Very nearly called Lenin Court

Lubetkin’s Modernist Icon Bevin Court in the ‘Socialist Republic of Finsbury’

Bevin Court entrance

Bevin Court is a sought after London home in a Modernist icon designed by the enigmatic giant of architecture Berthold Lubetkin. It was very nearly called Lenin Court and there’s a secret buried under the striking central staircase.

An emigre, Berthold Lubetkin came to Britain in 1930. For many years his true origins were a mystery, even to his own family, for whom he laid a false trail of crumbs that led to a Tsarist admiral, Admiral Makarov, as his father. But that wasn’t the truth or anywhere remotely near the truth.

Of two things there’s no doubt; Lubetkin was a brilliant architect and, secondly, a committed communist. Both these key elements of his character brought him to the London Borough of Finsbury AKA the People’s Republic of Finsbury, and to Bevin Court.

Bevin Court courtesy of copyright owner Dr Rajiv Shah

In London Lubetkin established, with a group of new architects, the Tecton practice. This practice, working with the gifted engineer Ove Arup, went on to become the country’s leading architectural firm. With Walter Gropius, head of the Bauhaus, moving to London in 1934 and a number of its leading lights including Maholy-Nagy and Breuer, there was an all too brief flowering of avant garde architecture and intellectual thought, a desire to bring to the working class modern, healthy homes in harmony with nature informed by the socialist ideals of the circle. The Bauhaus in London coalesced around the Lawn Road Flats, the Isokon. Lubetkin was a member of MARS, the Modern Architecture Research Group, a group that included Wells Coates the designer of the Isokon. But Lubetkin and Gropius didn’t work together, barely encountered each other and they followed quite different paths to modernism.

Lubetkin and the Tecton had made a huge impact with the Gorilla House and then the Penguin House at London Zoo, Dudley Zoo followed by Highpoint in Highgate, Highpoint I and II, Modernist apartment blocks that were, perhaps curiously for such an uncompromising communist, luxurious and bourgeois.

The Penguin Pool in London Zoo, Regent’s Park ©

However, the next development fell four square with Lubetkin’s ideals and took him to the London Borough of Finsbury.

Bevin Court ground floor

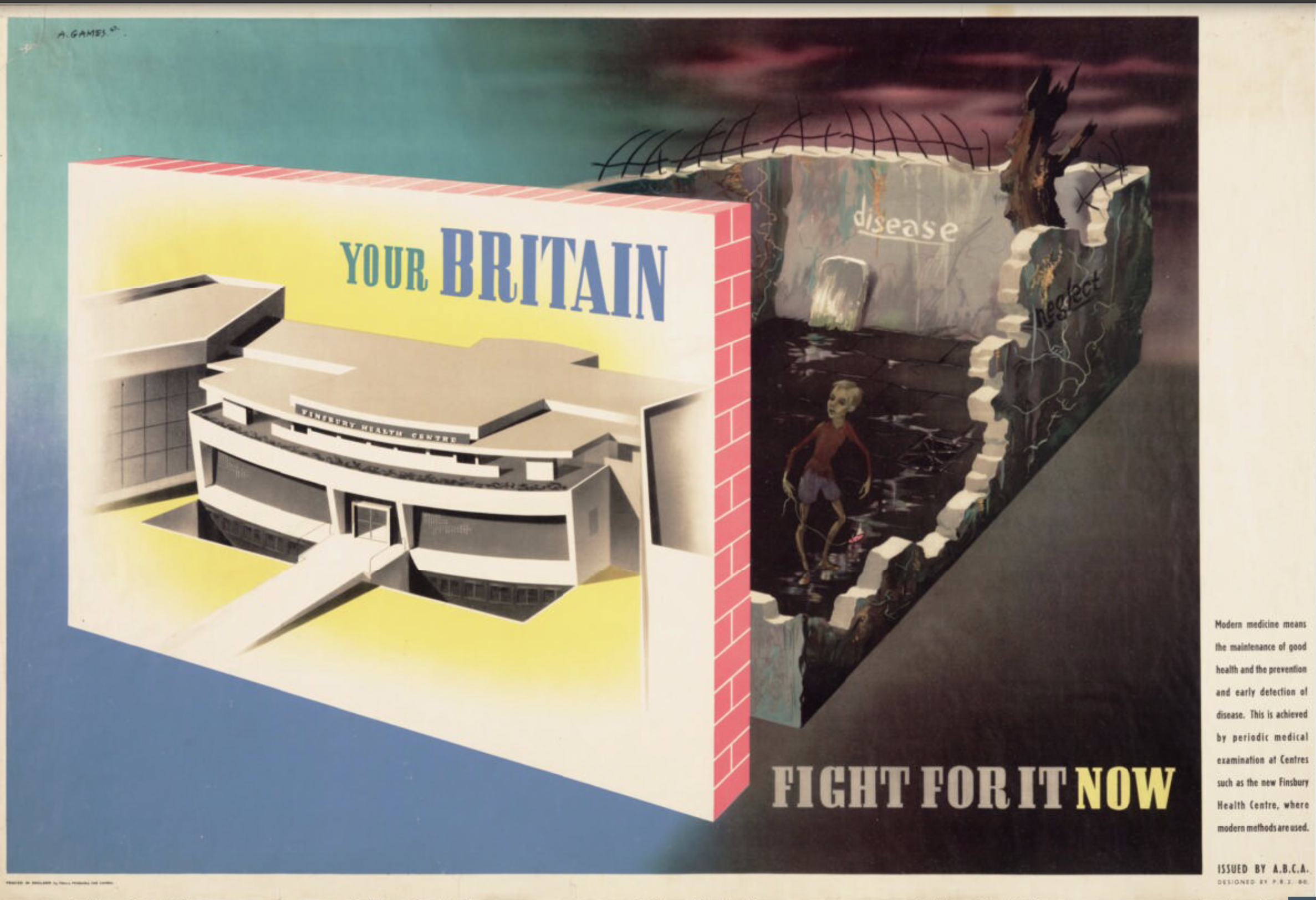

The Finsbury Health Centre is a beautiful Modernist design to provide for the physical and social health of ordinary people. It was a decade and a world war ahead of the National Health Service.

And then as war loomed, in 1939, Lubetkin gave up his business and social success and became a farmer, an occupation about which he knew nothing. He moved to a rundown farm and learned how to farm the hard way. His connections with London Zoo did mean that he cared for some rather exotic evacuee animals. For a time the farm received as guests intellectuals from Lubetkin’s circle but that seemed to be that.

When Germany invaded, the Soviet Union became the UK’s ally and Winston Churchill’s loathing of Communism gave way to his even more powerful hatred of Naziism and the UK made common cause with the USSR. Lubetkin was asked to return from the country and here there are competing accounts, one where he was commissioned by Finsbury Council and the other by the Russian Embassy in London to design and erect a monument to Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov who had lived at 30 Holford Square in Finsbury from 1902 to 1903. V. I. Ulyanov is better known to history as Lenin. There’s no irony in that he lived in Finsbury. It has always been a progressive part of London. The first ethnic Asian Member of Parliament was elected there, in 1892. In fact, as confirmed by John Allan, Lubetkin’s biographer, while Finsbury commissioned the monument the bust of Lenin was donated by the Soviet embassy.

British Pathé News 1942 ‘Lenin Memorial Unveiled’ courtesy of and copyright owned by British Pathé