Post-Socialist Realism – Contemporary Soviet Collages

Tamara Stoffers is a Dutch artist creating photomontages using original Soviet-era images. We love her work. Tamara’s gesamtkunstwerk, a place that doubles as both a creative and living space is in Deventer in the Netherlands. It isn’t simply a backdrop for her art, it is a place where visitors can step back in time and experience her vision of a 1960s Soviet communal apartment.

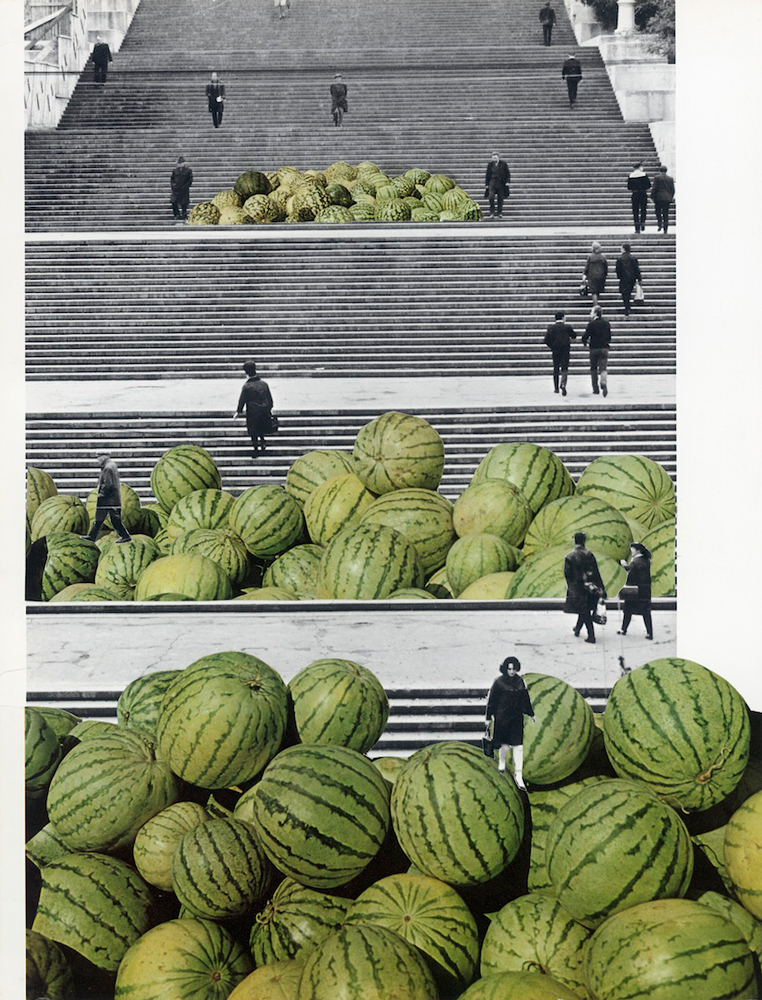

Tashkent 1971

Greyscape spoke to Tamara about her home, her motivation, exhibitions, her fascination for the subject matter.

