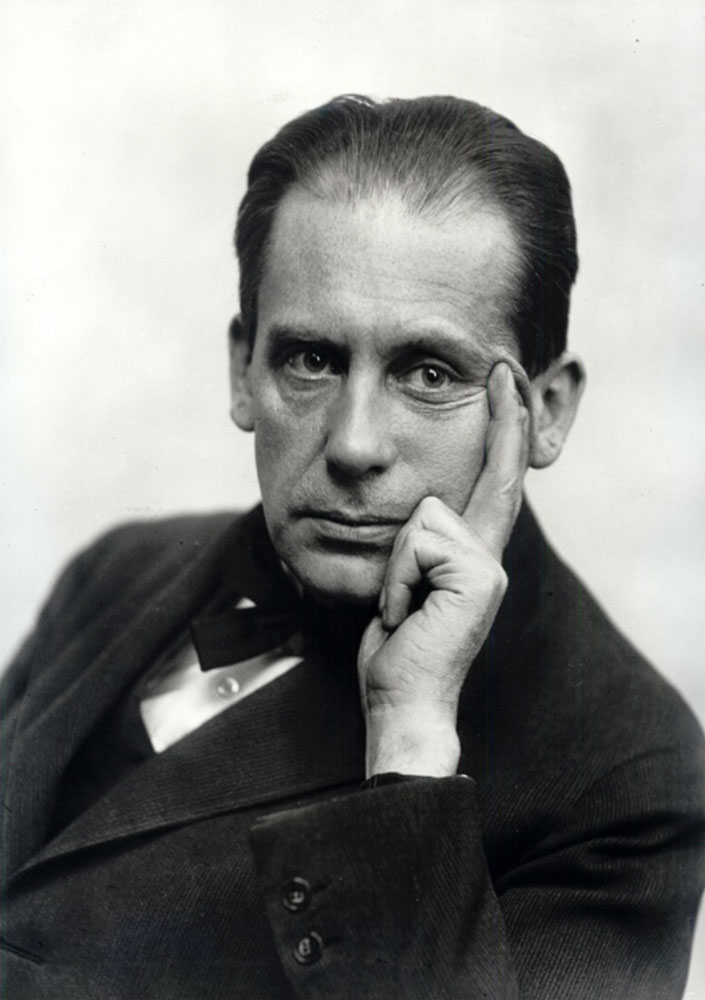

Walter Gropius

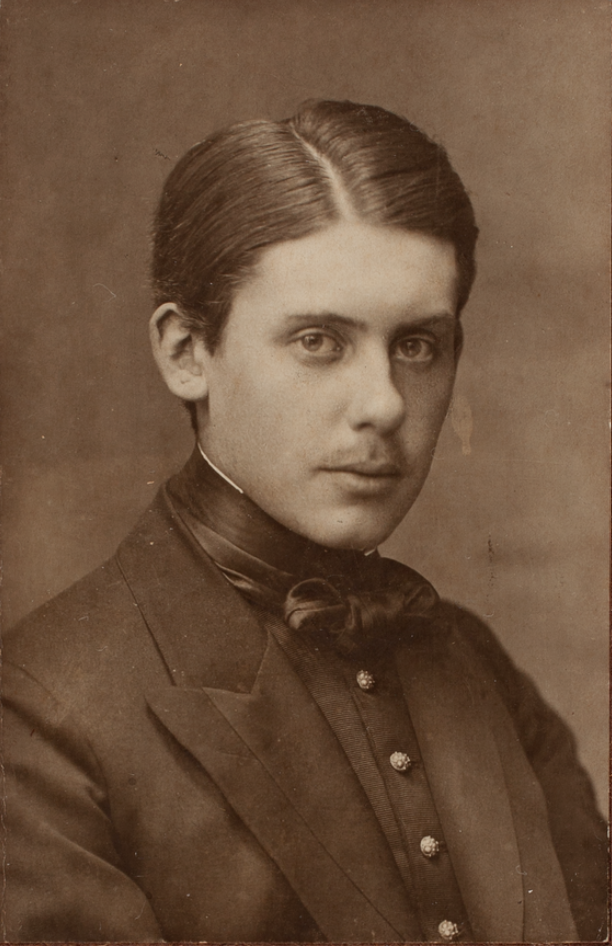

Walter Gropius 1883 -1969, Architect, founder and first Director of the Bauhaus.

