THE ASTONISHING MELNIKOV HOUSE

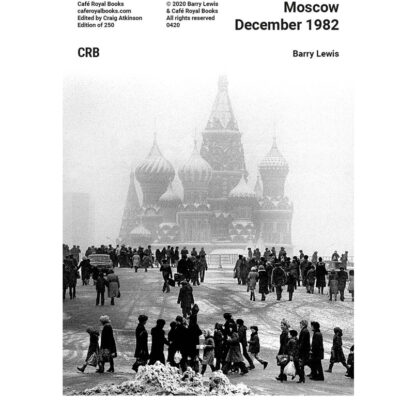

It’s a honeycomb, a fortress, a marvel of engineering, a house of invention and innovation, a family home for a prominent man and yet everyone slept in a single bedroom. The Melnikov House is an architectural gem in Moscow’s fashionable Arbat district.

This article was written before February 2022 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Greyscape stands with Ukraine.

Russian architect and artist Konstantin Melnikov was at the forefront of the Avant-Garde movement, respected and, for a time, untouchable. Whilst in the early 1920s it was hard to get planning permission for a private residence and then even harder to get suitable building materials in Moscow, he remained undeterred, adapting his design to the materials he could access.

His home and studio (1927-29) was built over three floors is composed of two intersecting cylindrical towers that were intrinsic to his advanced heating system. The top floor, flooded with light, is an architectural studio. This modern palace is a grand, glorious bold expression of Melnikov’s vision and a far cry from the bitter poverty into which he was born.

Growing up, he lived in a single room with his siblings and parents. The story goes that a local milkmaid noticed Konstantin’s talent for drawing and introduced him to one of her customers, a wealthy engineer who, in turn, educated Konstantin. At the age of 12 Melnikov had only been to school for two years, but by the time he was 20 (in 1910) he was a trained architect and artist.

