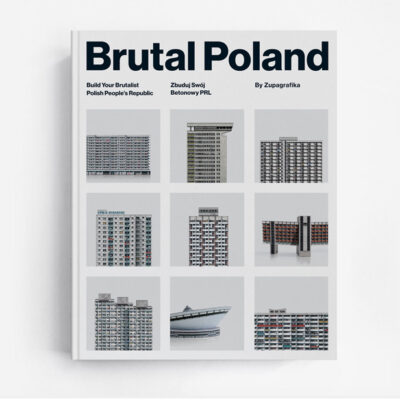

Bloki: Poland’s Architecture Journey Through Communism

From interwar years Modernism to communist bloki through a photographers lens

Artur Bednarczyk is a Warsaw native, born and bred, by day a mechanical production engineer with a second strand career as a photographer. He has a strong sense of his place in 20th-century post-communist era Poland. His passion is photographing modernist architecture, recording its presence, in the hope of ensuring the buildings are captured for posterity in a fast-changing urban landscape. Of equal interest are the blok districts, the bloki dzielnica.

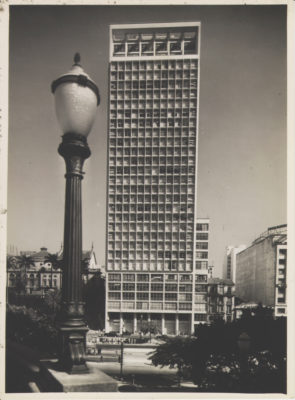

Manhattan Apartments Lodz Image Artur Bednarczyk ©

He shares about the remnants of Soviet architecture still evident in Poland;

‘My generation of Poles consider themselves lucky to have not lived through the communist era and to have avoided experiencing the atrocities of that oppressive regime, I can look at the buildings without the terrible aftertaste that comes with thinking about that era and all that happened, whereas for some older people the architecture acts as simply a reminder, a trigger to reflect about the past’

The Communist era in Poland which began in 1944 and ended forty-five years later in 1989, is remembered as a time when freedom of speech and culture was restricted, and the economy was severely impacted by Soviet economic policies. The dark underbelly of the regime was played out in a series of political murders, such as the 1970 Gdynia massacre when forty people were killed by the Polish army and the 1984 murder of Catholic priest Jerzy Popiełuszko who was one of the leaders of Solidarity, the Polish labour Union of the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk, which would not allow itself to be controlled by the Communist Party.

Today Poland is a free and democratic state fully immersed in the European Union and with a clear link from the past to the present, Donald Tusk embodies that connection, he was born in Gdansk, a founder of the Student Committee of Solidary, later became Prime Minister of Poland and is the current President of the EU.

Manhattan Appartments Lodz

Artur describes Gdansk’s block districts, bloki dzielnica, places with names such as Zabianka, Zaspa, Nowy Port and Przymorze.