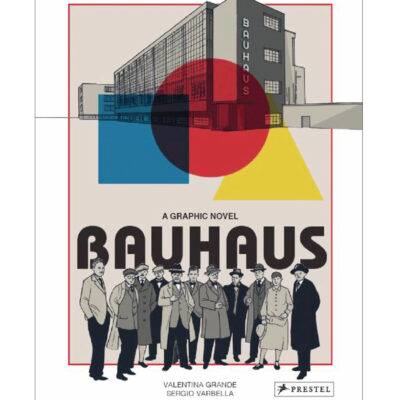

It’s hard to imagine the modern world without recognising Gropius’ enormous impact, a man who brought together under one roof Marcel Breuer with his groundbreaking furniture designs, Annie Albers woven wall hangings, Joost Schmidt’s Bauhaus typography and Oskar Schlemmer’s theatre workshops. Today we take for granted different disciplines merging and feeding into each other, if Walter Gropius had not written his Bauhaus Manifesto and all that followed, perhaps modern design might have gone in a quite different direction potentially crushed under the weight of 20th-century politics.

Walter Gropius, a Berliner born into an upper-class family, he was well travelled and well connected. Married to larger than life Alma Marler, the widow of composer Gustav Marler, they divorced in 1920 a few years after the death of their child Manon. Walter married his second wife and life partner Ise Frank in 1923 after what by all accounts was a love at first sight moment, she was fondly known by friends as Mrs Bauhaus.

Gropius studied architecture in Berlin and Munich and spent what today we’d call a gap-year travelling before joining the highly respected architecture practice of Peter Behrens in 1908 where he rubbed shoulders with Adolf Meyer, Le Corbusier and Ludwig van der Rohe. Two years later, in 1910, he left Behrens’ practice to set up shop with Meyer, initially, Meyer ran the office but very soon they became equal partners. One of their key projects was the design of the Fagus Factory, the Fagus Fabrik in Lower Saxony (1911-1913) considered an important milestone in the development of early Modernism.

Walter Gropius TU Munich 1903 (Image Historic New England Gropius House)

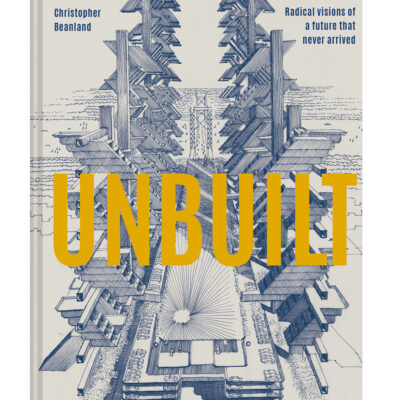

Gropius and Meyer took part in the highly anticipated 1914 Deutscher Werkbund exhibition in Cologne presenting the design for a factory which drew a lot of attention and was recognised as another important moment in Modernism. Then the war came and everything changed, perception, the power of dynastic families, borders, in this atmosphere new ideas emerged.

Gropius returned from the war having served on the Western Front. He became part of a large group of avant-garde artists and architects known as the November Group, Der Novembergruppe, which formed in December 1918. The members had much in common, shared experiences, political views and a yearning to be part of a socialist revolution where the desires of people and art were intertwined. All this happening against the backdrop of the Russian Revolution after which the group was named.

As life normalised in 1919 Walter Gropius accepted the role of head of the Work Council for Art, Arbeitsrat für Kunst (which had been founded by Bruno Taut a year earlier), it was also known as ‘Art Soviet’, a union made up of architects, artists, writers and sculptors. Whilst this was, in reality, pulling away from the November Group, Gropius did in fact work closely together with the group and with the Deutscher Werkebund. These need to be seen in the context of what was happening nationally, it was a time of the great flowering of ideas of all strands of political ideology from both the left and the right, ideas were shared, developed and noted. An architects’ letter writing group emerged, the Glass Chain, Die Gläserne Kette, with Bruno Taut as a key figure, it took the form of a chain letter, today surely they’d be a WhatsApp group:) Gropius’ pen name was Maß.

Walter Gropius harnessed all that creative energy into something tangible. He wrote the Bauhaus Manifesto in 1919, a four-page pamphlet, which was also a roadmap for his vision for a new unified teaching programme that could be delivered in a new school. He imagined a place that would bring together the arts without differentiating between fine and applied arts, where crafts would be taught alongside furniture design, typography, graphic design, ceramics, bookbinding, glasswork and more.

‘Let us, therefore create a new guild of craftsmen without the class-distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsmen and artists! Let us desire, conceive, and create the new building of the future together. It will combine architecture, sculpture, and painting in a single form, and will one day rise towards the heavens from the hands of a million workers as the crystalline symbol of a new and coming faith’.

