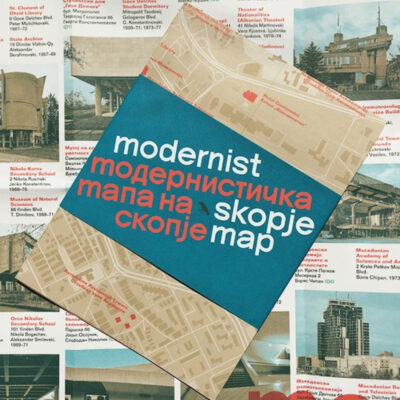

How an earthquake brought Kenzo Tange to Skopje

Post Office and Telecomunications Centre, Architect Janko Konstantinov, image Sam Leijenhorst

Kenzo Tange had already proved himself as the architect to enable the ancient city of Skopje to rise like a phoenix from the ashes. His rebuilding of post-war Hiroshima had been widely praised. When Skopje almost disappeared under the weight of a devastating 6.1 magnitude earthquake on the morning of 26th July 1963, it was very quickly clear that a masterplan for the city would be needed, an organised carefully thought out response to the natural disaster.

Post Office and Telecommunications Centre

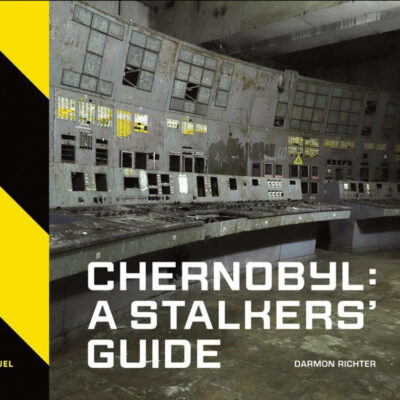

The earthquake in a region used to seismic activity left more than 2000 men, women and children dead and several thousand injured. One of the earliest foreign journalists to arrive in the stricken city recalled it looking more like a victim of a bombing campaign.

Josip Tito leads a delegation in Ivo Lola Ribar St (State Archives DARM)