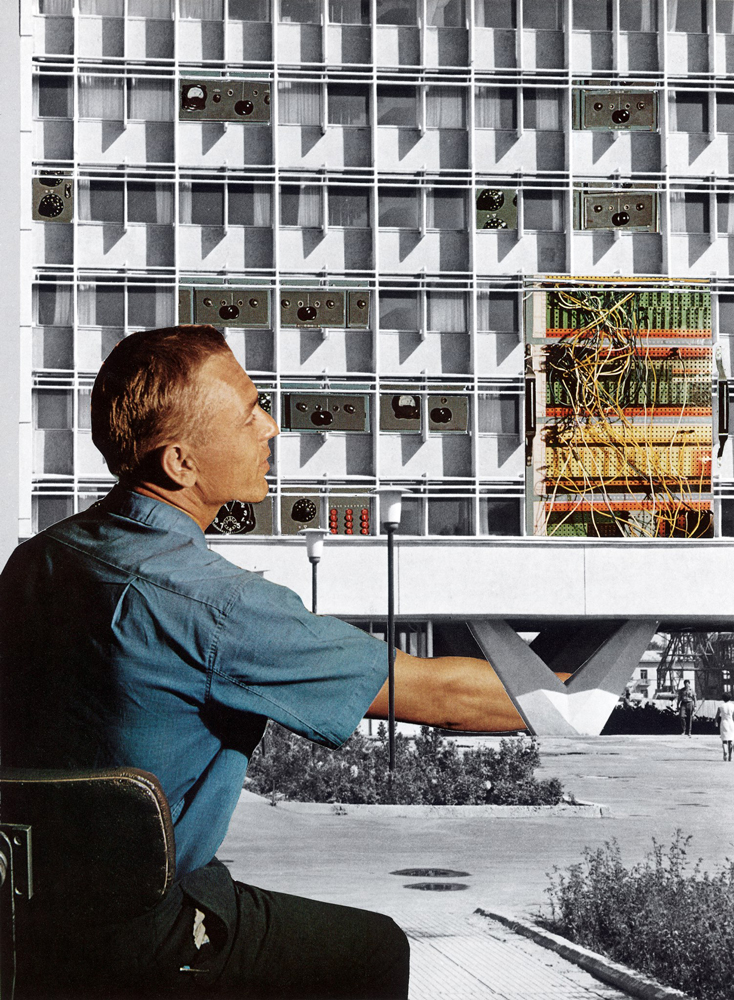

‘The USSR has been my focus for the last six years. It has presented itself in every way imaginable as the polar opposite of my familiar Dutch environment. I’m especially fascinated by functionalist architecture and the way Soviet ideology influenced fine and applied arts. It is hard to grasp the degree to which politics became intertwined with every part of daily life, from the centrally set price of your teacup to the provided forms of entertainment during leisure time.

Especially interesting is the way national achievements influenced design, the ‘space-age’ brought Saturn and rocket-shaped vacuum cleaners and futuristic shaped clocks and lamps into family homes.

Potemkin Stairs 1971

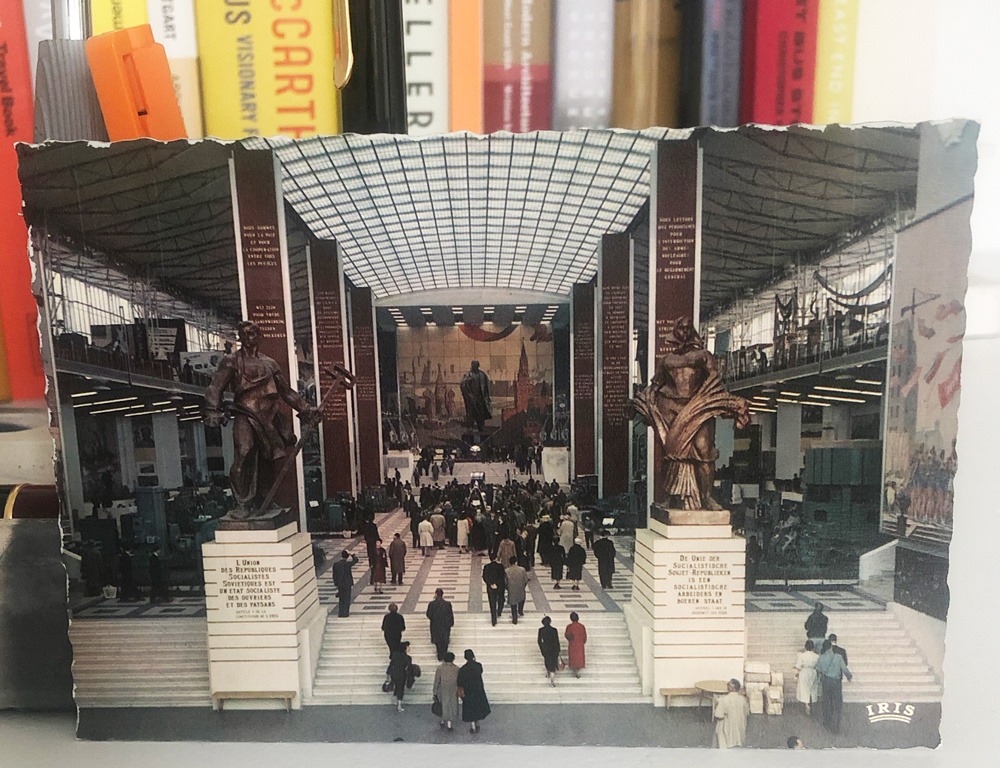

My fascination started when I was an art student in Groningen rummaging through second-hand shops. My attention was caught by a chance finding of a book from the early ’60s about Moscow. It featured the first wave of five-storey flats, which were later referred to as Khrushchevki. Photos captured streets decorated with rousing red banners praising social development, optimistic youths in Young Pioneer outfits and female chemists collectively smiling at the camera. Ordinary relatable people were presented as heroes.

Previously painting had been my main focus as a medium to express myself, but I was always experimenting with using different materials simultaneously. The technique of collage is especially interesting and challenging, I’m restricted by the available materials, working within certain limitations based on the original printed images. It is not a blank canvas with infinite possibilities. Over time my medium of choice shifted and organically, subjects that grabbed my attention became more and more visible in my work.