Bauhaus Manifesto 1919

The Bauhaus was born and Gropius was determined it would become a physical reality and utilised every contact he had both professionally and personally. It was created through the negotiated merger of two schools, the Academy of Fine Arts and the School of Arts and Crafts.

Haus am Horn Bauhaus Weimar for 1923 Bauhaus Werkschau (Image Sailko CC BY SA 3.0)

Underpinning the philosophy was function over form, classes were taught in a new way, Gropius brought in Johannes Itten early on, a charismatic teacher with a strong following in Vienna, to teach the preliminary programme, which all students had to attend, its emphasis was the whole artistic education of a student. Bear in mind that the fluid nature of the curriculum meant that what was taught in the Bauhaus evolved as a reaction to the ideas of the teaching staff, Walter Gropius and later Directors. Architecture was taught from 1927, and pre-1925 women students were pointed towards the weaving classes. Change saw the letting go of some of the early ideas which were not so much in evidence by the time the school closed in 1933.

Staatliches Bauhaus opened in the town of Weimar in Thuringia on the 1st April 1919 with Walter Gropius as its Director, in its first term it had attracted 200 students from Germany and beyond, the teaching staff reflected the international feel of the place though outside of Germany most students came from Austria, Switzerland and Hungary, all completed a craft apprenticeship.

To return to Swiss painter Johannes Itten for a moment, Itten was by any definition brilliant and eccentric, he encouraged the students, all of whom came into contact with him as he taught the preliminary course, to deep dive into themselves, coupled with his fascination with mysticism, vegetarianism, and his encouraging his devotees to also dress in cassock like robes, sporting striking unconventional haircuts meant that the school quickly gained a reputation as being rather eccentric. In fact, with Gropius’ full buy-in the Bauhaus was a hothouse of true creativity and students were given freedom to express themselves in a way not previously seen, studies ranged from pure craft, fine and applied arts through to theatre studies added in 1921

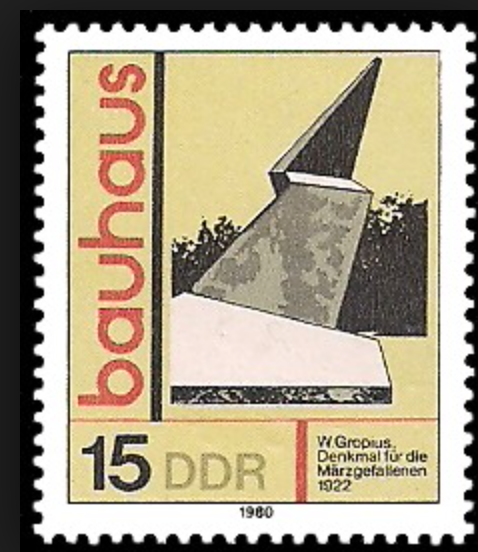

Monument to the March Dead by Walter Gropius honouring the workers who lost their lives during the Kapp Putsch

During this period Gropius maintained his own architectural practice, often employing Bauhaus students on projects including a concrete lightening strike as a Memorial for the Victims of the Kapp Putsch in Weimar (later destroyed by the Nazi Party).

