving Le Corbusier is available through Amazon, Bookbaby and iBooks

All images (save for image of Corbusier) Copyright of Colin Bisset

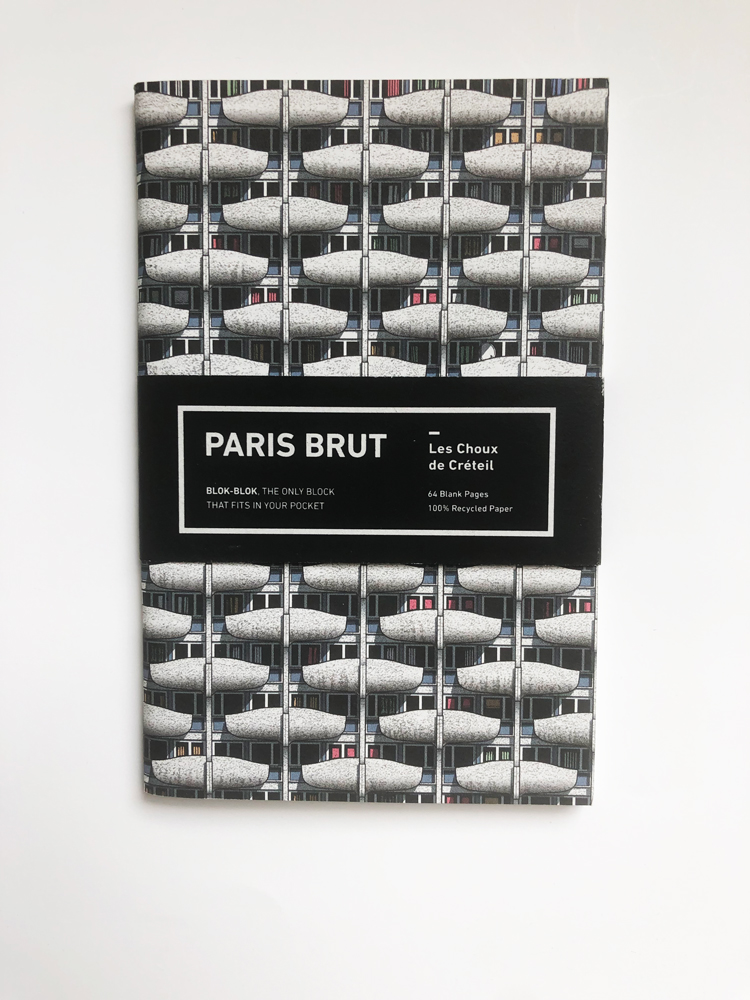

GREYSCAPE LOVES

Paris Brut Notebook £6.50