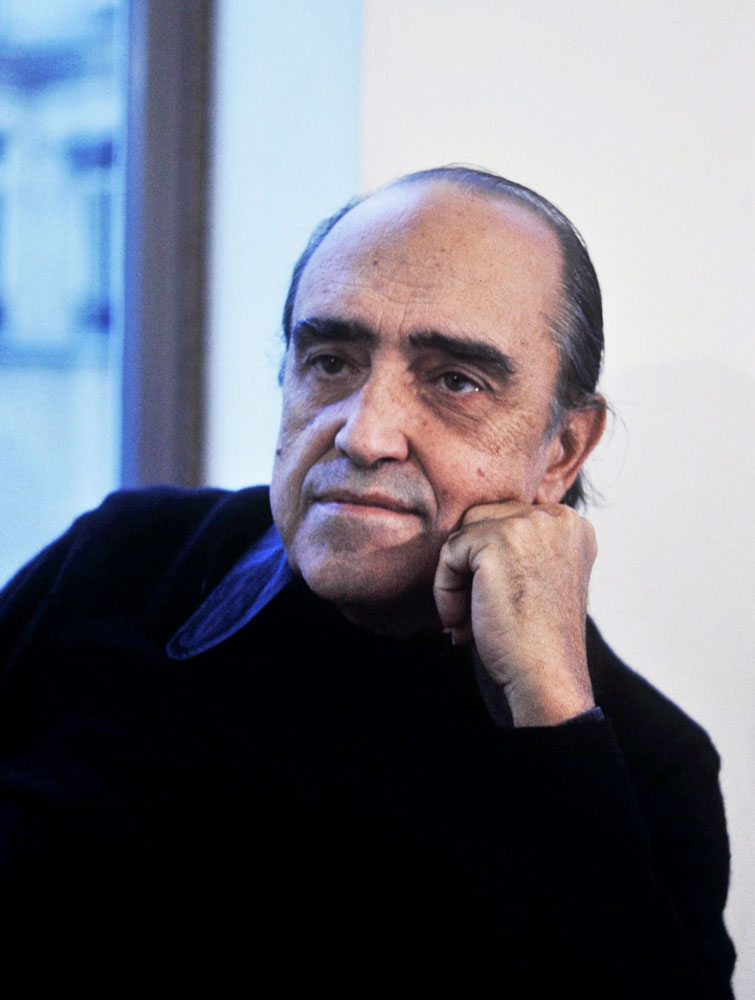

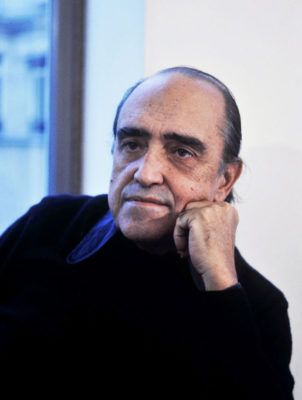

Researcher and fan of modernist architecture, David Torrance, shares why ‘parting is such sweet sorrow’ when it comes to Oscar Niemeyer’s colossal Edificio Copan.

Shaped like the Tilde above the ‘ã’ in São Paulo, netted and unadorned

Rarely have I been so reluctant to leave a building. With an Uber en route to transport me to São Paulo International Airport, I watched the sun rise from the 21st floor of Oscar Niemeyer’s Edificio Copan in the heart of Brazil’s sprawling ‘mega city’. The pinkish skyline was framed between two ledges and filtered through netting which now covers the whole S-shaped structure, added in 2014 to protect pedestrians from the façade’s loose mosaic tiles (it proved too late to save a poodle). The previous evening, I’d lingered over the red-and-orange sunset with a glass of Chilean wine. It was, as my Airbnb host had told me, ‘the best time of the day’.

View across the 21st Floor of Block B

Usually I arrange accommodation after selecting a travel destination, but on this occasion, it was the other way around: I’d read about other Airbnb apartments at Copan (and the spectacular light shows at sunrise and sunset), so reserved a few nights and then looked into flights from Santiago, which I’d arranged to visit almost a year before. Is architectural tourism a thing?