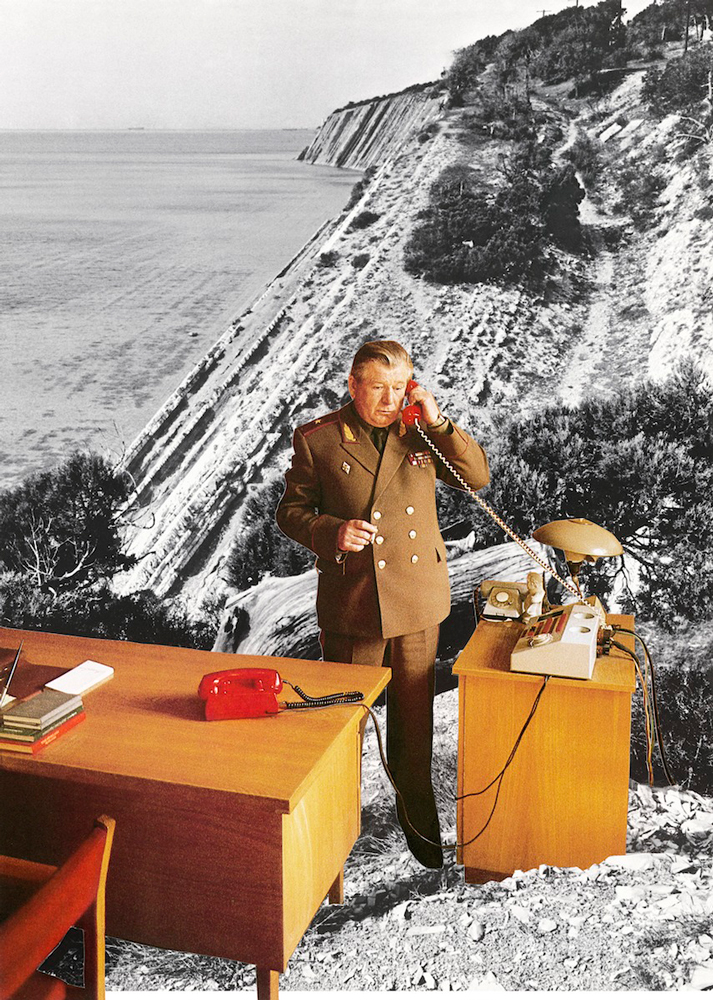

Novorossiysk

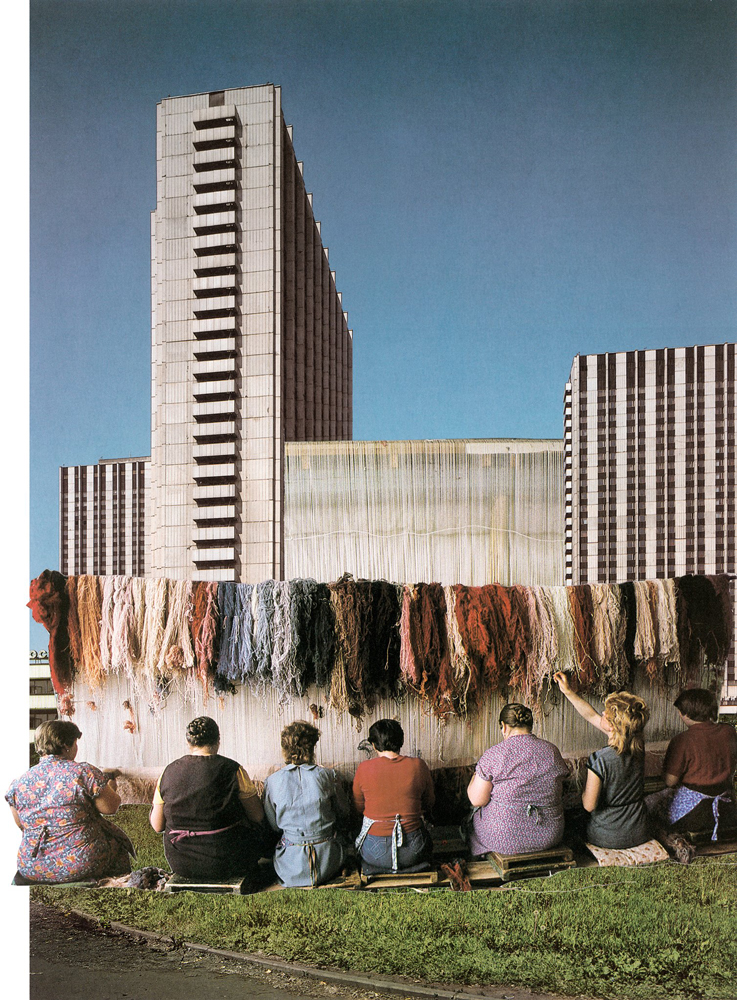

Naberezhnye Chelny 1980

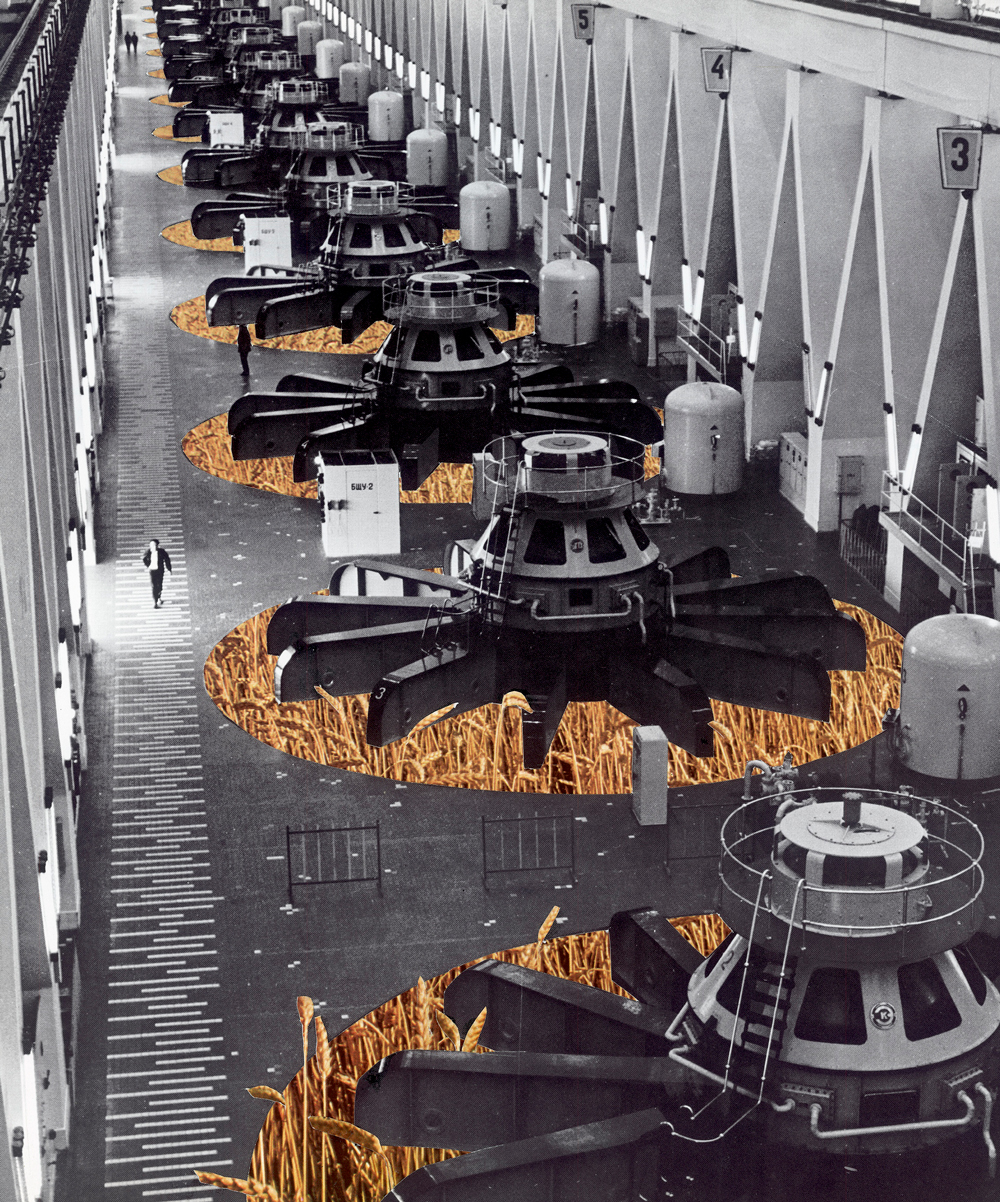

I chose collage as the creative process to interpret those images. It is also my way of researching, deepening my knowledge and gaining a more profound understanding of my subject. I used to and continue to use visual associations, manually composing images from my, by now, large archive which covers from the ‘60s up until Glasnost in 1986. It is important to me while making collages to retain the atmosphere captured in the original photographs. There is room for imperfection, the manual cuts and printing grids within the collages remain visible. While merging images I intuitively look for photographs taken from a similar perspective. It creates a logic within the final results that makes the collage look organic.’

Tell us about your studio, your home, which is itself a work of art.

