Examining Unité d’Habitation in Nantes-Rezé

La Maison Radieuse Is The Perfect Introduction Into Le Corbusier’s Vision For City Planning

by Caroline Baron

Image: Laurent Etourneau ©

Can there be a more optimist name? La Maison Radieuse.

“Maison” like a giant house united under one single roof, built as a home for to up to 1500 residents; “Radieuse” like a radiant sun, omnipresent in Le Corbusier’s architectural work. The word symbolises more, it’s symbolic; an attempt to erase the atrocities of the Second World War (Nantes had been devastatingly bombed in 1943 and was described as a ville sinstree); a desire to put a smile on people’s faces by building homes that were equipped for a modern family and the community directly surrounding it. Because substituting individualism for the pleasure of living together was always on the architect’s agenda. And as much a sign of progress and modernity as a framework for happiness and well-being.

e

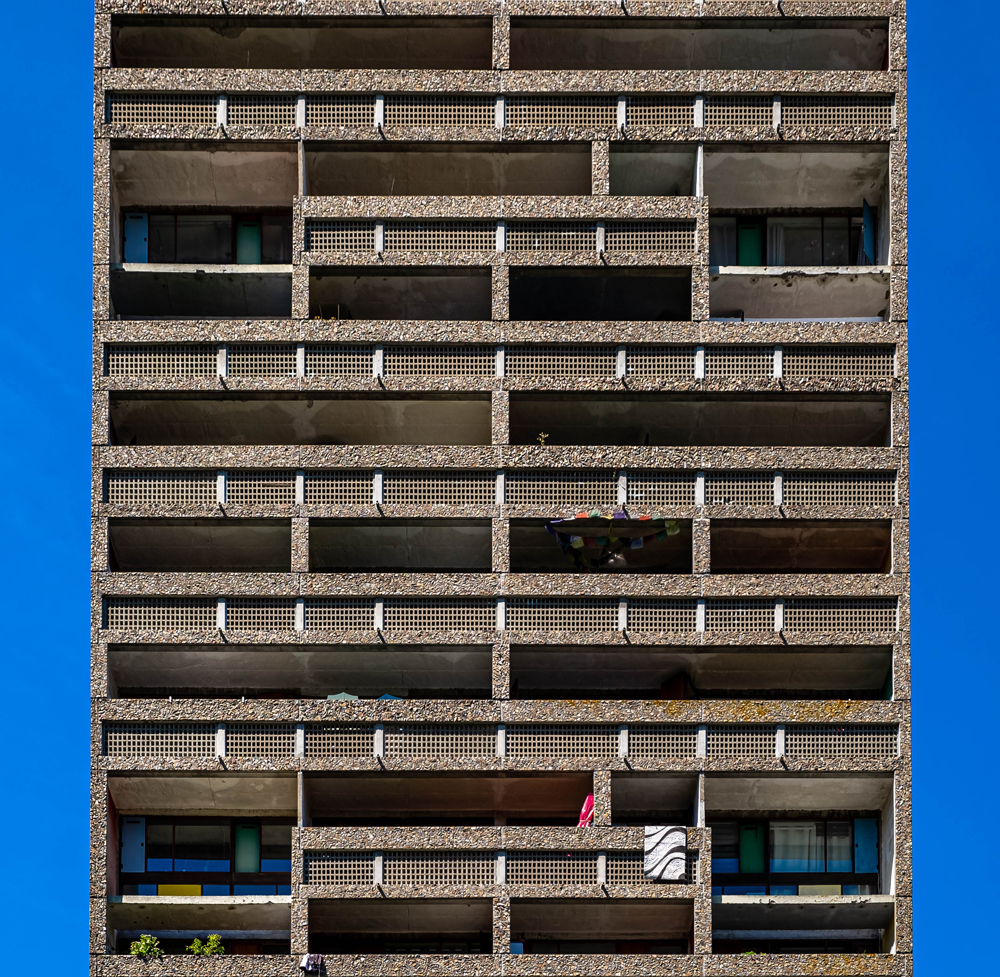

Balconies, La Maison Radieuse Image Laurent Etourneau ©

Yet there remain many pre-conceptions about brutalist architecture. One being how on earth can people be happy in those grey-highrise-squared-shaped buildings? A series of adjectives which, one after another, go against the common idea that round shapes are what naturally smoothes things over – “arrondir les angles” in French means making things good again – versus angular traits that tend to make things (look) harsher. Or perhaps it’s simply a more realistic, down-to-earth way of thinking about everyday life.

Image Caroline Baron

Things are rarely smooth in the world of mortals. If Gaudi was looking at colours and round shapes as a means to get closer to God, could Le Corbusier have been looking at hard angles as a way to be closer to humanity?