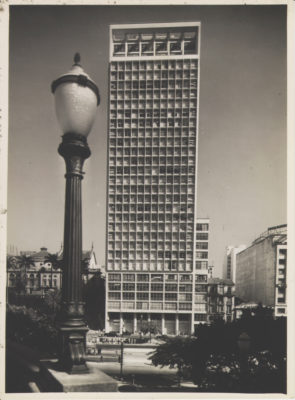

Brazil’s Largest Reinforced Concrete Building

Rooftop View From The 32nd Floor

I immediately loved São Paulo, but Edificio Copan proved a destination in itself, almost a microcosm of everything that city had to offer – a Brazilian Barbican. Construction began in 1952 and, following some interruptions, was completed fourteen years later, then as now one of the largest buildings in Brazil. It contains an astonishing 1,160 apartments over 38 storeys and even has its own postal code, ‘CEP’.

Oscar Niemeyer: Image Roger Pic

Although the building was designed by Niemeyer’s office in São Paulo, the architect was personally responsible for the building’s distinctive ‘S’ shape. The idea (his?) was the creation of an egalitarian edifice available to Paulistas of all shapes and sizes. (The building’s name is an acronym for its original developer, Companhia Pan-Americana de Hotéis e Turismo, Portuguese for ‘Pan-American Hotels and Tourism Company’.)

Six Blocks 1160 Apartments 70 Businesses

Before the protective net was added: Image 2009 Silvio Tanaka CC BY SA 2.0

Copan’s upper levels, as I later discovered, housed three-bedroom family-sized apartments, while others, such as my temporary accommodation, weren’t much larger than hotel rooms. Indeed, ‘Bloco B’ had been intended as a hotel, although financial problems meant its rooms were converted into smaller, more affordable units. It suited me just fine, a large main room with windows covering one side, a small kitchenette and a slightly more generous bathroom.

Not counting transient visitors such as myself, Copan is home to more than 2,000 residents. They are served by 100 employees, 20 elevators and an underground carpark with around 220 spaces (many occupied by vintage Fords). The ground floor, which Niemeyer had intended to be open to people and the elements, now houses more than 70 businesses including a now-dormant evangelical church (formerly a cinema), a travel agency, bookstore and four restaurants.

This lends Copan a community feel, meaning it’s possible not to leave its environs for days on end (a prospect I confess to having found attractive). Other aspects of Niemeyer’s vision were not realised. The original project was predicated on two buildings, the other being a hotel, but only the residential block was completed. A park outside the building was also planned, although that space is now occupied by an unremarkable bank building.

Block B

Whether Niemeyer intended it or not, egalitarianism rules in the daily tradition of allowing residents and tourists to visit Copan’s roof deck at 11.15am and 3.15pm. A pleasingly orderly queue forms at the bottom of Block F. This allows captivating views of São Paulo and a closer look at the building itself, including its transparent blue-black tile-catching drape. A project to repair or replace the building’s 72 million exterior tiles is apparently in the works.

70 businesses on the Ground Floor, a Church and four restaurants

Vintage Residents in the Underground Car Park

Oscar Niemeyer’s most famous commissions are in the contrived federal capital of Brasilia. However São Paulo has its share of the modernist master’s output, from the quirky Latin American Memorial to the sprawling Parque Ibirapuera. The latter encompassing a number of public buildings, museums, art galleries and an astonishing auditorium, connected by sweeping, organic walkways. Nothing, however, proved as satisfying as returning to Copan each evening.

Split Level Apartments

David Torrance is a constitutional specialist at the House of Commons Library. Before that he was a political commentator and author of more than a dozen books on Scottish politics and history. In his spare time he seeks out modernist architecture all over the world

