Prague, Löbau and back again

Greyscape on the Road

Baba district, Prague

A moment of exquisite Modernist pleasure has to be an excellent reason for a road trip. Who could resist the opportunity to spend the night in a famed modernist family home, regardless that it is an awfully long way from all the usual German architecture hotspots? What a stay in Haus Schminke offers is the chance to road-test a perfectly designed historic house and the excuse to take a closer look at the former GDR. And so we planned to visit Löbau in Lower Saxony.

Flying in from London, we quickly discovered, was complicated. However, it turned out that Prague was the perfect starting point, allowing us to take in some of its unique Modernist and Brutalist buildings before we hit the road. It is also a reminder of just how close the German border is. We crossed the border to Löbau, then later back again to visit Mariánské Lázně one of three spa town jewels, to ‘take the waters’, enjoy a very non-Californian spa, marvel at the outstanding Brutalist Hotel Thermal, and consider the unusual Hotel Pupp, location for Daniel Craig’s 2006 Casino Royale.

Hotel Thermal Karlovy Vary

Driving in from Prague airport into the city we passed the elegant villas of Hanspaulka in Prague’s Dejvice quarter; tasteful, individual, each set in a large garden and home to ambassadors and the wealthy. Our destination was The Julius, Prague, an 1891 Neo-Renaissance building, modernised by Maximilian Spielman in the early 1920s. While The Julius Prague is focused on comfort and efficiency, which it and its charming staff team do extremely well, their building is actually a bit of a stand against Modernism.

The Julius, Prague

Modernism was the design vogue in 1920s and ‘30s Prague. Spielman, an Austrian architect, was an expert in “historicising styles”. He worked on the Villa Petschek designed by Otto Petschek, its owner. While ultra-modern in its comforts and fittings, the Villa is a Beaux Art building in a Neo-Baroque design. You may well have seen grainy black and white pictures of the building being visited by Hitler and it became the notorious HQ of the Gestapo during the occupation. The Petscheks, a Jewish family, fortunately, escaped the Nazis. The villa is now the residence of the US ambassador to the Czech Republic. Back to The Julius, Prague and Spielmann’s classical protest against Modernism. It was just right for our stay, very comfortable and relaxed, elegant and understated, a short stroll to the historic centre of Prague but sufficient distance away from the boisterous haunts of raucous Pilsner-fueled bachelor parties.

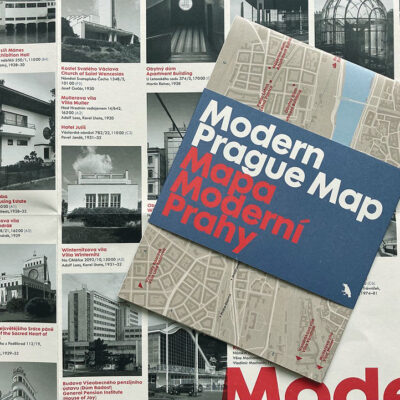

Prague’s history, its charming streets, excellent food and reasonable prices make it rightly a destination for many tourists. Arriving on a Friday afternoon, we headed the next morning to the Baba residential district on a hill above the city centre.

Baba District, Prague

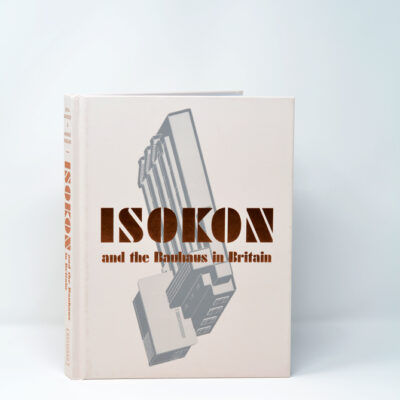

In 1928, a year after the Deutscher Wekbund opened the Weissenhof Estate of 33 Modernist buildings containing 60 residences above Stuttgart, the Czech Werkbund also decided on the construction of a housing estate. Successful architects, including Adolf Loos designed 33 Functionalist villas. Functionalism was enthusiastically received in Czechoslovakia, a new nation created in the aftermath of the Great War out of pieces of the beaten Austro-Hungarian Empire. Czechoslovakia pursued modernity, industrial excellence and the form and purpose of Functionalism, which adopted Le Corbusier’s vision of unadorned buildings designed to fulfil their purpose suited the prevailing vision. In Brno, Villa Tugendhat by Mies van der Rohe and Villa Müller in Prague by Adolf Loos in 1930 are exemplars of the Functionalist design philosophy. Much of the Bata Shoe Company’s development of Zlín is Functionalist, and Bata’s enlightened industrial enterprise led to its expansion, even to Tilbury in Essex.