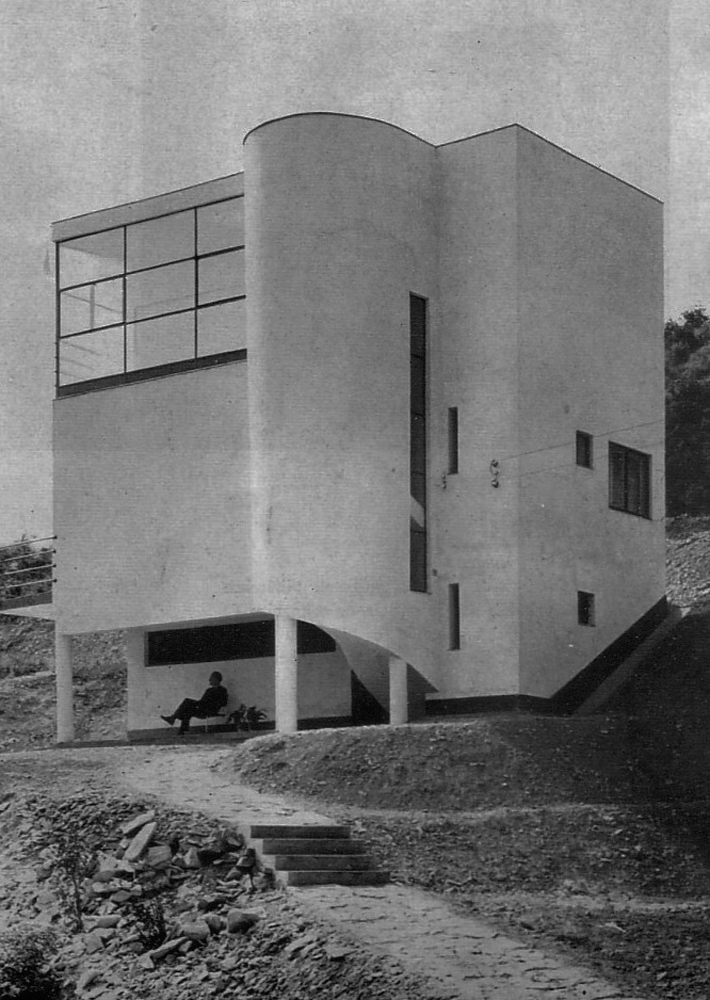

Whilst the hotbed of creativity remained central to the Bauhaus ethos, in 1923 Walter Gropius realised that he needed to steer the school on a different course, focussing its interests and aims more towards the increasingly industrialising Europe, towards ‘Art and Technology: A new unity’, which led to Itten leaving the Bauhaus and his replacement by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Now Gropius’ Bauhaus showcased its creativity and expertise to the outside world, taking part in local and international exhibitions and trade fairs and the highly anticipated Bauhaus Exhibition in Weimar during ‘Bauhaus Week’ in the summer of 1923. Gropius built the Haus Am Horn, especially for the exhibition. It was designed by the school’s youngest Master, Georg Muche who was supervised by Adolf Meyer with interior designs supplied by Bauhaus students. Gropius’ intention was that this would be the first of a series of buildings, a sort of educational settlement.

Masters and teachers including Paul Klee, Lionel Feininger and Vasilly Kandinsky joined the faculty and Marcel Breuer a former pupil joined Gropius as a teacher. But nothing can ever remain in its own bubble and Gropius saw this, his school was coming under artistic pressure from hard-right wingers and this took on a financial aspect when the Thuringian State Government withdrew funding for the school. The students did all they could to help and signalling the level of respect afforded to Walter Gropius, a Friends of the Bauhaus circle was created whose members include Albert Einstein and Marc Chagall, but this was not ever going to be something that could be sustained longterm.

Gropius understood the school was in a precarious position, he was put under pressure by local politicians to resign in 1925 and quickly realised that the school had to move out of State. Some of the staff decided to remain in Weimar creating the Weimar State Architectural College, the Staatliche Bauhochschule, under the leadership of Otto Bartning who himself resigned when the Nazi party came into power in Thuringia. Today the school is part of the Bauhaus University Weimar

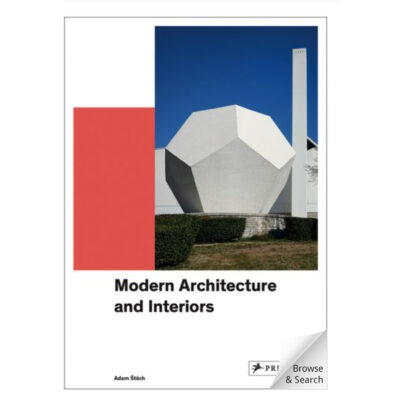

Dessau was chosen by Gropius as the spot and the Bauhaus was welcomed. Gropius built the new school, with which we are so familiar today, as well as designing the Masters’ houses for the teaching staff in 1926.

Walter Gropius, Composer Bela Bartok and Artist Paul Klee on the Terrace of Gropius’ House in Dessau 1927 Image Historic New England

Masters House, Dessau Image Howard Morris

Walter Gropius handed over the directorship to Swiss architect and committed communist Hannes Meyer in 1928 and left the Bauhaus. He returned to Berlin, in a country that was shifting to the right. It became increasingly clear that National Socialism and Gropius’ modernism were not compatible and should the Nazis come to power, artistic endeavour would come under extreme pressure. After 1933 when Hitler became Chancellor, Gropius’ architectural practice entered the competition to build the new Reichstag, however, it was quickly crystal clear that the new regime would not tolerate or understand anything that mattered or acted as a driver for Gropius (let’s not forget that under racial laws had his daughter, Manon, by Alma Mahler, survived she would have had enormous problems as would have Alma). Gropius’ connections with the Modernist movement and Nazis hatred of this architectural form meant his career was in very real jeopardy and any attempts to designs built were going to be blocked by petty officialdom.

