The Inspiring Fight On The Ground To Save Berlin’s At-Risk Brutalism

Campaigners have finally won the fight to save the Mäusebunker and the Hygieneinstitut. It took the powers of Mighty Mouse to truly protect two of Berlin’s most treasured and most at-risk Brutalist buildings.

Mäusebunker Image Gunnar Klack ©

Here we tell the story of determined, motivated people, a story familiar to campaigners trying to preserve iconic buildings but before we do, let’s celebrate that this particular success has met with success. On May 24 2023 the German Department of Heritage Protection announced that the Mäusbunker has been designated a historical monument and is saved from destruction. The Hygieneinstitut was listed in 2021 and has also been saved.

Our story begins with Architect, Gunnar Klack and Architecture Historian, Felix Tokar.

They never visualized how their shared love of Brutalist architecture would trigger a national campaign but, the combination of politics and a lack of cultural appreciation for architecture and an aversion to confronting tricky topics has revealed some deeply held sensitivities in Germany. Two buildings, known fondly as the Mausebunker and the Hygieneinstitut, the Institut für Hygiene und Umweltmedizin der Charité and the Forschungseinrichtung für experimentelle Medizin der Charité, are part of the Free University Berlin.

Hygieneinstitut Image Gunnar Klack ©

Gunnar Klack explained;

‘The Mäusebunker and the Hygieneinstitut are spectacular examples of how late Modernism developed from International Style in different directions. They form part of the Benjamin Franklin campus within the Charité Hospital complex. The artefacts at risk are not only one of a kind in their architectural aesthetics, they are also witness to Berlin’s unique history as a divided city during the times of the Cold War.’

Embedded in the story, according to Gunnar, ‘is a political scepticism towards historic preservation by Berlin politicians, especially when the artefacts in question are controversial, high-maintenance or expensive.’ Locally, questions remain around what to do about large buildings from the ‘70s, which might explain why the buildings were not listed. Therefore the Charité – an influential Berlin medical science institution that intends to redevelop the land into a new research campus – did not have to seek approval for destroying the buildings.

Mäusebunker Architects: Gerd Hänska, Kurt Schmersow, 1967–1981 Image Gunnar Klack ©

Berlin in the ‘60s and ‘70s made huge investments into scientific institutions to duplicate infrastructure that was locked away on the other side of the Wall. More than just the provision of needed medical centres, these institutions fought a proxy battle for the reputations of the rival blocs.