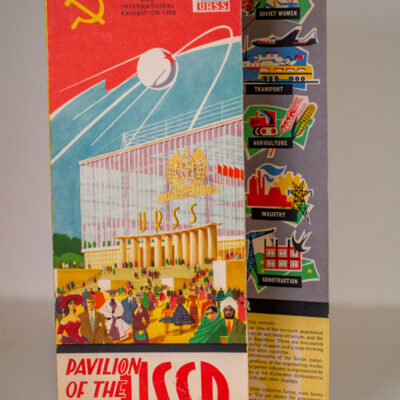

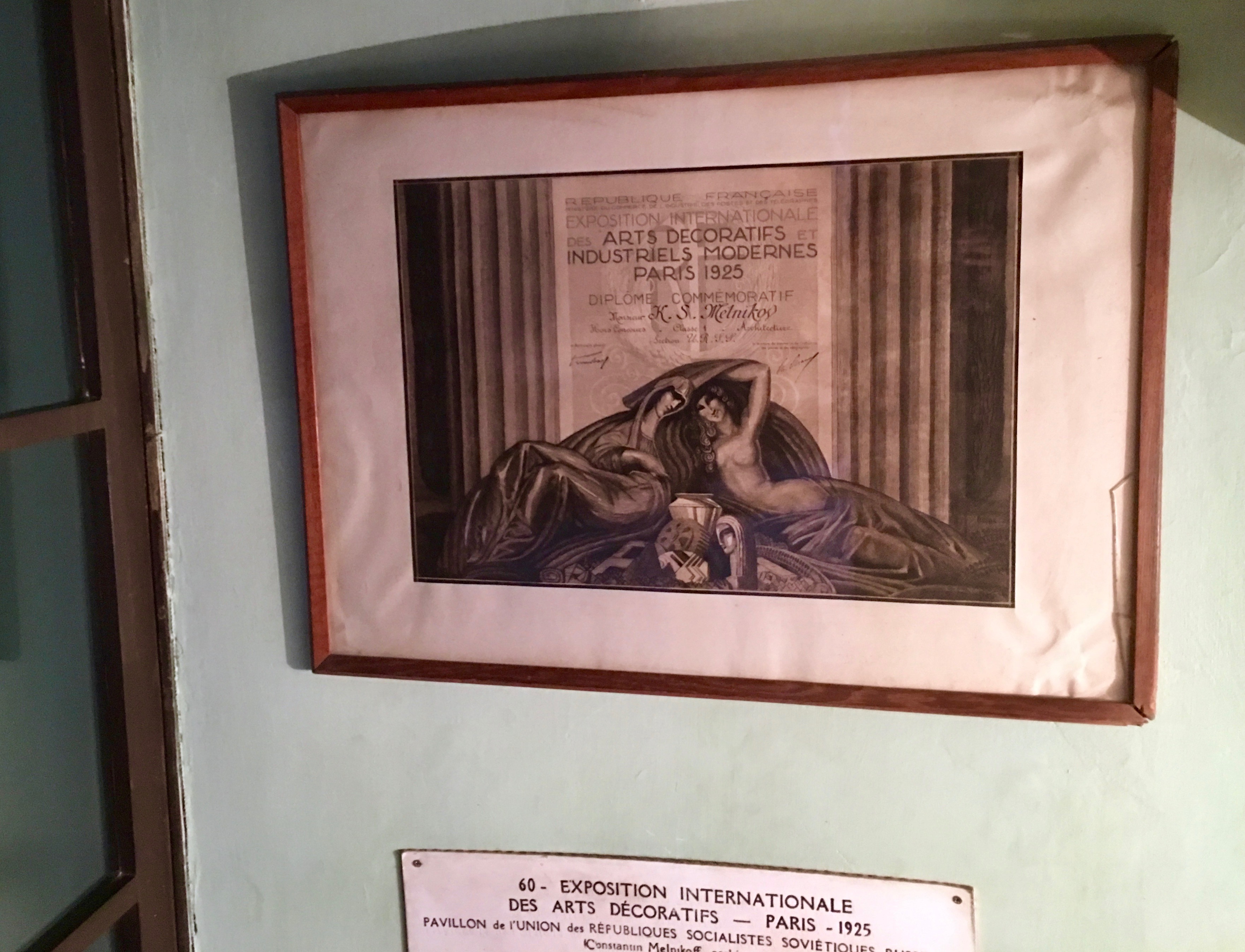

It’s so hard to know while living through it, but for Melnikov it was 1923 in which his career, life and ambitions fell into place, not least because it marked the beginning of a decade in which he was revered locally and abroad. As a well-known figure in Moscow, he was commissioned to design the Soviet Pavilion at the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratif et Industriels Modernes and it was here that he was brought him into contact with international designers.

Back home he was translating political thinking into bricks, cement and mortar. He was working on more than 20 buildings, included a Workers Club, the Bakhmetevsky Bus Garage and even an innovative car park design.

His most productive period in the public sphere coincided with the growth of the Constructivist movement in revolutionary Russia, which expressed in art and design the ideology of the Soviets. However, some believe, Melnikov would have baulked if he were to be described as a Constructivist.

By the early 1930’s Stalin’s iron grip stretched to state sponsored architecture, which meant the mass rejection of Constructivism. Design moved firmly in the direction of Social Realism, and by 1933 it had turned shunned the Avant-Garde. Yet Melnikov obstinately would not fall in with the new orthodoxy. In 1937 he was removed from the first All-Union Congress of Soviet Architects, which meant he could no longer practice.

Left in a desperate situation, Melnikov had no option but to withdraw from public life and work from his house as an artist and teacher. Conformity to the state’s vision of style and design meant Melnikov didn’t receive true acknowledgement as a giant of architecture until he was near death. In a long overdue acknowledgement of his importance, Melnikov was, in 1972, awarded the title Doctor of Architecture. Two years later he died.