The Electricity Showroom, London Gropius & Maxwell Fry ©

In 1934 pretending to go on holiday to Italy, he instead made his way to England with his wife and daughter Ati helped by Edwin Maxwell Fry. This created a real moment when it was hoped that the Bauhaus could be set up in England. Gropius went into partnership with Maxwell Fry, together they built several projects during what was to ultimately be a brief period in London. These included the Electricity Showrooms at 115 Cannon Street, in the heart of the City, Impington College School in Cambridgeshire and some private homes including the home of British actress Constance Cummings and playwright and MP Ben Levy at 66 Old Church Street in Chelsea London.

Gropius also worked together with Marcel Breuer and Laszlo Moholy Nagi (both of whom had also fled to England) for Jack Prichard’s Isoken company in Lawn Road, Hampstead. The new book Isokon and the Bauhaus in Britain by Magnus Englund and Leyla Daybelge about the Isokon is an excellent read on the topic. In reality, Gropius’ career stuttered in England and in 1937 he accepted an offer to move to the United States and become a Professor of Architecture at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, by 1938 he was elevated to Chair of the Department.

Marcel Breuer followed Walter Gropius to the US where successful professional collaborations which had begun in Germany continued. Together they designed the Pennsylvania Pavillion for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Here were too distinctly European men informing Americans about one of the founding states in the Union! They even lived next door each other. Gropius had been given a plot of land funded by philanthropist Helen Storrow, Breuer was given the plot next door, each helped design and build the other’s home, both the Gropius House and Breuer House were completed by 1938. The homes were not only splendid examples of modern houses but were also utilised to show students how modernist design could be interpreted in the United States, perhaps there was also a nod to the Master’s Houses in Dessau that they both left behind. They were commissioned by a family to build a third house in Pittsburgh, the 1940 Frank House, Breuer more or less designed all the furniture and Bauhaus weaver Anni Albers, who was by now at Black Mountain College, was asked to create wall hangings.

Gropius House (Image Historical New England)

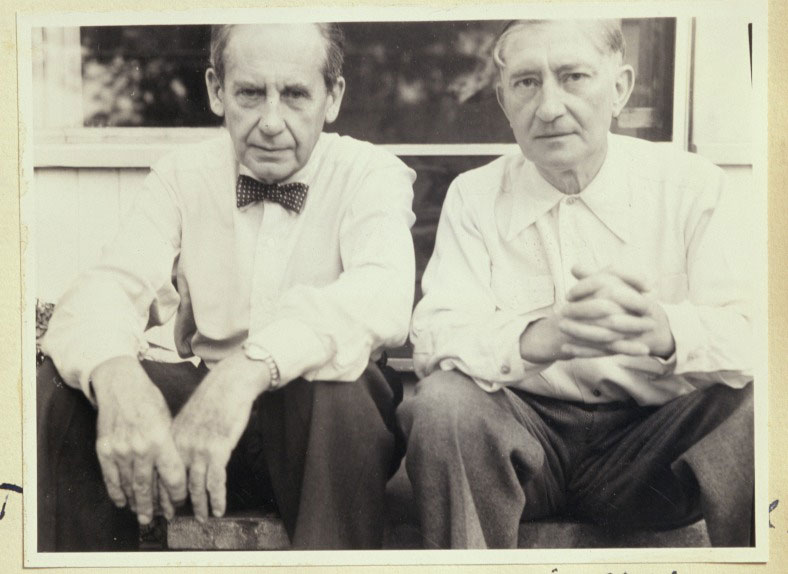

Walter Gropius and Josef Albers 1946 (Image Historic New England)

At the end of the war in 1945, Gropius became the eighth founding member of TAC, The Architects Collaborative, joining John and Sarah Harkness, Robert and Louis McMillen, Benjamin Thompson and Norman and Jean Fletcher in Cambridge Massachusetts, it was a hugely successful practice.

Walter Gropius, who said “The ultimate goal of all art is the building” worked as part of TAC until his death in 1969 in Boston.

Walter Gropius at CIAM 1951 seated next to Le Corbusier (Image Historic New England Gropius House)

Clark Art Institute Williamtown MA built by TAC

Need to know before you go:

Gropius House is maintained by Historic New England and is open to visitors Wednesday – Sunday from May to October and Saturday -Sunday from November to April. Last Tour 4 pm. The house is set in five and a half acres and has lots of lovely spots for picnics. For more details about the Gropius House including how to get there, please check the website vis this link: Historic New England