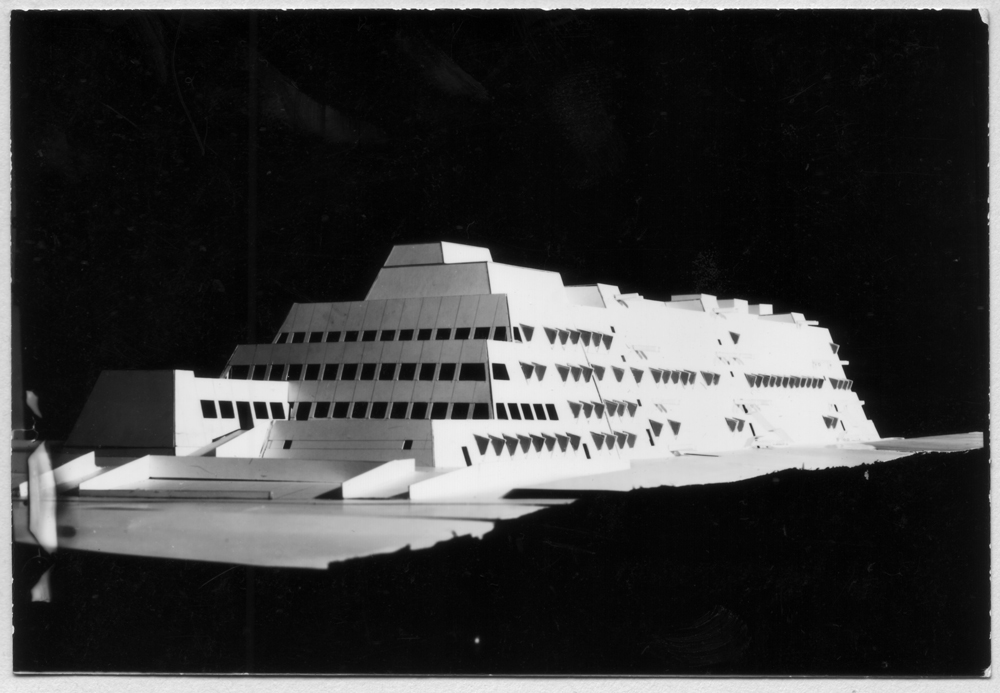

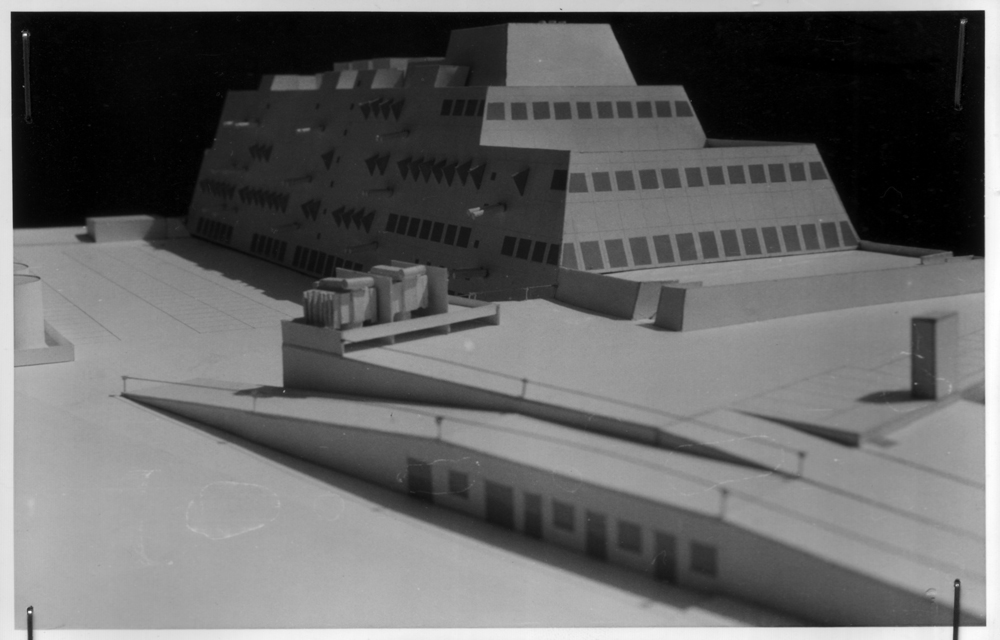

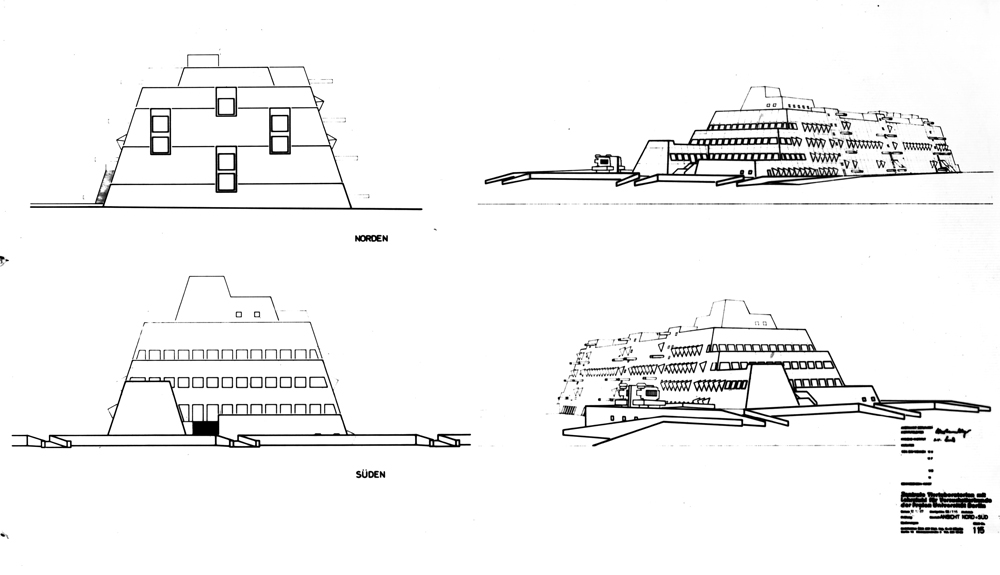

Original Models Image Gerd Hänska / CC BY-SA 4.o

Charité

The 300-year history of Charité may include the half of German Nobel Prize winners, but also a contentious history during the Nazi regime. The recent Netflix drama, Charité at War, reveals the dilemmas and compromises of operating a hospital under Nazism. A close inspection of the truth shows Charité was not guiltless during this period. By destroying the building, Berlin’s government is able to raze unflattering history.