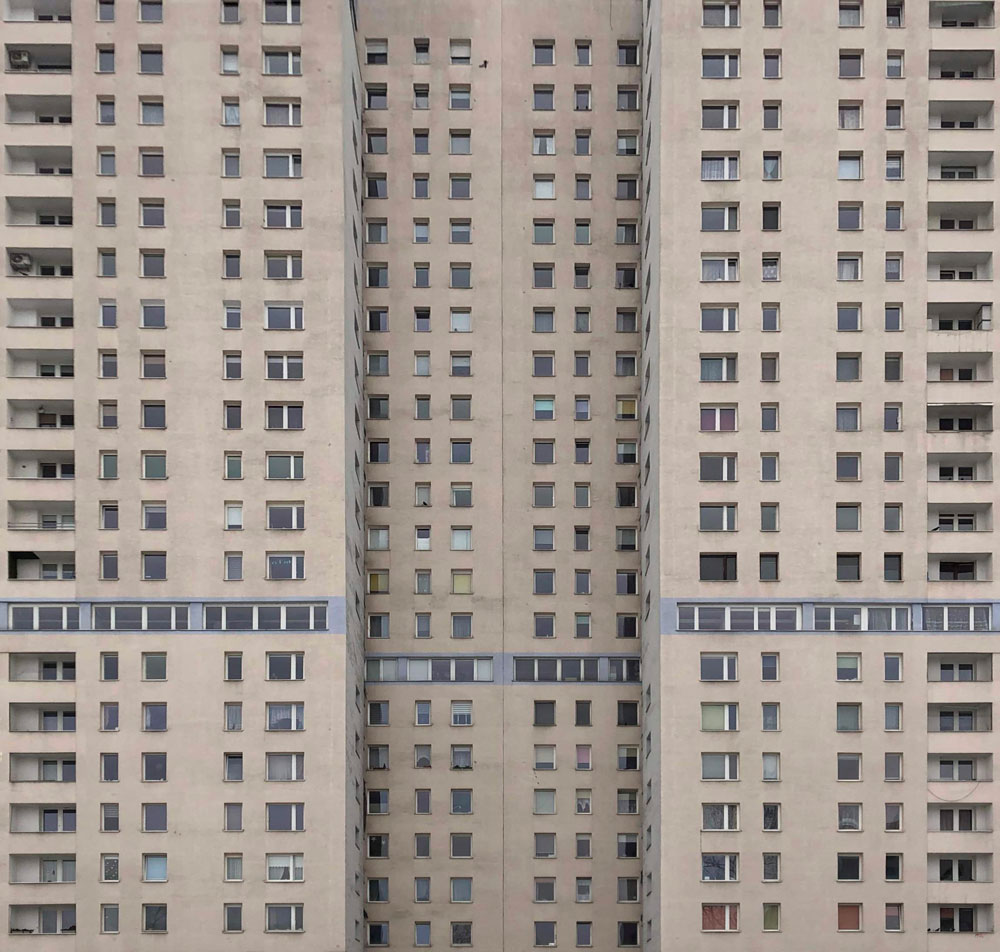

‘ These bloki stand as silent witnesses to the communist era, to key moments in recent Polish history, for example, the introduction of martial law in 1981, the Solidarity workers’ protests in 1970, 1976 and 1980. Later these same bloki were home to the same people who were key drivers in the reestablishing of democracy in Poland. The sadness as someone who appreciates and is interested in this architecture is that I am in a minority, not enough Poles truly understand or appreciate their beauty. Every time I take a picture of a béton flat I ask myself whether it might be the last chance to do so. I am beginning to see myself as a recorder of social history. Taking photos of old blocks of flats. Behind every façade or block is a very Polish human story’

Whilst the literal translation of bloki is perfectly obvious, its colloquial meaning is much deeper than simply shorthand for largescale residential accommodation. Thrown up after WW2 in answer to an acute housing shortage, putting people in bloki style mass housing ‘blokowisko’ was another building block for communists to achieve their ultimate, aim to control huge swathes of people.

Katowice Superjednostka

Arthur notes

‘What should be credited is the solving of a housing problem Before World War II almost every house was congested. The Communists built millions of new homes allowing people to live in a more civilized way. They were well thought out. Look at the urban layout and the carefully calibrated distances between buildings maximizing green space. Facilities such as schools and shops were built in close proximity. Originally painted grey which is hard to imagine today as so many have been highly adorned with coloured polystyrene installations which simply ruin the original aesthetic’ ‘The added concern for conservationists today is the fate of buildings such as the Emilia furniture house and the 1962 ‘Supersam’ modernist supermarket should sound warning alarms to conservationists and urban fans’

Katowice Kukurydze Ears of Corn Apartment Blok

Interestingly the 1960s bloki were not the first in Poland, modernists began building them in the interwar years but simply not on such a large scale. The 1929 Józega Montwilla-Mirecki modernist estate, in Polish an Osiedle was built in Lódź in 1929. Had the war not happened stopping everything in Poland in its tracks and the modernists had been free to continue to experiment it’s interesting to speculate about what might have happened and how different the landscape would have been. Too many of Poland’s finest modernist architects did not survive the war along with the visionaries who hired them.