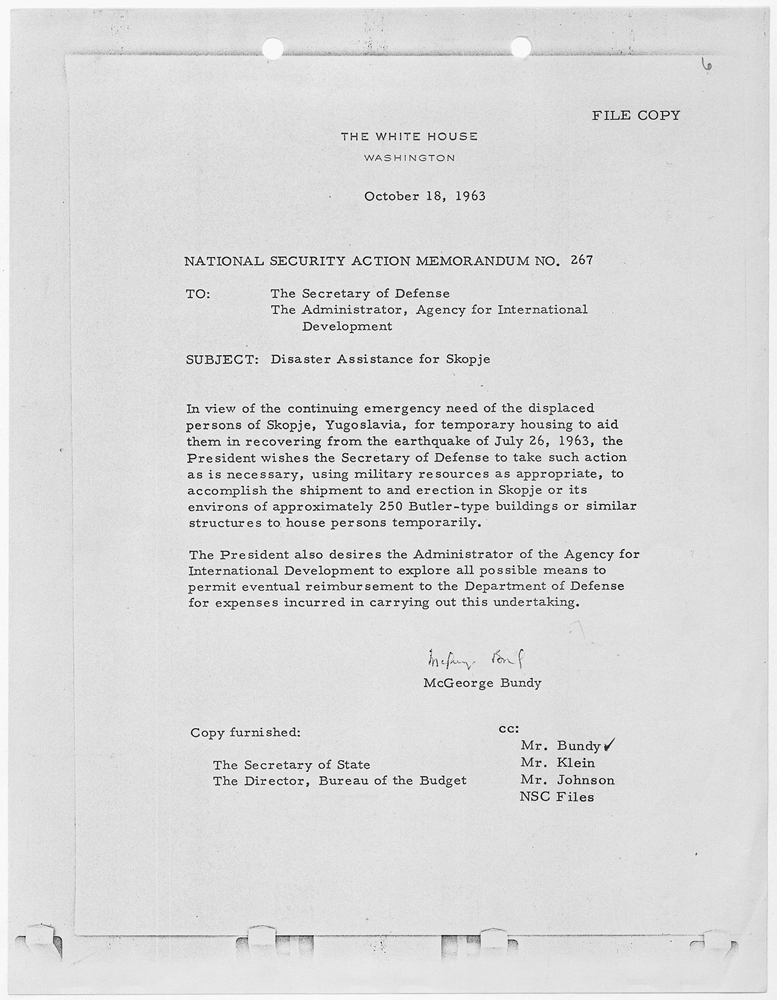

These events, at a time when television was becoming the dominant news medium, was shown on television and Pathé News in cinemas worldwide. The almost destruction of Skopje caught the world’s attention. Josip Tito’s communist Yugoslav government was flooded with offers of know-how and international aid from 78 countries. Field hospitals and temporary homes were set up for the more than 150,000 people who were made homeless.

The day after, citizens preparing temporary dwellings (Image State Archive DARM)

National Security Action Memorandum No. 267 Disaster Assistance for Skopje

A year later there were still huge numbers living in poor conditions, many still in tented cities and prefabricated temporary homes and it was now clear was that much of the infrastructure was beyond repair.

Post Office and Telecommunications Centre

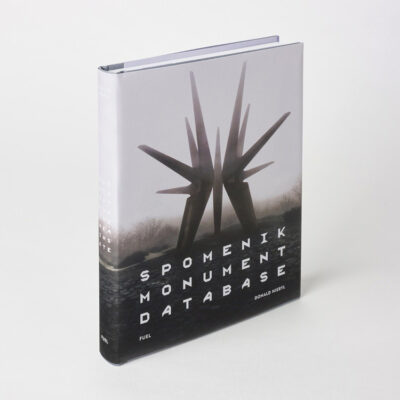

The UN with UNESCO funded an invitee-only international competition to create the Masterplan for Skopje. It is that plan that almost 60 years later brought photographer, videographer and creator of Long Way to Tokyo, Sam Leijenhorst to the city. How often does one get the opportunity to experience a city outside Japan with revered Japanese architect Kenzo Tange’s fingerprints all over it? The creation of a project in 1963, the year when world politics seemed to be spiralling out of control; the Cold War, the assassination of JFK, Reverend Martin Luther King Jnr leading the March on Washington and the Cuban missile crisis. In Skopje, there was an opportunity for meaningful visible humanitarian cooperation between East and West. Skopje remains endlessly fascinating to fans of architecture, reimagined twice, first in 1965 and again in 2014, by then the capital of the Republic of Northern Macedonia.

Post Office and Communications Centre

The lakeside city of Ohrid hosted, in 1964, the relief committee formed within weeks of the disaster. Representatives of the Yugoslav government and international experts came together to create a plan to rebuild the devestated city. Doxiadis Associates were named the contractor of the project. The UN together with Tito’s government named Adolf Ciborowski who had overseen the reconstruction of Warsaw, to supervise the rebuilding together with Stanislaw Janowski. By the end of the year, a plan was in place.

Image Dan CC BY SA 2.0

Goce Delčev Student Accommodation, Architect Georgi Konstantinovski Image Tashoskim CC BY SA 3.0

Moving quickly the competition to create the Masterplan for Skopje was opened exclusively to four international and four Yugoslavian firms early in 1965. Kenzo Tange’s design won and the runners up were Yugoslav architects Radovan Mischevik and Fedor Wenzler. The plan was agreed formally on the 16th November 1965. It didn’t play out as simply as perhaps had been hoped but ultimately the design teams came together, Tange was allocated 60% of the prize money and the local architects 40% from the UN Special Fund. A stellar lineup of architects and urban planners including Jaap Bakema and Janko Konstantinov worked on the project which took almost 25 years to complete. The second reconstruction project took place in 2014, after independence.

Porta Macedonia 2012

Sam Leijenhorst’s photos are from 2020 of a city which is now changing at a breakneck speed. The second renovation of Skopje in 2014 has been seen by some as a deliberate attempt to insert into the architecture of the city a historical narrative. Sam observes that it mixes with the brutalist architecture ‘neoclassical buildings to reflect the ancient Macedonian connections. These two (styles) now overlap one another, making for an interesting hybrid city’.

Alexander the Great, Macedonia Square Skopje Image Sam Leijenhorst

Museum of the Macedonian Struggle and National Theatre image Pudelek CC BY SA 4.0

All images and video are the copyright of Sam Leijenhorst © unless otherwise noted