London’s Czech Embassy – Brutalist and Proud

Award-winning, brutalist, concrete, elegant, in profound contrast with the white stucco Italianate mansions around it, a juxtaposition so appropriate for a uniquely different country.

Notting Hill Gate, Czech Embassy

Next door to Prince William’s family home, Kensington Palace, running approximately south from Notting Hill Gate, Kensington Palace Gardens, is an 800 metre street of the very grandest buildings. It’s filled with embassies and billionaires’ homes. Nations with frosty diplomatic relations or none at all, neighbour each other. But on the corner, at the Notting Hill Gate end, is the Embassy of the Czech Republic, award-winning, brutalist, concrete, elegant, in profound contrast with the white stucco Italianate mansions around it, a juxtaposition so appropriate for a uniquely different country.

Greyscape had the pleasure of a tour conducted by Pavel Šembra of the Czech Centre and Michal Zilavsky, Third Secretary of the Embassy

Sixth floor, roof terrace of the Czech Embassy

Out of the horrors of the Great War, just weeks after the guns fell silent, the new nation of Czechoslovakia was created from a portion of the defunct Austro-Hungarian empire. The previous century had seen the aspirations of many peoples for self-determination growing and becoming insistent. Hence Czechoslovakia. It was a brand new democracy, industrious and sophisticated, that lasted until 1938 when it was sacrificed as an appeasement gift to Nazi Germany. The end of the Second World War brought Czechoslovakia into the communist orbit. In 1968 the Soviets brutally crushed the liberalising government of the country. When the Eastern bloc began to totter, the so-called Velvet Revolution ended Communist rule. But it was a close-run thing. The regime’s riot police had attacked demonstrating students but hundreds of thousands of courageous people filled the streets and the communist government resigned.

Garden view of the Czech Embassy

Rooftop, Czech Embassy

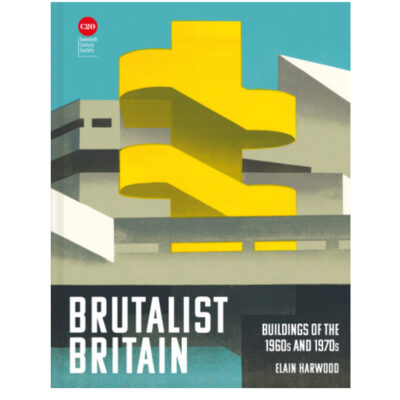

In 1965 a new Czechoslovak Embassy in London was built. It was designed by Jan Bočan, Jan Šrámek and Karel Štěpánský from the atelier Beta Prague Project Institute. They worked with a Scottish architect, Sir Robert Matthew, a modernist who played a major role in the construction of the Royal Festival Hall, an important part of the post-War reconstruction of London, before returning to his native Edinburgh to design a number of striking modernist developments. In the mid-60s Czechoslovakia had entered a golden age of architecture, confidently taking from the best of modernism and rejecting the intimidatory massives of socialist realism. Not just in London but Czechoslovakia was building across the world, embassies, trade missions and expos. The London embassy on that corner, the residential block stretching along Notting Hill High Street while the offices were built at right angles along Kensington Palace Gardens, was a statement in concrete about the exceptional nature of the nation.

Ground floor, the Czech Embassy

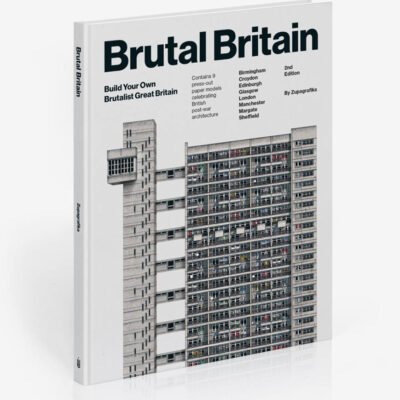

The embassy won the 1971 RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) Award for the best building in the United Kingdom created by foreign architects. It’s a purist brutalist design using precast concrete. Like the Barbican with its bush-hammered appearance, the finish is rough and shows the tool work.

1971 RIBA award for the Czech Embassy

In 1993 the Czech and Slovak components of the country separated into two new nations, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. Yet another peaceful transition. One can almost imagine all those other embassies along Kensignton Palace Gardens sideways eyeing the Czechs and the Slovaks with respect for managing their affairs without bloodshed.

Franta Belsky sculpture, Czech Embassy

But what were the Czechs and the Slovaks to do about their striking embassy buildings? Well, of course, in another civilised and peaceable decision, they divided the London embassy into two. The block on Notting Hill Gate becomes the Czech Embassy and the neighbouring office block becomes the Slovak Embassy.

The Czech block already had meeting rooms and offices and it has been further adapted to serve its new purpose. It still provides a variety of apartments for staff, something hugely welcome for the diplomats as the Embassy is located in a breathtakingly expensive part of London.

The Embassy of the Slovak Republic from the roof of the Czech Embassy

On five floors with a flat, accessible roof, the top floor has a communal dining area with an extensive kitchen now, mostly unused.

Dining room, top floor Czech Embassy

The floors below contain a large number of duplex flats. The ground and mezzanine floors comprise offices and conference rooms. The lower ground floor of the Czech Embassy has retained the auditorium, cinema room and the basement parking garage has been divided by a wall.

Reception room , ground floor Czech Embassy

The ground floor function room with beautiful views of the lawn behind the embassy contains works by the Czech-British sculptor Franta Belsky. He was the son of the famous Czech economist Joseph Belsky who, somewhat to his father’s chagrin, took up a career in art. But he was also a soldier, joining the Czech army in exile when Second World War broke out in September 1939. The Czech units that escaped from France after Dunkirk were based at Cholmondeley Park, Cheshire, where they were reviewed by Winston Churchill. Belsky recalled that when he was inspected by Churchill he made such an impression that he promised himself to one day sculpt the wartime leader.

Sir Winston Churchill by Franta Belsky

The embassy’s Czech Centre showcases the visual and performing arts, film, literature, music, architecture, design and fashion, science and social innovations. It presents its own programmes and also supports other intercultural initiatives among Czech and UK partners. Its podcast series presents some of Europe’s most talented and respected artists, performers and influencers. The former Director of the BBC World Service and the Barbican Centre, Sir John Tusa was among the guests.

Auditorium and cinema, Czech Embassy

View from the dining room of the Czech Embassy

But what of Czech architecture since the 60s and 70s? First, the London Embassy was far from being the only expression of brutalism in Czechoslovakia. Karel Hubáček’s television tower and hotel on Mount Ještěd remains a powerful design complemented by a bold interior.

The Jested Tower and Hotel ŠJů, Wikimedia Commons

Eva Jiřičná stands out as a contemporary Czech architect. Her bio tracks recent Czech history. She was born in the dark days immediately before the Nazi occupation of the Czechoslovak heartlands and she came of age as an architect while working in London as the Soviet Warsaw Pact crushed Dubček’s Czechoslovak government in 1968. There she remained because she wasn’t allowed back and developed a reputation as an architect and interior designer, cleverly deploying industrial materials in her work.

Czech architecture continues to innovate and invent, to flourish. The architecture reflects the vitality or otherwise of society and on that measure, the Czech Republic is continuing to show the energy and creativity of its people.

Website of the Embassy of the Czech Republic in London

Images other than the Jested Tower, Howard Morris