Modernism Was Framed: The Truth About Pruitt-Igoe

Why ‘July 15, 1972, at 3:32 pm (or thereabouts)’ wasn’t the day modernist architecture died

“The Pruitt-Igoe Myth”

One of the vaunting ambitions of modernist architecture, indeed a central tenet of its philosophy was to meet the pressing need for public housing. From the hundreds of manifestos and declarations published by its advocates between the end of the Great War and 1932, Professor Paul Greenhalgh, Director, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Professor of Art History, extracts 12 defining characteristics of modernism, one being “social morality”. Population growth, emigration from the country to cities to labour in the continuing industrialisation, led to vast numbers of people by the early twentieth century reduced to living in wretched, squalid urban slums. St Louis, Missouri, like so many other cities, was faced with the need for affordable housing for the population the city had attracted.

Film-maker Chad Freidrichs’ documentary movie“The Pruitt-Igoe Myth” nails the persistent fallacy that the demolition of the massive Pruitt-Igoe public housing project in St Louis was just that.

Watch the 2-minute free trailer + link here to the full documentary

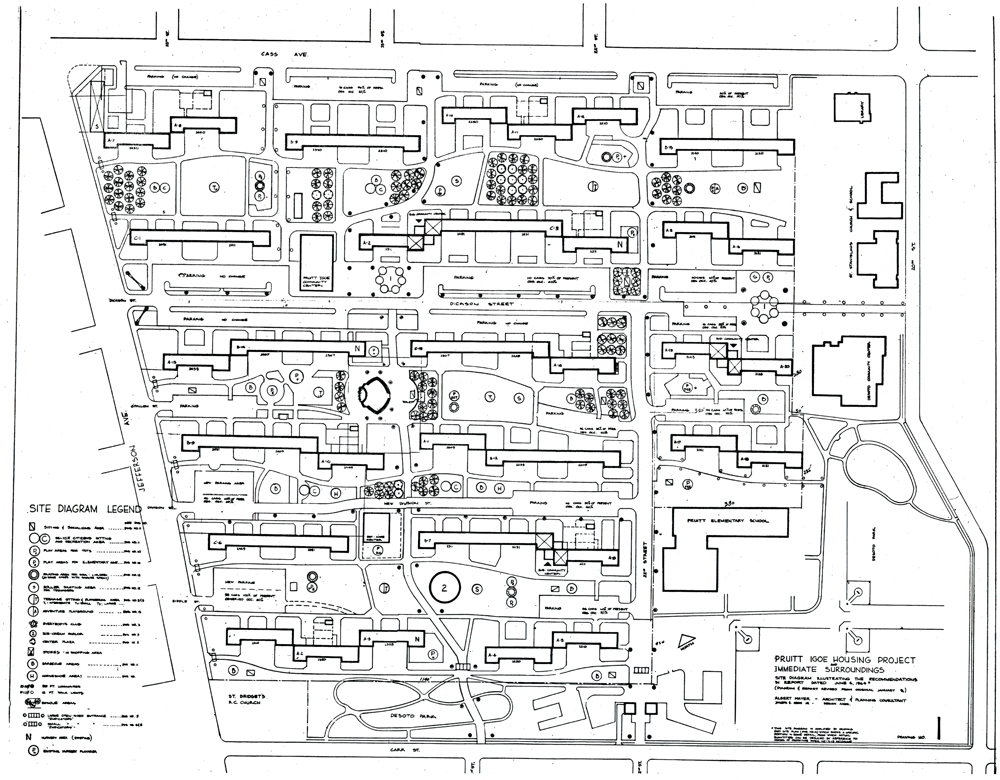

After a number of false dawns, in 1950, Minoru Yamasaki of Leinweber, Yamasaki & Hellmuth began the work of designing what became the Pruitt-Igoe development of 33, 11-storey blocks containing 2,870 apartments over a 57-acre site. Yamasaki applied the design precepts of Le Corbusier. Government funding was available and the city acquired the massive site using its powers to compulsorily acquire lots where necessary. There were great ambitions.