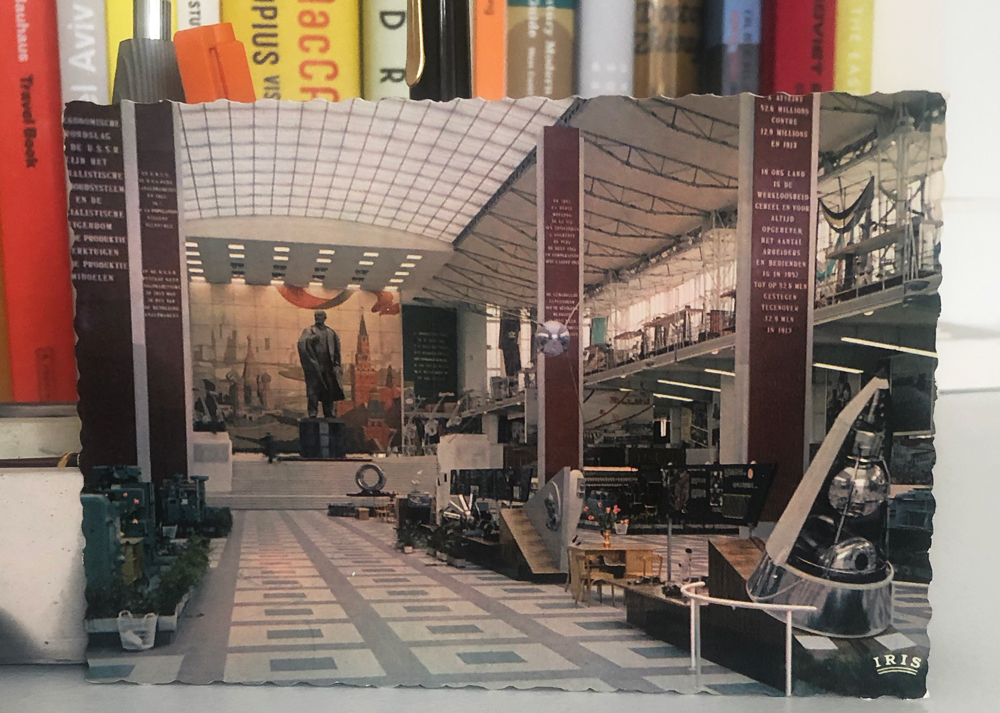

‘It’s a place that gives context to the collages and a way of life. The atmosphere of my room and the collages are the same, my creations feed upon this environment.

I approach it as a functional piece of art, composed with great attention to detail and mindful of the atmosphere. A means to take me and my visitors back together. From my radio floats the voice of Edita Pieha singing about noisy neighbours and trolleybuses. There’s a carpet on my wall, banners with badges. The furniture is made of dark brown, it’s home to desk-sized busts of Lenin and there are lots of books from and about the era.

Tamara Stoffers’ gesamtkunstwerk

It gives me joy to immerse myself in the subject and create an environment in which it is present and remains relevant. It creates an escape from our reality where the future seems inherently threatening and points us back towards a time where the future was presented as something filled with possibilities.’

And has learning Russian been an important part of developing these works?

‘Learning Russian has been like a key unlocking a door with access to specific regional words and expressions, enabling me to decipher the slogans on banners and understand the mentality and culture. I’m rather obsessed with this. The heavy use of abbreviations during the Soviet era reminds me of Orwell’s 1984. The messages from banner, to the media, to the factory floor carried a lot of ideological meaning and their initial message felt meaningless in no small part due to their endless repetition. There is an interesting tension. People began to not notice them any more they became almost too familiar.

Of course, one is always mindful that the picture books I use were purposefully created as a propaganda tool to support the goals of the regime. Their content had to be approved by a Ministry before publication. This nods to the important role attributed to art as a core element of education and inspiration for the Soviet worker throughout the history of the USSR.’

Bratsk 1971

Kalinin Prospekt 1971

Art as a tool in Soviet Society

‘Shortly after the revolution, Lenin dictated the direction art should take. He said

‘Art belongs to the people. It must leave its deepest roots in the very thick of the working masses. It should be understood for the masses and loved by them. It must unite the feelings, thoughts and the will of the masses and raise them. It should awaken artists in them and develop them’.

‘It demands of the artist the truthful, historically concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development. Moreover, the truthfulness and historical concreteness of the artistic representation of reality must be linked with the task of ideological transformation and education of workers in the spirit of socialism.’

This led to art becoming a mouthpiece for state propaganda and narrowed down the subjects portrayed to those depicting daily life of idealized ordinary people following the aims of the socialist party.

Dobroe 1980

There was very little freedom of expression. Because art was mostly financed by the government, rarely by an individual, artists who didn’t follow their ideals were quickly forced to either adjust or leave the profession. Even Malevich went back from Suprematism to figuration after being deemed ‘decadent’.

