Nakagin Capsule Tower

By Greyscape

5th September 2018

Think tiny capsules plugged into a tower where you can reach everything by more or less a stretch of the arm or by stepping a few paces back and forth. Alternatively, imagine a home where there is no place to hide, that is in essence what it must feel like living in one of Kisho Kurokawa’s capsules within the Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Designed to accommodate Monday to Friday ‘salarymen’ whose commute would be too far, each of the 132 capsules was designed to accommodate bed, bath and not much beyond. In 1972, this new building optimistically pointed the way forward to a new sustainable, recyclable future care of a 300-square-foot pod, which curiously is the same area size as a traditional Japanese tea ceremony room. Each unit was designed to be plugged in and theoretically pulled out of one of the two central cores.

Japanese Metabolist Movement

It’s hard to grasp just how excited everyone was about the new capsule tower, an organic building deemed a perfect example of the Japanese Metabolist movement created by one of the movement’s founding members. The Metabolist movement manifesto was delivered in 1960, but it took almost a decade to put it into practice at Osaka’s Expo70. Kurokawa’s Capsule House was showcased in the Theme Pavilion as future housing. ‘The house was suspended from a space frame into the pavilion built with a window in the living room floor to view the ground below’

The Future of Architecture

He translated that into Nakagin Capsule Tower two years later, and the press loved it. This was a real example of the future of architecture. Sadly, the idea did not act as a trigger for similar projects. Criticism of the building included the fact that the only organic element was in the hands of the architect, the tenants could change nothing. The building then suffered from a serious asbestos problem, which meant the shutting down of the air conditioning system, and there were some major issues with the water supply, causing tenants to abandon their baths and use a shared shower unit located elsewhere in the building.

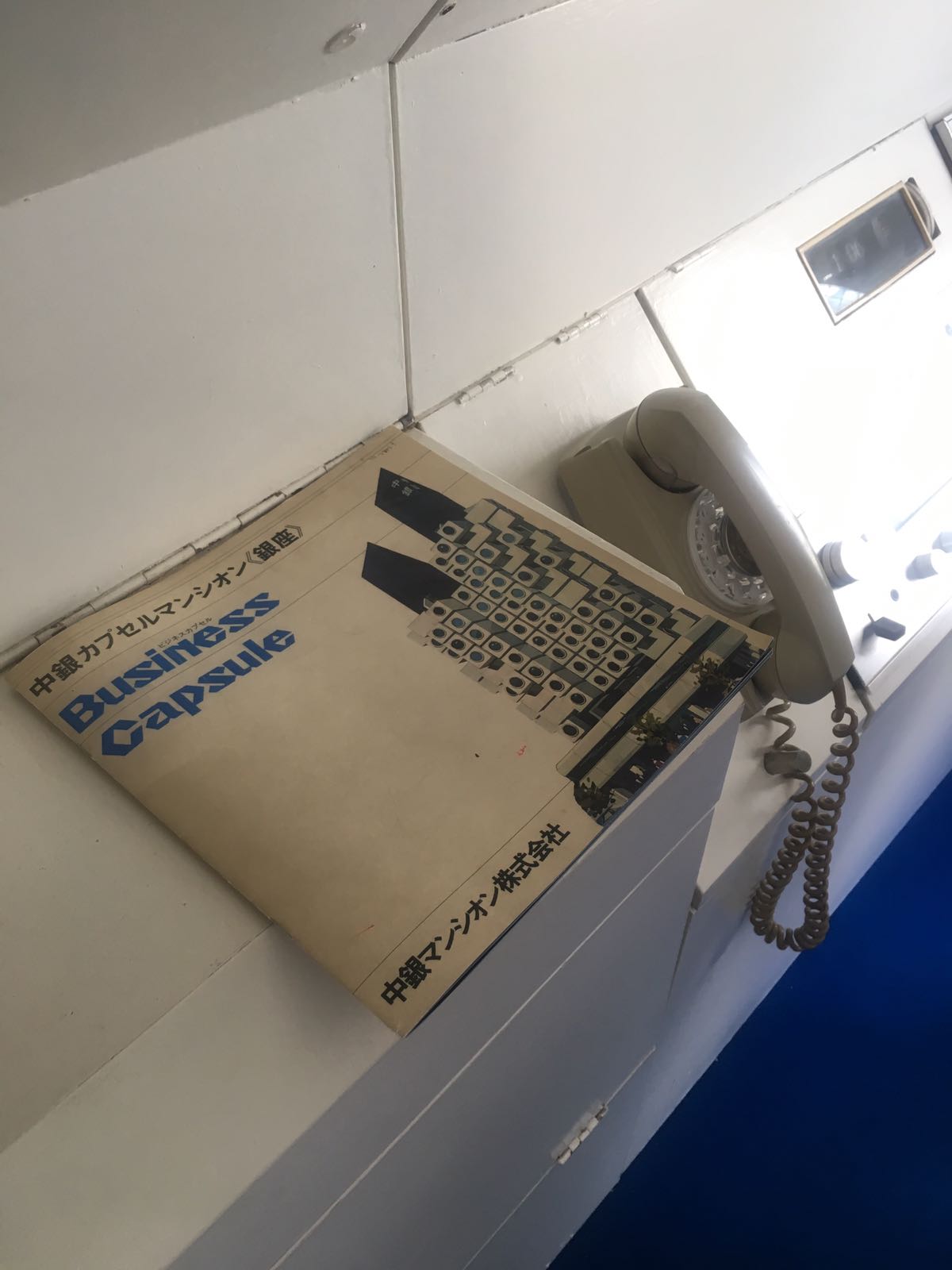

While there is a litany of problems, there is also a fabulous example of a different way of living. When entering the pod, the first thing that strikes you is the huge window a few feet ahead of you, at the ‘far end’ of the pod. Think front loader washing machine. Look to the left and right; everything is there for you to see, but not in plain sight. If philosophically the building was organic then it makes perfect sense that the lacquered pinewood interior design should follow. Every element neatly fixed and fitted, a cupboard whose door converts into a desk or dining table. A place for clothes of sufficient size for a few days clothing. A space for a rolled-up futon. The bathroom is actually a joy, but not useful if you are into swinging cats. It seemed as though the whole thing was made out of one piece of moulded plastic. The futuristic-looking electrical equipment fitted neatly into a small customized unit which would sit happily on the set of any self-respecting retro sci-fi show on Netflix.

Locked in a Battle

But weighing heavily was that the building was falling further into disrepair every year. The facade looked grim and grimy. It’s obvious that it needed a care plan. The tower was locked into a battle, not of its own making, in poor condition with land values soaring it’s at risk.

Whilst a few owners understood that the place must be preserved, others, likely the majority, simply wanted to cash in their chips and get out. That proved to be a complex manoeuvre. It was not so easy because while the value of each unit had increased due to international interest the investment was locked into something with an astonishingly uncertain future. The figures banded about in no way equated to purchasing another flat in the city. Achingly close to the age a building would need to be to be seriously considered for protection, it still remained a few years off. While most conservationists saw the tower of huge significance, the prevailing mood amongst owners was that it should be sold to a developer giving them money to live somewhere most hospitable.

Sadly, the building did not survive; in April 2022, the process of dismantling it began. 23 ‘pods’ were saved with varying degrees of success. The plan is that 14 will be returned to their original operational state (in as much as that is possible), and nine will be returned to shells.

Photo Credits: Howard Morris