The residents had communal spaces, attention was paid to the outdoor areas, laundry rooms, skip-stop lifts, broad corridors, all intended to create community. The first residents moved in during 1954. But a number of key design elements had been nixed as too expensive. Originally the project was to be racially segregated but by the time of completion the Jim Crow laws allowing this had been made unlawful by the US Supreme Court. The project lasted 18 years.

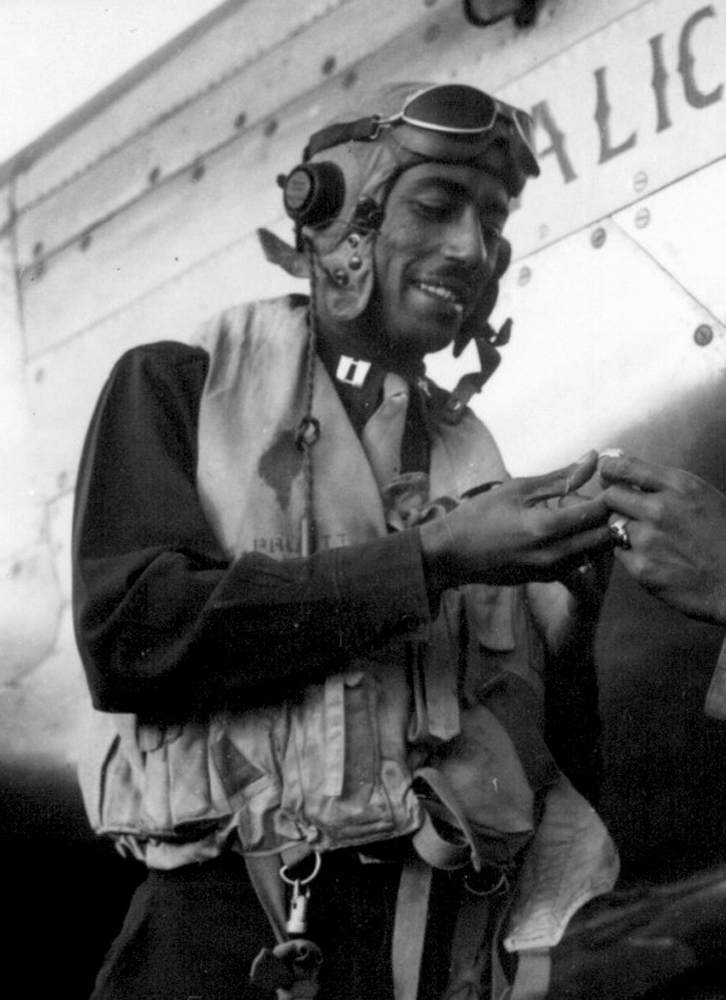

Wendell O Pruitt, Tuskagee Airman

Too soon the blocks began a slide into decay. Tenants couldn’t afford the rents and the authorities were unable or unwilling to maintain and repair. This is a story familiar in many places. Now, all that remains is a massive, almost abandoned site reoccupied by grass and trees, grainy photographs and the memories of those who wanted and struggled to keep a home.

On March 16, 1972, the first Pruitt-Igoe block was dynamited, the last demolished in 1973. By then the project was depopulated, decayed, unfit for habitation, infested with rodents and pests and crime.

It was Charles Jencks, cultural and architectural historian and post-modernist who famously declared in his 1977 book, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, the demolition on July 15 1972, as the death of modern architecture. And that pronouncement stuck. Modernist architecture was blamed for the failure of the project. Jencks’ opinion played into the biases of many opponents of the public housing project. Ignoring the economic reasons for failure, the constraints on cost, the flaws in the construction, the unaffordable maintenance and repair bills, the Jencks’ analysis became the received wisdom. And for many who considered Pruitt-Igoe had too strong an odour of socialism and disliked the whole idea of public-housing together with a deep and embedded racism, made it all too easy and expedient to blame the large number of Black American residents.

