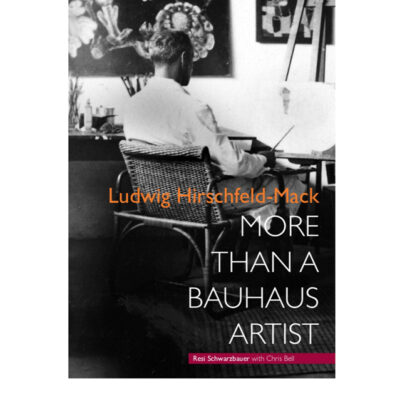

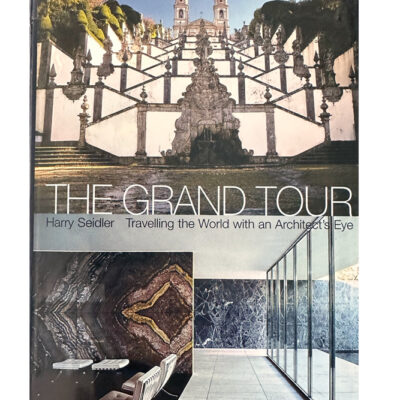

Harry Seidler, the Man Who Shaped Modernism

What was it that set Harry Seidler on course for his stellar career?

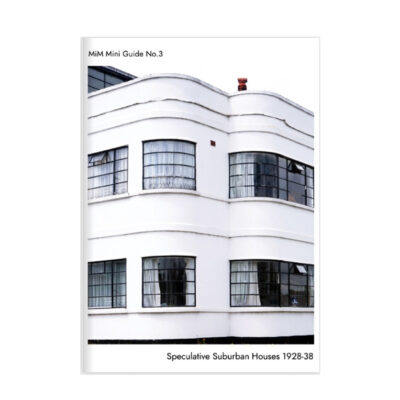

St Martins Place, Sydney Image Mike Oliver

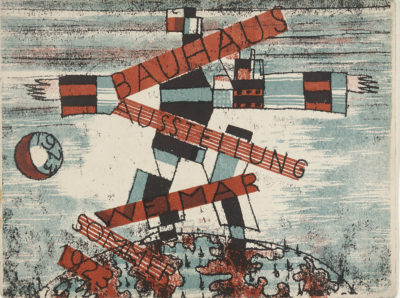

Born in 1923, so we’ve reached the centenary of Harry Seidler’s birth, which also happens to be the year Corbusier published Vers une Architecture – Towards a New Architecture, it’s a full blown challenge trying to figure out Harry. The expression, ‘a man of contradictions,’ is apt. We’ll start arguments if we try and list all the giants of Modernism, but alongside Corbusier, Gropius and Mies van de Rohe, must be Seidler. Just look at his output, the quality and originality of his designs and their profound influence on other architects down the years.

The moment he stepped foot in Australia, Seidler made his mark and just kept doing it for decade after decade. Winning the coveted Sir John Sulman Award in Australia in 1951 for Rose Seidler House brought him to national attention. Significantly Seidler said of criticism of one of his buildings:

‘It doesn’t worry me that people have criticised the building’

Were his focus and appetite for creativity derived from coping mechanisms forged by his experience of intense racial hatred and his departure from Vienna to England as a 15-year-old child, his subsequent internment by the British. Was it that trauma that gave Seidler a life-long resilience and a propensity for being unnecessarily blunt?

In 1938, the Anschluss, the merger of Austria into Germany made clear that the status of Jewish Austrians was increasingly precarious. Ubiquitous and growing hatred of Jews, now endorsed by and official government policy, prompted Harry Seidler’s family to get him out of the country to join his brother Marcell in England. Enrolled at the Cambridgeshire Technical School, the plan for a safe haven was derailed in 1939 when war broke out. By now classed an adult and an Enemy Alien, regardless that he was clearly not a threat, Harry together with his brother, were interned first in Liverpool and later on the Isle of Man with all the other German and Austrian nationals, irrespective of whether they were Nazis or the Jewish objects of their race hate. The brothers were then despatched, by boat, with other enemy aliens, to Canada. Once again the marginal hold that these boys had on ordinary life was ripped away. They were refugees regarded as barely better than enemy combatants. They came from a family of refugees. Harry and Marcel’s grandfather had been a Romanian timber cutter and made his way to Vienna. There his son, Harry’s father, for a while made a living selling textiles. But this was no more than interlude. Today the trauma of Sediler’s experiences is better understood. The diary Harry kept during this difficult period of great uncertainty has contributed to our understanding. A combination of words and images, the diary is kept in the State Library of New South Wales.

Rose Seidler House architect Harry Seidler Image Rory Hyde CC BY SA 2.0

A welcome change in understanding of the plight of this group of refugees came when the British Government adjusted their status to Friendly Alien. This allowed Seidler to study architecture at the University of Manitoba where his brilliance was clear. He won a scholarship to Harvard in 1946 to study under Gropius and Breuer and took summer courses at the Black Mountain School of Art. In this rarified atmosphere, his contemporaries included IM Pei & Paul Rudolph. Harry became Marcel Breuers’ chief assistant in his New York Office from 1946-48.