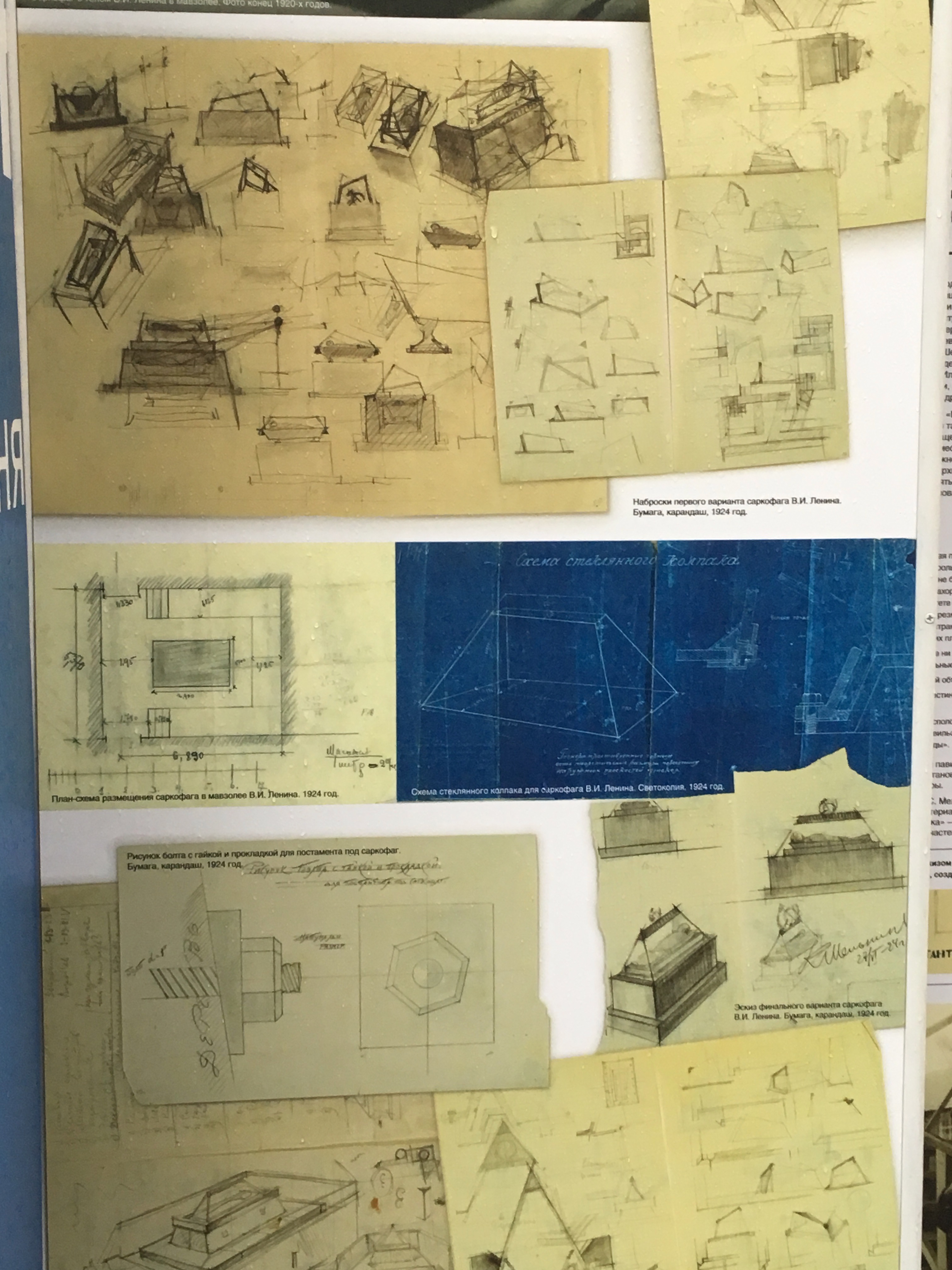

His son, Viktor, preserved the home and protected the archives that included Melnikov’s designs for Lenin’s sarcophagus. After Viktor’s death, the story of the house gets complicated.

The first impression a visitor has as they enter the house from Krivobatsky Lane is its size. Erected in a surprisingly narrow plot, it feels as if the buildings either side are pressing on its space.

What is clear is that it was built as an expression of Melnikov’s vision of family life. Mirroring his own childhood, he constructed a bedroom containing enough cots for the entire family, but in stark contrast to this austerity of personal space there lies an opulent rug brought back from Paris at the time of the 1925 International Exposition. One should remember that at that time, Russia was scoured by cruel famine.

The preservation of the house matters, Soviet Avant-Garde architecture in Russia is at constant risk and every building saved is a fragile reminder of how much is lost. How the house survived all these years, through all the turmoil and political change, is a mixture of luck, the devotion of Melnikov’s son Viktor and the determination of conservationists.

The Melnikov House is a recent recipient of a Getty Foundation grant for pre-conservation research.

Access to the interior is by appointment only, which makes sense because the contents are so delicate; a cup, a note, a photo, kitchen utensils, an easel. It seems near miraculous that this ephemera survived.