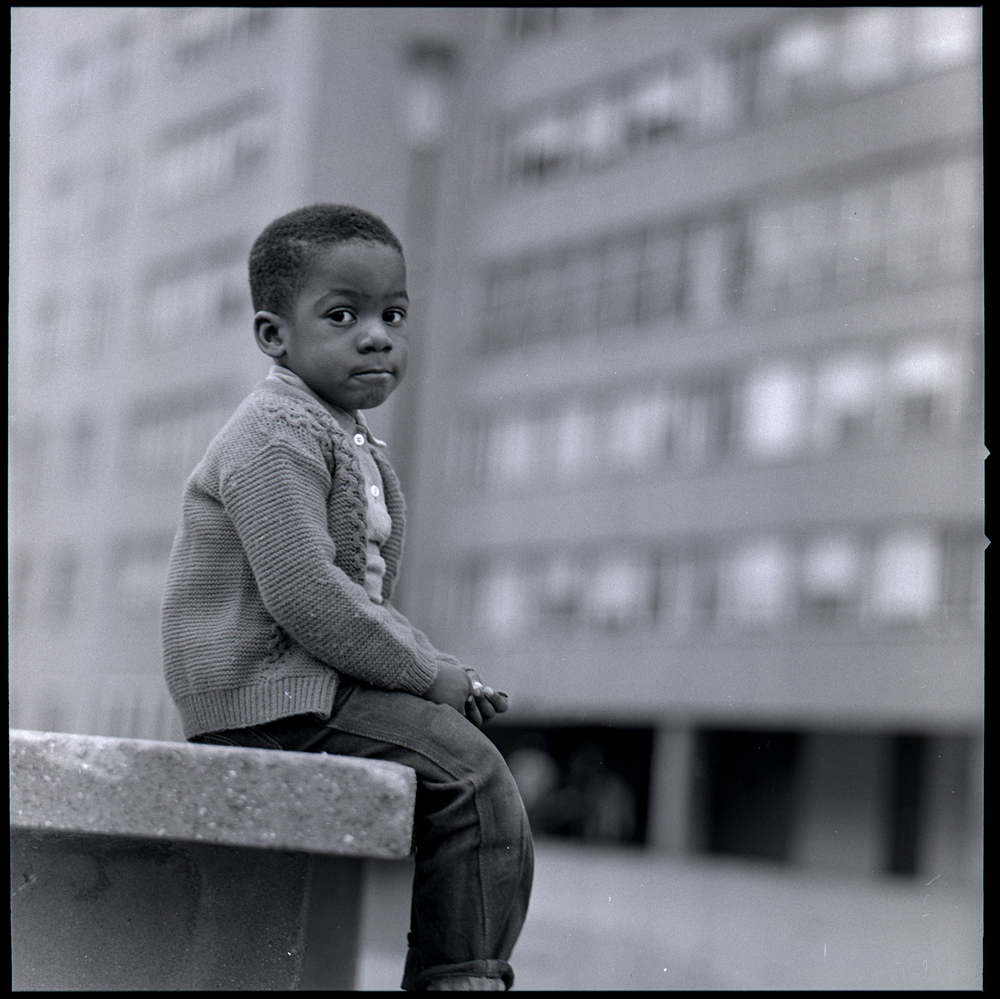

Home for thousands, Pruitt-Igoe

It was nearly 20 years before a reassessment of Pruitt-Igoe methodically dismembered the Jencks’ conclusion. The truth emerged in a paper by Katharine Grace Bristol of the University of California at Berkeley.

“This paper is an effort to debunk the myths associated with the demolition of the Pruitt-lgoe public housing project. In the seventeen years since its demise, this project has become a widely recognized symbol of architectural failure. Anyone remotely familiar with the recent history of American architecture knows to associate Pruitt-lgoe with the failure of High Modernism, and with the inadequacy of efforts to provide liveable environments for the poor. It is this association of the project’s demolition with the failure of modern architecture that constitutes the core of the Pruitt-lgoe myth. In place of the myth, this paper offers a brief history of Pruitt-lgoe that demonstrates how its construction and management were shaped by profoundly embedded economic and political conditions in post-war St. Louis. It then outlines show each successive retelling of the Pruitt-lgoe story in both the national and architectural press has added new distortions and misinterpretations of the original events. The paper concludes by offering an interpretation of the Pruitt-lgoe myth as mystification. By placing the responsibility for the failure of public housing on designers, the myth shifts attention from the institutional or structural sources of public housing problems.”

It wasn’t modernism that led to the decay of the Pruitt-Igoe project

But there isn’t a single Pruitt-Igoe myth.