The Wiessenhof project envisaged pre-fabricated materials being used to make affordable homes, but that really didn’t work out. Great designs, but expensive to build. Baba similarly aimed to provide economically priced homes for working people, but the plan for uniformity gave way to individually designed villas. Now the three parallel streets that compose the Baba houses are becoming more and more fashionable and middle-class.

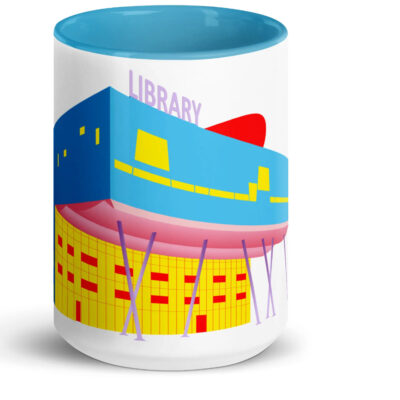

DBK Shopping Centre architects Vera Machoninova and Vladimir Machonin

Vera Machinova and her husband Vladimir Machonin are celebrated for their Brutalist architecture, and so we visited the DBK Shopping Centre in Prague. They also designed the famous Czech Embassy in Berlin and the monumental Hotel Thermal in Karlovy Vary (which we visited on our way back from Haus Schminke). Their working lives as architects were cut short in 1968 simply because they had the courage to show support for Czechoslovakia’s reformist leader Alexander Dubček’s whose “Prague Spring” was cut brutally short by the Red Army marching into the city, arresting the government and re-asserting the iron grip of Soviet communism.

The Sudetenland, named after the Sudeten Mountains but extending well beyond those mountains, was adjacent to the pre-1938 border with Germany. The several million ethnic Germans in its population gave a lot of vociferous support to the Nazis and it was Hitler’s belligerent threats that led to the Munich Agreement in 1938 when Great Britain and France, without involving the Czech government, bargained away the Sudetenland in return for Hitler’s lying promise that Germany had no more territorial demands in Europe. Without its defences at the border, Czechoslovakia was easy pickings for Nazi Germany. At the end of WWII, the Allies agreed that the Sudeten Germans could be deported, and in the months after the German surrender in 1945, that’s what happened.

With the communists taking power in Czechoslovakia, the border became harder, part of the fearful Iron Curtain across Europe. Driving past the fields and thickly forested hills of the region on our way to Lobau, we saw abandoned watch towers, pointless sentries on what used to be a guarded, dangerous frontier.

At a corner, in fact, a roundabout, where the Czech Republic, Poland and Germany meet, with not a guard post or border marked in modern, peaceful Europe, we turned towards the town of Lobau, arriving on Sunday afternoon – don’t think they get many tourists in Löbau.

Haus Schminke Winter Garden

The Haus Schminke is situated on a quiet street, its neighbours a few comfortable looking chalet style homes and to one side the Schminke factory, rather Willy Wonka-ish, brick built with a tall chimney but some Hans Scharoun Modernist additions. On the other side of the exquisitely landscaped gardens of the Haus Schminke is a settlement of datschen, somewhere between British allotment gardens and Russian dachas. Cultivated plots of vegetables and flowers, each with a small or not-so-small shed or rather grander cabin, divided from one another by immaculately tended hedges. Here is Haus Schminke and here we stayed the night and woke the next morning, feeling so much closer to the reality of living in a revolutionary home. The next morning we met with Julia Bojaryn from the Stiftung Haus Schminke, the foundation key to the preservation and restoration of Hans Scharoun’s Modernist treasure.

We’re going to write more about our stay in Haus Schminke but it is to be recommended and the stifling does welcome guests, please contact them here. But here’s a taster, as it were. The kitchen is one of few remaining “Frankfurt Kitchens” designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, ergonomic, hygienic, efficient and a delight to use because it really works. This is an experience you can’t get by simply visiting a house as was waking up in the morning in the guest room (we could have chosen any bedroom we liked but felt the guest room was most appropriate) and drinking coffee on the terrace.