Putting aside the restrictions there were some interesting aspects. Since art had this distinct function of being made for the people, it was also made visible by displaying it in public places. There were decorative paintings and mosaics in indoor markets, mosaics in the bus stop and ceramic arrangements on the side of houses. There was no intellectualism surrounding art, it was accessible to everyone. However, the majority of people didn’t feel it spoke to them.

Akademgorodok 1971

Kursk 1980

People have an idea of the lack of freedom in the Stalinist USSR, did things change with Krushchev’s thaw ‘ottepel’?

More freedom was allowed under Khrushchev. He stated in 1957

‘If you try to control your artists too tightly, there will be no clashing of opinions, consequently no criticism, and consequently no truth. There will be just a gloomy stereotype, boring and useless.’

After this came a period known as the ‘thaw’ which theoretically opened up many possibilities for artists and writers. Even Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago was published. Practically, however, art still served the ideals of the state and would continue to do so until Perestroika. This can be clearly seen in the books dedicated to depicting in a positive light the lives of people spread across the USSR’s vast republics.

Were the photographs truthful?

‘Some photos were staged and the photographers were selective. It’s clear to us today that the images likely didn’t correspond for everyone with the reality on the ground. Yet the books do have a certain quality that simple fairytale books don’t have. I don’t think people looking at that time believed it was showing a present reality, but they convinced themselves that it would have been possible to build up a well-functioning communist society within their lifetime.

That isn’t downplaying the problems of inequality. The Soviet elite had some clear advantages, being able to cut the line, receiving consumer goods such as television sets and fridges, as well as ‘deficit’ foods, (a keyword from the era, ‘deficit’ was often used in Russia to describe a product which was ‘rare’ or not easy to obtain). It was not possible to hide these privileges from ordinary people. And whilst clearly people could see what was happening, I do think that from the early ‘60s until the middle ‘70s people were genuinely optimistic about their prospects. Khrushchev predicted in 1961 that within 20 years everyone would live in a developed communist society and it seems as if many people believed this could be achieved if they would collectively work towards it.

Voronezh 1971

Rusanovka 1980

Party officials made efforts to convince workers that the problem of shortages was being addressed. In the foreseeable future (with an unspecified date) everyone would be able to get their hands on shoes that would fit, that having a car would be an attainable dream and that in the evening they could watch television in their own compact convenient apartment.’

You’ve exhibited in Moscow as well as widely in Western Europe, what were the different reactions?

‘I showed my collages first in Rotterdam, Brussels and Stockholm before showing them in Moscow. It’s always fascinating to listen to as well as see people’s reactions.

Shortly after my interest was sparked I started learning Russian, it has taken me five years of solitary learning to achieve level B2. It has been invaluable in understanding the culture and history because it has enabled me to access many sources and to be able to communicate directly with people from Russia and the Ukraine. The Moscow showing of my work being a perfect case in point.

Bessarabska 1975

Izmailovo 1981

Western European visitors discussed the aesthetics of the collages, Russians talked about the content. Being surrounded by people who closely experienced the reality of life in the USSR made the conversation interesting and personal. Some were nostalgic, some condemning, but always emotional about their past. The images seemed to trigger their own memories, especially from their childhood. They talked about being in the Youth Pioneer organisation and attending summer camps, how they still vividly remember taking the oath they had to pronounce during their initiation.

Some reminisced about the huge lines to buy basics such as bread or sausage. Some hinted at a family member being repressed during the regime of Stalin. Everyone above the age of forty was eager to share something.

I think especially my young generation tends to forget that the USSR is not something from a very distant past, it is very much in people’s living memory. There are still generations in Russia living amongst us who grew up during that era and were educated accordingly and similarly in the West with clear memories of the Cold War. The subject still triggers deep emotion. The power of photography to initiate reflection and give room for a depoliticized vulnerable conversation has become something I have wanted to explore more deeply ever since.

Food deficit

In one exchange an older woman was talking about the importance of the dacha she was assigned during times of food ‘deficit’. She worked as a teacher in the city. At the weekend she headed to her dacha to maintain her vegetable garden. The fruits and vegetables would be preserved in jars ready for the long winter. The lack of choice in fresh fruits and vegetables in the stores gave her a feeling of urgency. She needed to dedicate time and effort into learning how to do gardening. Remembered, was the cult around it, how gardening was promoted in ‘Houses of Culture’ and through lectures and competitions. She would exchange seeds for flowers with neighbours and family members as they were hard to acquire. At the end of summer, her children would help her harvest. They would be rewarded with fresh berry lemonade.