Removing the layers of distortion needed Chad Freidrichs. He is an independent filmmaker, a description that barely does his invention and creativity justice. Aside from a technical competence in every area of movie-making from cinematography to editing, he produces, write and directs. But it was teaching at Stevens College in 2008 that led to his feature-length documentary,“The Pruitt-Igoe Myth”. Teaching was an epiphany for Chad. It enabled him to look at his work and art and develop insights as he taught film making. Pruitt-Igoe was discussed at the college and that was the start of Chad’s project.

The vision of Pruitt-Igoe, children visiting the library

Chad’s The Pruitt-Igoe Myth features a series of interviews with former Pruitt-Igoe residents. It is the witnesses who unfold the reality of what happened and what went wrong. These accounts credibly explode any idea that the residents of Pruitt-Igoe were feckless indigents, that they didn’t strive and fight to make the project a success that they or the design were to blame for the failure of the project. Or, worse, because of their colour they were incapable of respecting and caring for a decent home.

Pruitt-Igoe sought to apply Le Corbusier’s principles

Observing, exploring and recording is what Chad does. This isn’t polemic. It is an evidence-based investigation and its narrative carries the viewer along. The film lays to rest not just a single myth but three: first, what Chad calls the “local level myth” that the failure of Pruitt-Igoe was because it housed poor Black Americans. Then there is the “architectural myth”, originating from Charles Jencks’ critique. Thirdly, at the broadest level, is an anti-welfare critique of public housing, the myth that public housing is innately socialist and therefore, wrong.

Pruitt-Igoe was the hope of and for, many

One of Chad’s interviewees is Sylvester Brown Jr who lived in Pruitt-Igoe between 1964 and 1968. At first, the modernity of the family’s apartment, the space for each child to have her or his own bed, the appliances and conveniences were a revelation. But the problems were inescapable. Sylvester’s father, because he was able-bodied, couldn’t live in public subsidised housing and so when he spent the night with his family, had to do so secretly. The great wave of immigration to the city had in fact gone into reverse and the white working-class population were moving out as St Louis’ industries crumbled and to get away from the poor Black American population leaving the South and looking for a better life. The rents were unaffordable and there wasn’t the public money available.

As an adult, Sylvester became a columnist for the St Louis Post-Despatch and has written and spoken much about Pruitt-Igoe, about the good memories and the violence and decay as families lost a battle to make a home, a battle that was unwinnable.

Pruitt-Igoe collapse U.S. Image: Department of Housing and Urban Development (Second demolition)

The Pruitt-Igoe Myth is available on Vimeo. It is just one of Chad’s movies, which include The Experimental City an account of how, in the 1960s, a scientist and a team of experts, set out to develop a domed metropolis that would eradicate the waste of urban living. But locals and environmentalists rose up in protest, doubtful of the project’s utopian promise.

Nature has reclaimed the abandoned Pruitt-Igoe site

And what of the architect? Yamasaki’s misfortune wasn’t over. He regretted getting involved in the project. That wasn’t the end of Yamasaki’s association with destruction; it was he who designed the World Trade Towers in New York, destroyed in the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Projects like Pruitt-Igoe are a thing of the past and it’s suggested that only a third of project residents get an apartment in the developments built in their place.

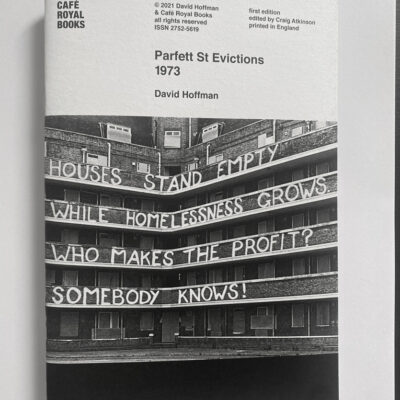

It would be fatuous to argue that the design played no role in the problems of Pruitt-Igoe, the alienation of residents, the challenge to build a cohesive community. After it all, it wasn’t the only well-intentioned social housing project that fell very much short of its ambitions, for example, Robin Hood Gardens in London. But it isn’t proof that modernist design is fatally flawed in meeting that central ambition of social morality.

Watch the full documentary: Link

Images 1 & 2: Pruitt-Igoe Image U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research Creative Commons