Artur is a big fan of the Polish modernist dream city of Gdynia, a place that captures the spirit of an optimistic Poland entering what we now know to be the interwar years but was, in 1921, a new city in a newly liberated country. The city’s history in the intervening years goes from a creative blossoming into a painful period. Today once again its beautiful architecture is gaining a new following. Artur explains eloquently what it is that appeals to him so much about Polish interwar years modernism in Gdynia

‘it’s the lightness of their structure, brightly coloured facades and particularly beautifully rounded corners integral to the designs of so many of the villas and their sense of beauty in simplicity’

So long has passed since they were built and one of the curious problems in Poland is that there is not enough name recognition of the original modernist architects working across the country which begs the question, how did this come about? Across the border young Germans are certainly familiar with their local star architects, who rose to prominence in the aftermath of WW1. Are their familiarity and ability to name check more about the enduring power of the Bauhaus movement, Der Ring and the Deutscher Werkbund and how well those movements and associations have has been documented and remembered? The Polish contribution to design and architecture is breathtaking with people such as Henryk Berlewi, Lucien Corngold, Artur Tanikowski, Arieh Streimer, Josef Neufeld and Arieh Sharon, all Poles.

If you fancy getting outside the bubble of Warsaw keep an eye on Artur Instagram as he frequently travels outside the centre of the city on photo expeditions exploring dzielnica, ‘districts’ and modernist gems.

