Hackney’s German Hospital

The 1936 Modernist wing of the German Hospital in Hackney

A story of the best and the worst of the 20th Century

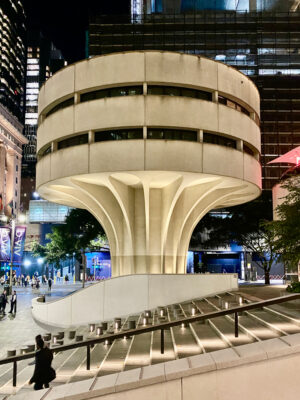

This is a picture of the rooftop terrace for convalescent patients to enjoy fresh air and sunlight. Like the rest of the new 1936 wing of the German Hospital, this terrace embodied the most advanced concepts in hospital environments. Hackney, in east London, had a German Hospital since 1845, serving the tens of thousands of people of German heritage who lived in London and Great Britain, as well as, increasingly, the wider community. Before today’s sophisticated diagnostic tests a patient’s answers to a doctor’s questions were of great importance in disclosing what was wrong. So staff and patients who shared a common, first language was hugely useful quite apart from making patients feeling culturally comfortable. But four years later, in 1940, Britain at war with Nazi Germany had interned the entire German medical staff as enemy aliens on the Isle of Man.

Dr Otto Bernhard Bode was the head of the hospital in the 1930s. He was a member of the Nazi party. The hospital’s staff had close ties to the Hamburger Lutherische church whose pastor was a most enthusiastic Nazi. The story is that during the blackout introduced after the outbreak of war in September 1939, lights were deliberately shown from the hospital as a signal to the Luftwaffe. The hospital’s staff were all replaced and the hospital, now German only in name, continued in operation throughout the hostilities.

Notwithstanding widespread anti-German feeling in the local and wider population during the First World War, the hospital had continued to operate and wounded and ill German prisoners of war were cared for in the hospital.

The new wing was designed by the Scottish practice of Burnet, Tait and Lorne whose work was breathing in the new ideas of Modernism after the retirement of Sir John Burnet. The firm had designed the distinctly modernist looking Royal Masonic Hospital in Ravenscourt Park, London, and was heavily influenced in the design of the new wing of the German Hospital by Alvar Aalto’s tuberculosis sanatorium in Paimio, Finland. In these works we see the emergence of Corbusier’s ideas, ribbon windows and terraces for example.

We’re heavily indebted to Mike Mueller who lives in the building, now called Bruno Court, who was kind enough to show us round and enable us to photograph this hugely pleasing building. The ground-breaking airy and fresh design for patient care and cure serves also to make the flats, high ceilinged and with plentiful light streaming through the large windows, spacious and luxurious. The building is an L-shaped steel frame structure finished in yellow sand-lime brick. Mike points out how the curves, of the sun balconies, the roof terrace, even the gorgeous stair rails, contrast with and soften the “rectangular linearity of the …building.”

The new wing had nurses’ accommodation, a third-floor maternity ward with delivery room in the cantilevered extension at the north end of the building. While the maternity ward, hanging off the building, is striking, its design was driven by the fact that it proved the only way to squeeze the facility onto the small and narrow site, the only land remaining to the German Hospital.

The fourth floor was the children’s ward, with a sun balcony onto which the

beds could be wheeled running the whole length of the western side.

The southern end of the building has cantilevered bed balconies.

Great care was taken to make the new wing as light and airy as possible;

its corridors were lined with primrose-coloured Janus tiles imported from Germany.

In 1948, following its creation, the German Hospital became a General Hospital in the new National Health Service with 217 beds. In 1974 it became a psychiatric and psychogeriatric hospital. But by 1987 its days as a hospital were over and after a period partially empty the hospital was closed and its services transferred to the new Homerton Hospital. The building was left until 1996 becoming increasingly derelict except for being given a Grade II* listing, which saved its exterior.

In 1996 developers converted the building into Bruno Court with 19 apartments. Mike, our guide, bought his flat in 2013. He fell in love with the apartment and the building, telling us how the building is a community and that residents seldom leave. People are surprised to come across Bruno Court, a building that remains striking because of its bold and deceptively simple design, its freshness and clarity. It overlooks on one side, the original hospital buildings and on the eastern side sits Fassett Square, a pleasant garden square of terraced houses which has particular notoriety as it was used for the original design of Albert Square in the BBC’s soap opera East Enders.

Mike says that if he could go back in time he’d like to see the Modernist wing of the German Hospital in the years when, having served its purpose as a hospital, it was in decay. A building needs to be used, ideally to be lived in, by people who get joy from the brilliance of its design. Bruno Court really is such a building.

Our thanks to Mike Mueller.