Find David on Instagram at www.instagram.com/davidtorrance1977/

Images Copyright of David Torrance ©

Unadorned facade Image: Lucas B. Salles

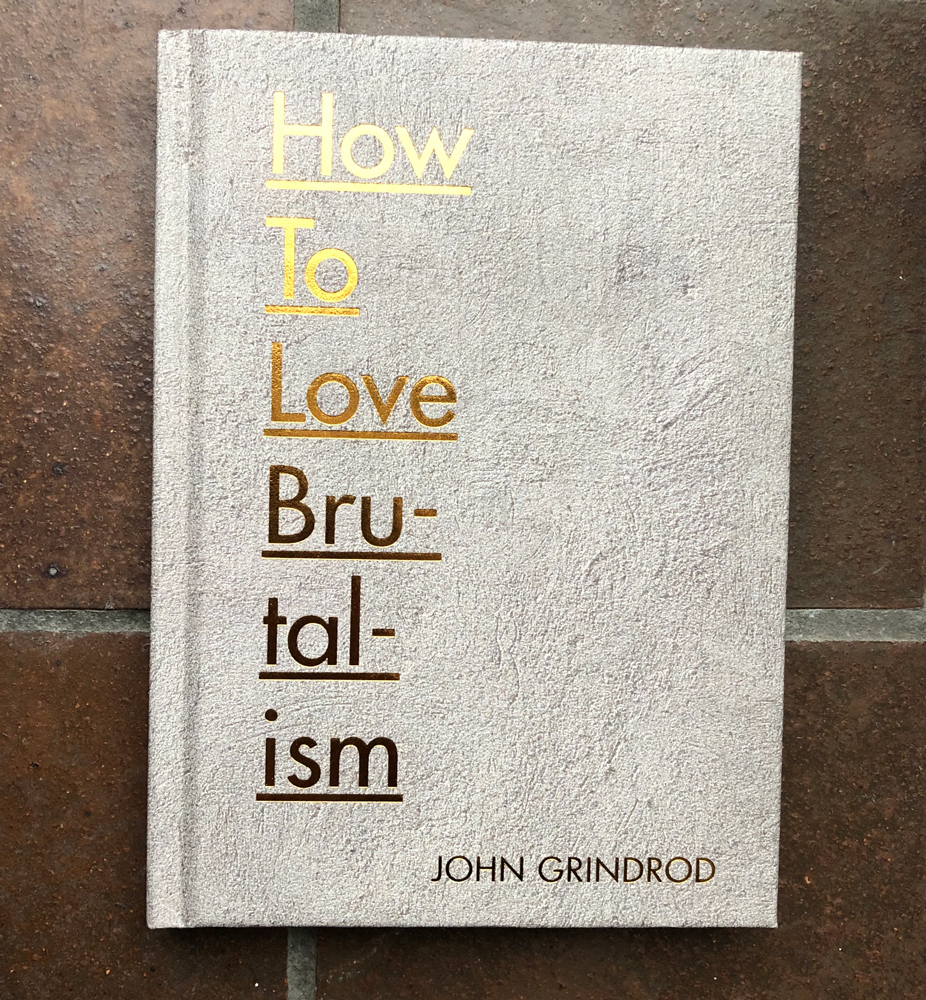

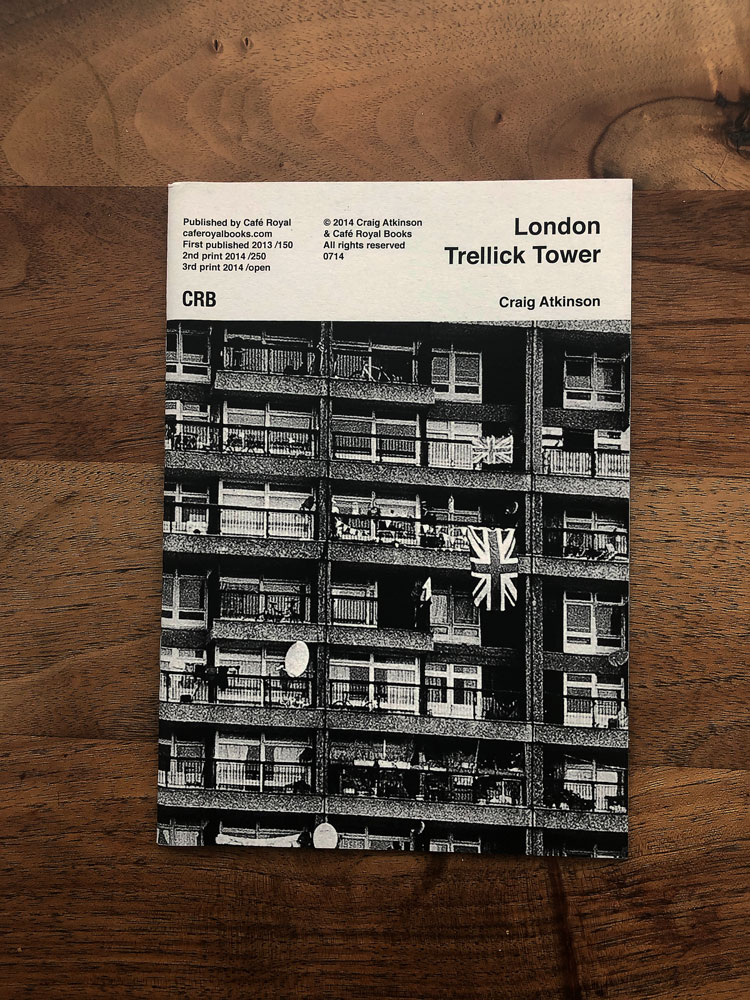

GREYSCAPE LOVES