It was labour-intensive, but she remembered it as something positive. According to her, people were grateful for what they had. They know how long it took for something to grow and how much energy and dedication was needed to get a good harvest. It bore no comparison to the dull produce that could be purchased from a store. She said that the experience of living in the USSR had left a deep sense that it is a sin to throw away food or leftovers.’

Art in Everyday Life – dressing for change

‘I’m very fond of the constructivist movement. Especially interesting is the publication ‘Art in everyday life’ published in 1925. It features clothing designs by Nadzadha Lamanova together with Vera Mukhina, known as the sculptor of ‘Worker and Kolkhoz woman’, which were easy to make at home. Amongst the designs was a dress made out of square peasants scarves. It also features various ornaments and designs for public space with clear Soviet symbols such as the hammer and sickle, as well as grain and books. All the illustrations are executed in a bold limited colour scheme of red, black and a little green. There is a design for a movable theatre, public newspaper display stands, the first examples of Pioneer costumes, practical clothing as well as theatrical costumes.

Kostroma 1971

It was published just a few years after the ‘Prozodezhda’ movement, through which a small group of artists tried to design a fully new type of timeless clothing adjusted to the needs and idea of ‘a new society’. They were also rather simple in construction and featured striking geometric ornaments and bold lines. Both the designs from the Prozodezhda movement and ‘Art in everyday life’ never gained the widespread popularity the artists were hoping for. However, the illustrations remain and they are a gem to look at.’

Are the messages of the original photographs you have used re-purposed or is some of their story still relevant?

‘Through my process of cutting and pasting, the images of the USSR are distorted into surreal dreamlike situations and environments. Their origin remains visible, but they get a new life deprived of their original context. Through my collages, my aim is not to dishonour the artistic intentions of the photographers. By using the topics of glorified labour and progress, which were very strongly represented in the original books, I feel rather affiliated with the movement of Socialist Realism.

At home with Tamara in her gesamtkunstwerk

It has become clear that the artistic relics of the Soviet era are in many countries with a recent historic connection to the Soviet Union are deemed irrelevant and condemned. My hope is that approaching history through the medium of collage will grant viewers affected by the topic enough distance to verbally express their thoughts, memories and associations in a depoliticized manner. But more importantly, it might encourage them to reflect and see the past as something that should be neither be rejected or worshipped. Instead, it should be a reference point to draw lessons from.’

Do you have any plans for 2020?

I am fully dedicated to my five-year plan and have plenty of ideas to bring it to reality!

All images unless otherwise noted are the Copyright of Tamara Stoffers

Do go and see Tamara’s portfolio on her website (her collages are for sale); www.tamarastoffers.com and follow her Instagram at @tamarastoffers .