Travelling via Brazil, where he briefly worked for Niemeyer, Harry emigrated to Australia in 1948 to reunite with his parents who had arrived in ‘46. and at the age of 25 was commissioned by them to build their first home in the Sydney suburb of Wahroonga.

‘the most talked about house in Sydney’

Completed in 1950, Rose Seidler House became the ‘most talked about house in Sydney’, and was an immediate success. This was a game changer for Australian architecture. Harry built two other houses on the same site beside Ku-ring-gai National Park, the Marcus Seidler House (49-51) and the Julian Rose House (1950). Walter Gropius visited the house in 1954 and Eero Saarinen in 1956.

Harry and Penelope Seidler House Kalang Avenue CC BY 3.0 Image Sardaka

the ‘Seidlerisation of Sydney’

Informed by his time at Harvard, the work of Corbusier, Josef Albers, Breuer et al, Harry Seidler introduced his brand of modernism to Australia. But what did he think of Australia? In a 2002 interview speaking (not too fondly) of his adopted home he commented “There’s nobody and nothing here that sends the blood pressure up. It’s a backwater; a provincial dump in terms of the built environment.” Actually there is ample evidence of Harry’s real love for Australia and fellow Australians, but was this a marker of Harry’s worldview? Was it an acknowledgement that he was not getting the international name recognition that he clearly deserved and that folks like his old boss, Breuer got because he was so far away from the USA and Europe?

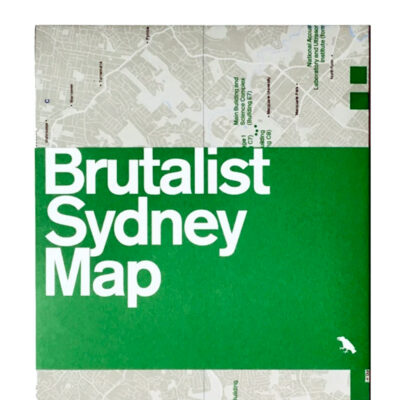

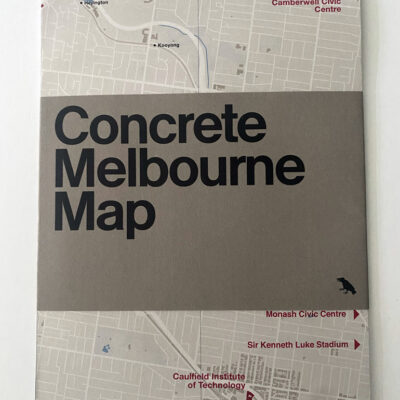

Australia House Image Duncan Gibbs

In 1960 Harry worked together with Italian structural engineer Pier Luigi Nervi on the Australia Square project, a retail and office complex in the heart of Sydney’s business district with, according to the Australian Institute of Architects, ‘the tallest lightweight concrete building in the world at the time it was built’*. European modernism often informed Harry’s thinking. His 1966 Arlington Apartments nodded to a design system not seen in Australia, originally created by Le Corbusier for L’Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, translated by Seidler, he made it his own. Major commissions throughout the ’60s and ’70s included the magnificent brutalist Australian Embassy in Paris designed in collaboration with Breuer.

Australian Embassy in Paris, Architects Harry Seidler with Marcel Breuer Image Howard Morris

Australian Embassy in Paris, Architects Harry Seidler with Marcel Breuer Image Howard Morris

‘Good design doesn’t date’

Seidler had a vision and the vision was uncompromising. It’s no surprise and nor is it inappropriate that he called himself the ‘torchbearer of Modernist architecture’. Here was an architect receiving both plaudits and opposition, who left his mark on the Sydney cityscape and never ever backed off of saying what he thought. He was never afraid to challenge at the highest level.

Harry wasn’t comfortable with his background. This prodigious talent, living physically and culturally far from where he was raised in the societal margins of pre-War Vienna, devised for himself a fairytale backstory. He was of noble descent, claimed Seidler. When in 2001 his biographer uncovered that Harry was the grandson of Carpathian timber cutter, he tried to get the reference removed from the book. Many Modernist talents had to flee the Nazis. Goldfinger was at ease with his origins but Seidler wasn’t. Erich Mendlesohn was OK with his history but Berthold Lubetkin, the great Modernist architect who settled in the UK, described himself as the illegitimate son of White Russian admiral when in fact he was from a Polish Jewish family murdered in the Holocaust. If one’s origins are humble, if they marked one for persecution and, let’s face it, death, why not become someone else. Of course what we have to wonder is if Seidler and Lubetkin hadn’t had the experiences they did, would they have been just as creative?

In his obituary, the art critic Robert Hughes complained about the ‘Seidlerisation of Sydney’, Harry would surely take that as a compliment.

Australia House Interior Image Duncan Gibbs