Greyscape’s photo tour with Artur

Gdansk

Gdansk Przymorze District

Gdansk Przymorze District

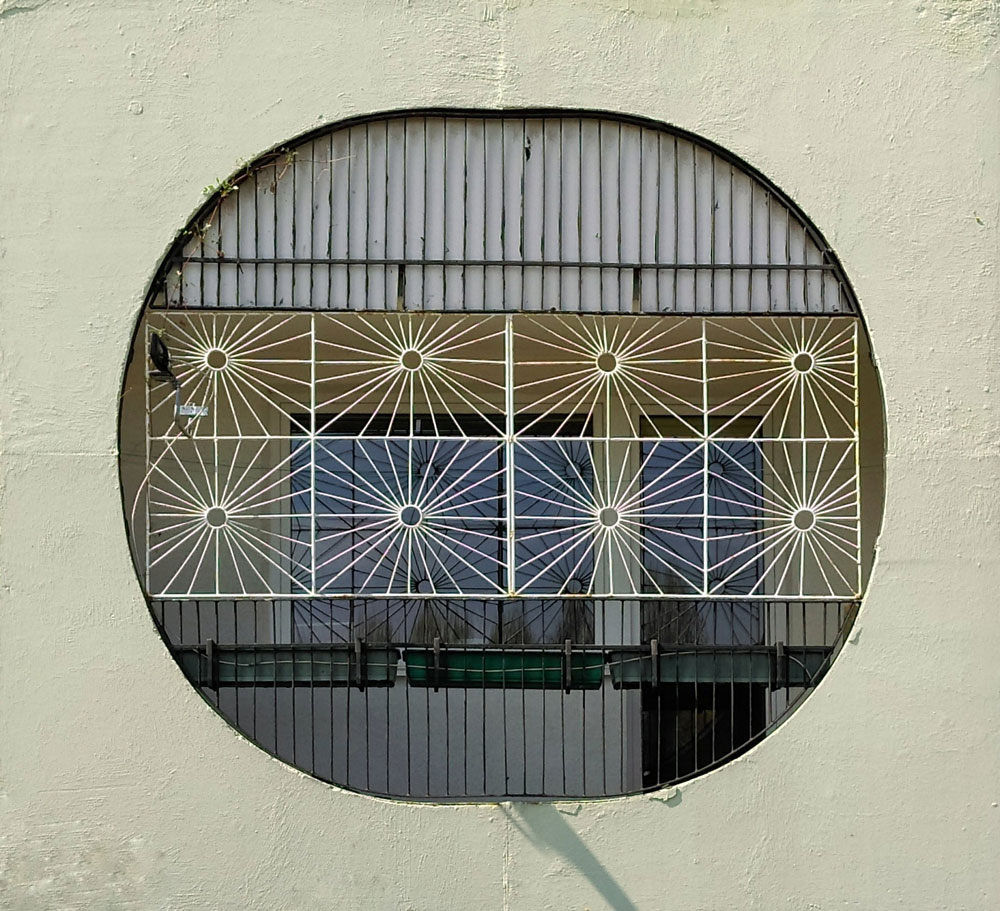

‘This picture was taken in the district of Gdańsk where Lech Walesa lived in the 1980s during the Solidarity strikes. As you have probably noticed the shape of the balcony captured in the photo is quite similar to an old television set. Residents could literally look over their balconies and watch history unfold below them. Sadly they are somewhat underrated at the moment’

Poznań

‘That moment when you realise that you have arrived too late to see one of the few remaining ‘raw’ looking brutalist estates. To my horror, I discovered that it had now turned into a two-tone pastel-colour painted block of flats. To be honest I’m still glad I managed to still get a sense of what they would have been like in their original untouched form, which didn’t fail to startle me. The solid structure and the vastness of the concrete reminded me how each blok was planned to be, a neutral unit designed to fit in as many people as possible. Despite that, it didn’t stay that neutral for long. You can sense that there are many stories hidden from view and the only clue is the differing curtains!’

Kraków

Hotel Forum Krakow

Hotel Forum Krakow

The 1980s ‘Forum’ hotel is what I consider Poland’s symbol of disillusion. It’s history perfectly captures the spirit of the times of the transformation that took place after the fall of the Iron Curtain. The hotel was one of the most original and futuristic buildings in Europe. Its bold design and newly-introduced innovations made it the most luxurious, ‘western standard’ desirable place for wealthy people in Poland. The mindset at the time was to show that Poland was more than capable of catching up with the progressive West. Unfortunately, the glorious days of the ‘Forum’ hotel were limited, no one knows the precise reason for the hotel’s downfall which to this day remains a mystery, what was clear was that the hotel’s closure was rather abrupt. To this day the building serves as a structure upon which hangs a huge advertising banner. Behind the banner are beautiful windows and details and the empty skeleton of a building that used to be a promising and lively local landmark.

We asked:

Must-see building in your home town Warsaw? The Palace of Culture and Science

Best Bar? Jaś i Małgosia (al. Jana Pawła II 57)- one of the most iconic places in Warsaw.

Best photo we have to take? Za Żelazną Bramą Estate- communist era blok of flats today surrounded by postmodernist skyscrapers

Best museum? The National Museum in Warsaw

Polish expression we should all know? Na zdrowie! (cheers)

Best Polish dish we all have to try? Pierogi

Which Polish architects do you most think should be remembered?

Oskar and Zofia Hansen who created the theory of Open Form. You can see the fruits of their ideas in Szumin (70 km from Warsaw), which was their home town and in Przyczółek Grochowski, which also happens to be home to the longest building in Poland.

An important Warsaw resident we should all be familiar with? Marie Curie

Your favorite film? Amadeus by Milos Forman

If you could photograph one building anywhere in the world where would that be?

Marina City in Chicago. It had a significant influence on the history of architecture.

Poznan Zegrze Bloki Dzielnica Image Artur Bednarczyk ©

Poznan Zegrze Bloki Dzielnica Image Artur Bednarczyk ©

Follow Artur on Instagram www.instagram.com/arczi.bednarczi

Check out his photo used by the National Institute of Architecture and Urban Planning

All images are Copyright of Artur Bednarczyk