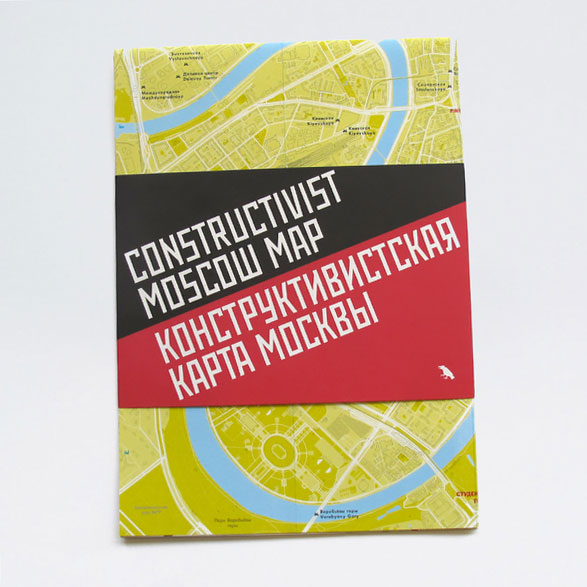

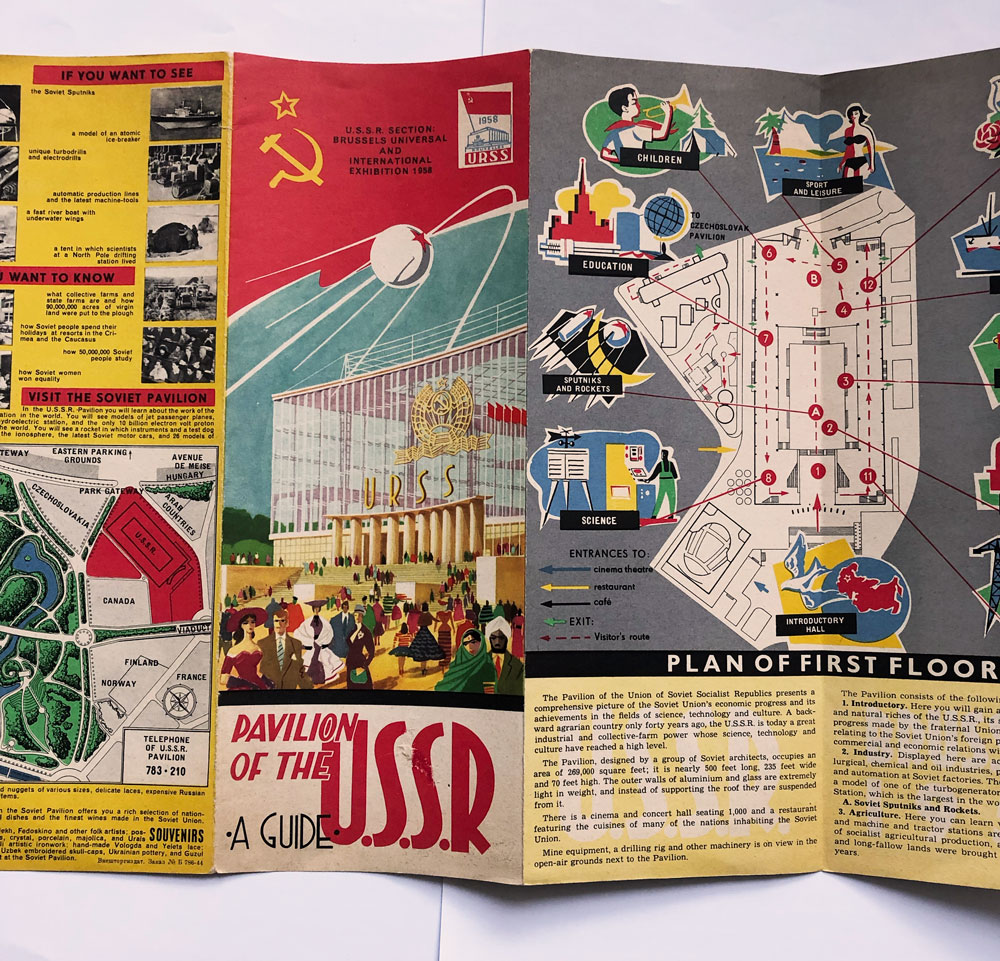

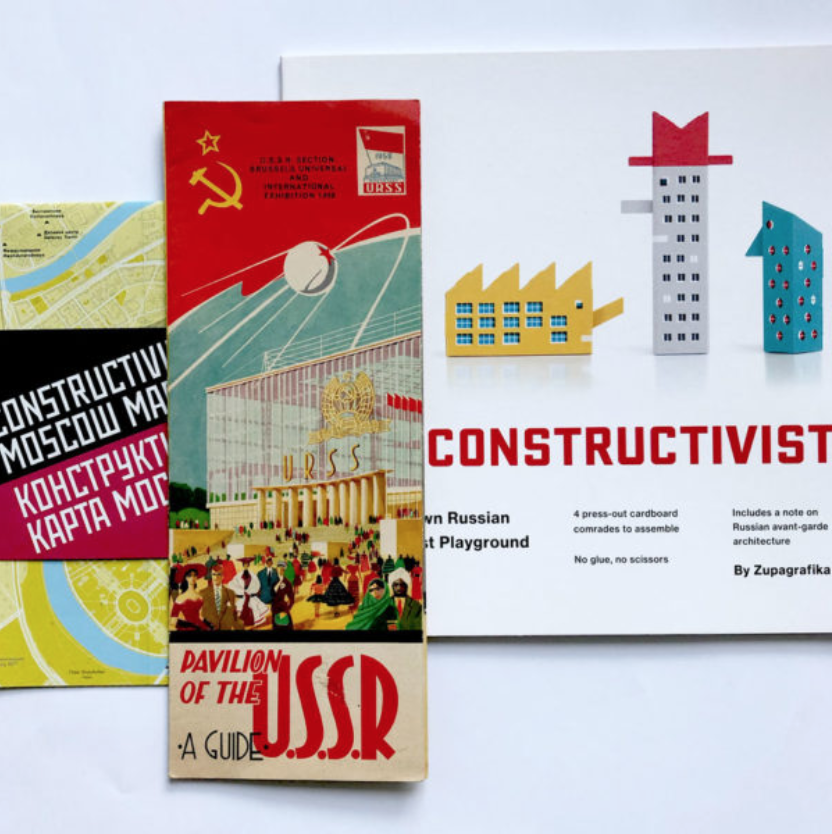

Greyscape Loves

Vintage Expo 58 Soviet Pavilion Brochure, The Constructivist: Build Your Own Russian Constructivist Playground, Constructivist Moscow Map