Siedlungen der Berliner Moderne

Maybe it’s the Bauhaus at the front of our minds that’s crowding out thoughts of one of Berlin’s most creative Weimar Republic endeavours to improve the living conditions of the city’s residents. The ‘Siedlungen der Berliner Moderne’ six modernist housing settlements were designed as an alternative to the tenements that working-class Berliners were typically living in. The project was led by Bruno Taut and Martin Wagner with Walter Gropius, Hugo Häring, Hans Scharoun and landscape architects Ludwig Lesser and Leberecht Migge playing an important role.

Image Lucienne Cole ©

Today we would not hesitate to expect that every family housed in low-income social housing has their own kitchen, bathroom and electricity, however, this was not then the norm, the architects’ inclusion of these basics was seen as groundbreaking. But this was not without critics who questioned the necessity.

Bruno Taut’s influence and interest in the building of the settlements cannot be underestimated. The project spoke to his and Urban Development Councillor, Martin Wagners’ political leanings and came at a time of growing interest in the Garden City Movement. Taut was a towering local figure, if he were represented by a thread, woven into a tapestry representing architects who grew to international prominence out of tatters of WW1, then his skein would weave through every stitch.

Berlin Modernism Housing Estates

It’s hard to explain why the Berlin Modernism Housing Estates are not widely discussed outside architecture and design circles, however, they genuinely deserve more attention from visitors to Berlin. It has taken UNESCO a long time to give them their well-deserved World Heritage Site status. Awarded in 2008, it cited ‘These Berlin settlements are extraordinary examples of the housing developments built during the early decades of the 20th century and were models for housing and living in the big cities of the modern industrial society. These not only facilitated the provision of healthy flats with attractive amenities but also offered a basis for new forms of housing and living. These housing estates were designed with community facilities offering an exemplary social and service infrastructure and a wide range of communal functional and event spaces, spanning models like the experiment of a cooperative-based community, Taut’s “outdoor living space” and Scharoun‘s concept of “neighbourhood”.’

Image Lucienne Cole ©

Tracking back; the development of The Garden City Movement was not solely a German idea, the notion of a new style of urban planning was embraced in many cities across the world. In England in1898, Sir Ebenezer Howard wrote To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, in which he dreamed of a self-sufficient planned space with parks and boulevards all forming part of a group of similar spaces. A year later he founded the Garden City Association to help turn his dream into a reality. In Tel Aviv, a quarter of a century later, Scottish architect Sir Patrick Geddes presented his 62-page Geddes Plan, paving the way for today’s UNESCO recognized ‘White City’.

Deutsche Gartenstadtgesellschaft

The German Garden City Society, the Deutsche Gartenstadtgesellschaft saw the coming together of the best architects and Landscape architects looking to address the traumatic devastation wrought by WW1 as an opportunity to re-imagine the human landscape. They sought a way to alter the accepted status quo that saw a divide between the haves and the have-nots. There were differences in interpretation, some saw the movement as a means to encourage a healthier environment within the confines of limited space, others as a way of addressing the needs of increasingly mechanized society. What was clear was that these settlements, on rural land outside the centre of the city, offered an alternative to overcrowded poorly designed city accommodation currently on offer, here were homes with meaningful green outside spaces incorporated into the design, Außenwohnräume. This was the next step for a fast expanding Berlin that had been the subject of James Hobrecht’s 1862 master plan for the city. The settlement plan was greatly boosted by the trades unions’ and cooperatives support for the project.

Image Lucienne Cole ©

Bruno Taut’s pioneering use of colour in modern architecture makes the Gartenstadt Falkenberg, the Falkenberg Garden City, a series of single family houses known collectively as the ‘Paintbox Estate’ (Tuschkastensiedlung) all the more striking, and alluring to photograph. It was the first estate to be completed in 1916. It should be noted that the seeds of the idea were sown earlier by Heinrich Tessenow, however, the bold design is completely Taut’s hand at work. Not everyone approved of its design, perhaps it’s an urban myth, but Corbusier is said to have commented

“My God, Taut is colour blind.”

Artist, Lucienne Cole, spent a year’s art residency in Berlin and her photos capture the allure of Taut’s modernist settlements. She shares, ‘Part of my reasons for my residency in Berlin was that it enabled me to visit Dessau and to see a specific Schlemmer exhibition and to visit Magdeburg to see an exhibition about the lesser-known artist Xanti Shawinsky who was heavily involved in the Bauhaus stage. I have always had a thing about Paul Klee from an early age and his ideas about colour and rhythm and his melancholy has always been in the back of my mind, I suppose. She notes about Klee’s house, ‘I was particularly struck by the colour scheme he chose for the interior of the house he lived in’

Carl Legien, Bruno Taut Estate

Lucienne’s mentioned that on one of her visits to the Carl Legien, Bruno Taut estate she was greeted at first with an element of suspicion by a tenant as to why she was taking photographs of their home and they were then surprised that someone would be interested in it which adds a layer of thinking about what creates an ideal community space. Can an estate accidentally become closed to the visitor and frankly does it matter? What would Taut have visualised? What happens when a place suddenly becomes an object of interest to photographers – are there lines that should not be crossed in terms of invasions of privacy. Photograph a house from across the road – okay? Into a window, not okay? Where is the line drawn?