‘I discovered that the evaluator, made the choice to not recommend the building for conservation,’ explain Klack, ‘In the years following 2009, the State Office for Cultural Heritage had other projects on their agenda, so nobody took a close look at Hygieneinstitut or Mäusebunker again. I do not know if Mäusebunker was also evaluated negatively back then in 2009. Regardless, the results are the same so far, neither building is listed.’

By Gerd Hänska – Nachlass des Architekten, CC BY-SA 4.0

In 2015 Gunnar met Oliver Elser, curator of the Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) in Frankfurt am Main, and Felix Torkar. Out of their shared passion for Brutalist architecture came their creation of Initiativgruppe M. Elser was working on the now renowned Berlin exhibition SOS Brutalism. Felix who worked at DAM was in the process of compiling a worldwide comprehensive map of Brutalism. A chance conversation with its facility management revealed to Gunnar that Charité’s aim was to get rid of the buildings. They asked that the information not be shared. When Gunnar subsequently spoke at a conference about the Mäusebunker the debate turned to cultural heritage making him the go-to person on the topic. By last summer Felix and Gunnar had become expert speakers on the circuit about Mäusebunker.

In January 2020, Gunnar learnt from Ludwig Heimbach, the Bund Deutscher Architekten (Association of German Architects), how shocked he had been to discover that neither building was listed as a cultural heritage site. Shocking, but there was still a chance the buildings could be saved and Charité, as a state institution had, in theory, to act in the public interest. Yet was there the political will to act when through accident or design the buildings hadn’t been protected? The head of Berlin’s State Office for Cultural Heritage Management said that his office was now carefully deciding what to do.

Mäusebunker Architects: Gerd Hänska, Kurt Schmersow, 1967–1981, Krahmerstraße, Berlin-Lichterfelde Image Gunnar Klack ©

Newly invigorated Felix and Gunnar launched a campaign to save both buildings. It went viral. It drew support from local activists, enthusiasts and newspapers and a widely circulated open letter by Kristin Feireiss and Professor Adrian von Buttlar, a highly respected architectural curator and professor of art, respectively, brought powerful academic support to the campaign.

The team took two lines of attack; Felix and Gunnar started a petition and Ludwig Heimbach started preparing an exhibition for Bund Deutscher Architekten. The petition website received so much support it was quickly overwhelmed and it’s been moved here and, importantly, the press picked up the story.

Hygieneinstitut Berlin Image Howard Morris ©

Hygieneinstitut Image Gunnar Klack ©

Gunnar believes that the campaign cut through the noise because Mäusebunker is universally appreciated among architects and appreciated for Brutalism is a global phenomenon. He also notes that it is more sustainable to renew existing structures than demolish and construct new. Plus, one can’t overlook the historic value in Mäusebunker.

There was a breakthrough on April the 21st when Charité made a public statement to confirm it had changed its mind and wouldn’t demolish the Hygieneinstitut and that it was planning to invite architects to a brainstorming workshop to develop ideas for the Mäusebunker.

Hygieneinstitut Berlin Image Howard Morris ©

Hygieneinstitut Image Gunnar Klack ©

Charité agreed to refrain from destroying the Hygieneinstitut but remained committed to their plans to extensively remodel the building. This prompted Gunnar and Felix to keep a close eye on the proposed time schedule. The original intention was to begin to empty out the Mäusebunker tin July 2020, with a demolition date scheduled for the Autumn.

‘Its unlisted status means that given a free rein, Charité can make major changes which will destroy the buildings original character. Whilst the shell might be saved, its authenticity probably will be lost.’

The fight went on and now the Mäusbunker and the Hygieneinstitut are saved. Felix tells Greyscape:

‘After three years and 10,683 signatures [to the petition]it happened: Both the Hygieneinstitut and the Mäusbunker were registered as cultural monument of the State of Berlin!

It is a moment to celebrate and also a moment full of humble gratitude. Without the great deal of support and participation of so many people this success would certainly not have been possible. We sincerely thank you all.’

Successful campaigning exacts a price in time, effort and participation. Campaigners for saving heritage buildings aren’t chasing commercial goals, they give up a lot and need many others to come alongside and support them. Sadly there have been many campaigns to save buildings that have been unsuccessful and once our built heritage is reduced to dusty rubble, it’s gone. We salute the volunteers who have achieved this success, many it be an inspiration.

See The Campaign

Twitter: https://twitter.com/maeusebunker

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/maeusebunker/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/maeusebunker/

Gunnar on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/gnrklk/

Felix on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/flxtrkr/

Location

Krahmerstraße, Berlin-Lichterfelde

Image Gunnar Klack ©

Image Gunnar Clack ©