Construct the perfect family home to protect it. Or to quote the man himself in a letter to Gabriel Chéreau in 1955:

“I believe that the name Maison Radieuse works because what’s radiant about it are each of the households within it, meaning each family home. And with 300 family homes, Nantes has therefore 300 radiant households.”

La Maison Radieuse Nantes Rezé Image Laurent Etourneau ©

It really is about the project’s internal life, what’s going on on the inside that matters. Even I, a great fan of Brutalist architecture, have to admit it doesn’t look very “radiant” when I glimpse at it below as my plane passes over it when I return from London.

The sand, ‘sable’ used in “unités d’habitation” turns somewhat grey depending on its nature. The Mediterranean sand used in Marseille, for instance, is a lot whiter, which makes it more beaming and bright, and consequently less hostile.

Béton, La Maison Radieuse Image Laurent Etourneau ©

Grey can be intimidating if not a little scary – especially when one is presented with something hundred of metres long, fifty metres high and twenty metres in depth. In life in general, something grey never usually presages something good, does it? And yet, it is a neutral colour; goes with everything; blends in; mixes with pretty much any colours, in the case of La Maison Radieuse allowing the musicality of its colourful windows to operate, a sign of the joy emanating from each balcony – each radiant household – rather than the structure itself. Grey is what allows them to blend into one another in the spirit of the community it is carrying, like a “vertical village”.

A Vertical Village

Through the concept of “vertical village” and “streets in the sky” – which in passing was also championed by architects such as Erno Goldfinger and the Smithsons, Corbusier wanted to gather enough residents within a single volume in order to allow collective life to flourish. There was the issue of critical mass to allow the indispensable shops to remain profitable and for the creation of a school.

I thought a lot about this structure when we went into lockdown. Being geographically close, confined in my parents’ home, I realised how Le Corbusier’s thinking – answering the need to be self-sufficient and together at the same time works just as effectively today. People contained in small familial units within a bigger unit. A space providing essential things only: food and education, is incredibly apt for our times regardless that the project was conceived more than half a century ago. Was its conception something of a hangover from the Second World War?

La Maison Radieuse Image Laurent Etourneau ©

Visitors to La Maison Radieuse, (there are guided tours organised by the city of Rezé) will find it in good shape, exuding a feeling of well-being. Regardless that certain amenities such as food shopping, reception and post-service have now disappeared, the local school is still welcoming the children of residents.

Original 1955 Features

You can step back to 1955 and visit a flat which still has all the original features, the kitchen and living room are intact, all the way up to the bedrooms and bathrooms designed by the French architect Charlotte Perriand who worked closely with Le Corbusier throughout her life and was in charge of the interior equipment of the unités.

La Maison Radieuse Corbusier Image Caroline Baron

Photo: Herve Moine CC BY SA 3.0

Image Caroline Baron

As a lover of Brutalist and Modernist architecture, I am lucky to have grown up close to one of his unité d’habitation in Rezé. Still, I wish I could talk more from an insider’s perspective and not have to experience it like a visitor buying a ticket to visit a museum.

Shining a positive light

As the situation evolves it may be that I’ll be here in France for the whole of the summer and that will present an opportunity to immerse myself in La Maison Radieuse’s communal life. Maybe in the aftermath of lockdown, I can get a proper look at what is left of the original concept after seventy years. I am optimistic that I might be able to shine a positive light on the often-negative association’s people bring to social housing; celebrate the diversity within, or perhaps reveal that sadly the intentions of its creators are all but lost.

Either way, I can simply answer the nagging question: does something remain of the original optimistic idea and ideal, behind the dark grey block of concrete and faded colourful windows?

La Maison Radieuse Modular Man Corbusier Image Laurent Etourneau

About Caroline Baron:

Caroline, originally from Paris has been living in London for 10 years. She works in advertising as a strategist. Her spare time is spent interviewing people who live in modernist and brutalist estates for her podcast and blog. Caroline is interested in the social aspect of architecture and how it affects, enriches people’s lives. She studied interior design a little in Florence and hopes to renovate and run her own guesthouse in France in the not too distant future.

Read Caroline’s blog: Residentsonly

Greyscape was delighted to feature in an episode of Caroline’s podcast featuring people living in iconic 20th Century buildings: The Barbican

We Asked:

It’s famous for the butter biscuit «Petit Beurre» by the brand LU. The original factory, on the outskirts of Nantes still carries its iconic logo, the rest of the complex has been destroyed.

So many! I went for one slow and one upbeat… all about love of course:)« La déclaration d’amour » by France Galle« On va s’aimer » by Gilbert Montagné

My hero is Charlotte Perriand (as a woman and as an architect)

My favourite interior design book is an old one by Habitat: « Aimer sa maison » by Tamsin Blanchard. It’s something about how a space makes you feel that I’ve taken away with me ever since. I always come back to this book.

Caroline on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/residentsonly_/