Frankfurt Kitchen in Haus Schminke

We could explore the whole house, from its huge cellar for the storage of fresh produce (Charlotte Schminke believed in good, fresh vegetables), the sewing room, the dark room, all in the basement, to each bedroom. We saw how the Schminkes lived; they originally wanted separate bedrooms to have their own space but settled for being able to curtain their areas off from one another in the main bedroom.

The house works and in it, a family was raised. Its story, its strange story, a story deeply discomforting in parts, isn’t over and Haus Schminke will represent the good of Modernism.

We left Löbau and headed to nearby Görlitz, where the former department store, Kaufhaus, an Art Nouveau construction, was used as the location for the hotel lobby in Wes Anderson’s The Grand Hotel Budapest. Other spots all over the town are used as locations in the movie. We spent less time there than we did at another Art Nouveau building, the hauntingly beautiful and, now, restored synagogue. While the synagogue was spared from destruction on Kristallnacht, it fell into ruin because there were no Jews left in the town.

The Spa Colonnade Mariánské Lázně

Photo: Mr. Přerovský, archive of the Medical Spa Mariánské Lázně, a.s.

Leaving Görlitz, we drove on busy roads through the outskirts of Dresden, firebombed by the RAF in February 1945, back across the Czech border to Mariánské Lázně, along with Karlovy Vary and Františkovy Lázně being the most famous spa towns in Czechia. We stayed at the Hotel Nové Lázně, which, like most of the many hotels and buildings, is Neo-Clasical in style, grand and, rather empty. In the nineteenth century, the spa towns grew into large and fashionable retreats where the well-to-do and the not-so-well-off would flock to take the waters. For the British, there were spa towns, Bath, and Leamington Spa but in central and Eastern Europe, the spas and thermal springs developed into sophisticated resorts. Under the communists, the towns took to sending deserving workers to recover and revive in the spas from their Stakhanovite labours while, naturally, keeping the best for the party elite.

With the fall of communism, the spa towns enjoyed a renaissance attracting in ever larger numbers wealthy Russians for spa treatments and medical tourism. The spas are high-end but without the New Age relaxation and meditation music familiar in the US and Britain and not a crystal in sight. Massage is firm and be ready to stark naked, without little paper modesty pants.

Putin’s war on Ukraine has put a stop to Russian visitors and while there are people eager to enjoy the spas as well as Ukrainian refugees housed in some hotels, business is down. The Grand Hotel Pup in Karlovy Vary, the location for the poker game at the heart of Daniel Craig’s first outing as James Bond in Casino Royale, has a sense of waiting for the return of high-rollers with money to lavish – and right now, none of those folk are coming.

Moser Glass Factory, Karlovy Vary

For us there were two especial highlights; a visit to the Moser glass factory and the Hotel Thermal. Moser. still makes its glass objects as it always has, by hand by craftspeople with the most delicate touch and the physical toughness to work in high temperatures while handling incredibly hot and heavy glass. Moser’s breakthrough was to develop a lead-free luxury crystal glass. The Moser factory is still in Karlovy Vary. It survived and even managed to thrive to an extend under communism and now continues to be the best of the Czech glass, making it probably the best in the world.

And then, we found the Hotel Thermal, designed as mentioned earlier by Vera Machinova and Vladimir Machonin. Not so long ago the hotel was under threat of demolition, so much so a campaign to save it was mounted, see here. Fortunately, the hotel has been saved. it plays a key part in the annual Karlovy Vary Film Festival and its renovation is restoring that wonderful 1970s vibe.

Modernist architecture was a departure, it had goals, a purpose, an aim to improve the lives of the inhabitants but all these wonderful buildings are in and not outside of history. A sense of that history is key to understanding the buildings.

Hotel Thermal facade and cinema, Karlovy Vary

Where we stayed

Reitenbergerova 53, 353 01 Mariánské Lázně, Czech Republic

Senovazne namesti 939/3, 110 00 Prague 1, Czech Republic

Kirschallee 1b, 02708 Löbau

All images Howard Morris © unless otherwise stated