Image Marbot CC BY SA 3.0de

Image Lucienne Cole ©

Lucienne’s time in Berlin led to her developing a fascinating blog which is now something of a love letter to the city. Her practice remains rooted in popular culture., It encompasses Performance, Video, Photography, Print and Collage and is a place where the slippages between fantasy and reality in everyday life are documented. She has become particularly interested in colour, pattern and movement and their relationship with music’.

Favourite Artist?

‘It’s hard to choose. There are people/works that stay with you forever, it’s like that with records too. You dip between. There are points where some things become more pertinent or relevant at a certain time. So I’ve gone with the two that have been in my minds-eye for what about the last 10 years maybe and are very relevant right now’.

‘I can’t remember how I got to Sonia Delaunay, or rather how I got more into her. I’ve always been interested in pattern and fashion history. However, with Sonia, it is more than that. She had such a huge output and must have had a tremendous work ethic and joie de vivre. Sonia and her work are so entwined. She captures the notion of a complete artwork- or ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ *– which is also a Bauhaus concept, and particularly an Oskar Schlemmer concept. It is from where I draw my connections. Bauhaus believed that creative skills could be developed by making connections between different forms of sensory expression and embraced the process of creating and the importance of play.

*A Gesamtkunstwerk is a work of art that makes use of all or many art forms or strives to do so”

Where does the DJing fit in?

‘Dance/ Movement and Music are pivotal to my being and to my art practice – Music is universal. I started dancing at an amateur ‘church hall’ level when I was three. I was brought up in a house with my Dad’s Jazz records. My elder sister constantly playing Bowie and the Rolling Stones. Bowie is a constant in my life as is Soul music. I co-run a Northern Soul night in London. It’s now coming up to its 9th year which has become like a second family.

I started Djing in Liverpool where I was at Art School. I created a club night called ’boutique’. The concept I had was for it to be a bit like going over to your mates when their parents were out. Raiding the drinks cabin and dancing in the front room to your folks and your older sisters record collection! It was also around the time of the easy listening thing that was happening in London and the influence of the London club Smashing.

I got more into Northern Soul from living up north and meeting an old mate of my ex-boyfriend in Manchester. It started with buying records and djing. My first introduction did happen earlier when my Mum took me to the opening of Tower Records. With my record voucher in hand, a gift from my aunty, I bought a Kent record compilation. It was the picture on the front of The Flamingo Club and reading through the liner notes on the back that had me hooked.

We needed to know more about the club night!

‘It’s called Crawdaddy, it’s in its 10th year, and is all about Northern Soul, Motown, Ska, R&B & Boogaloo. Check-in on it @crawdaddysoulclub

Favourite Film? Lucienne’s favourite film (okay we had to work our way down from favourite ten): Gregory’s Girl and Funny Face

Favourite Book? What I loved by Siri Hustedt

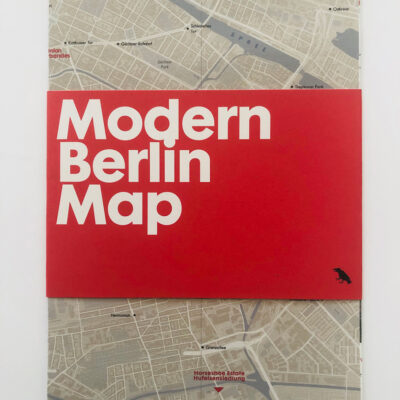

Berlin ‘Hufeisensiedlung’ Horseshoe Estate © A.Savin, Wikimedia Commons

Stuff you need to know if you are prepping a visit to the settlements:

Click here for geo-tagged locations of the estates on our satellite image maps

Gartenstadt Falkenberg 1913-1916

Architects: Bruno Taut and Heinrich Tessenow Landscape Architect: Ludwig Lesser

Siedlung Schillerpark 1924-1930 Wedding, Mitte, Berlin

Architect: Bruno Taut

Großsiedlung Britz (Hufeisensiedlung) 1925-1930

Architects: Bruno Taut, Martin Wagner Landscape Architects: Leberecht Migge, Ottokar Wagler

Wohnstadt Carl Legien 1928-1930Prenzlauer Berg, Pankow, Berlin

Architects: Bruno Taut, Franz Hilinger

Weiße Stadt 1929-1931 Reinickendorf of Berlin

Architects: Otto Rudolf Salvisberg, Bruno Ahrends, Wilhelm Büning Landscape Architect: Ludwig Lesser Urban Designer: Martin Wagner

Großsiedlung Siemensstadt (Ringsiedlung) 1929-1931 Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, Berlin, and Siemensstadt, Spandau, Berlin, Architects: Hans Scharoun, Walter Gropius, Otto Bartning, Fred Forbat, Hugo Häring, Paul R. Henning Planner: Martin Wagner

It’s often known as the Ring Estate, this is due to the association of all architects and planner with The Ring (excluding Paul R. Henning and Fred Forbat).

Image Fridolin Freudenfelt CC BY SA 4.0

Find Lucienne Cole here on Axis Web

Check out her blog about Carl Leigen estate here

She will be exhibiting in March at SUPERCUTS at ARTHUB, Creekside, Deptford, until the end of March 2019