Bruno Taut

The German Architect Who Said

‘Colour is the Joy of Life’

Bruno Taut was a German architect, theorist, painter, pioneer of colour in modern architecture, urban planner and early fan of the Garden City Movement. And I haven’t even got on to his pacifism and desire for social justice. His contemporaries are now names that trip off the tongue such as Mendelsohn, Mies Van Der Rohe, Gropius and Sharoun.

Born in Konigsberg, now Kaliningrad in 1880, Taut was educated at the Baugewerkeschule trade school. His career began in Berlin in 1903 working for Bruno Möhring an important art nouveau (Jugendstil) architect. He moved to Stuttgart in 1904 to work for Theodore Fischer who had a special interest in public housing. It was here that Taut studied urban planning. In 1909 Bruno Taut returned to Berlin to form an architecture practice with his brother Max and Franz Hoffman.

Falkenberg Garden City ‘the paintbox settlement’ Image Mangan 2000 CC BY SA-3.0

The intriguing thing about Taut is to think about how much he was an early contributor to the way we think about colour in our homes, inside and out. Taut didn’t merely theorise he lived his views in his own home.

Memorial plaque Gartenstadtweg 53 Falkenberg Gartenstadt Image OTFW CC BY SA-3.0

Barbara Klinkhammer of the Bauhaus Universitat Weimar in The Spacial Use of Colour in Early Modernism captures Taut’s vibe in one of his early homes and gives us all a colour coding system that can’t fail;

Colour in Early Modernism

‘The colours he uses for the interior of his house built 1926-27 in Berlin-Dahlewitz follow precisely arranged relations. Accordingly, the bright red applied to the ceiling of the living room, positioned in shade during daylight. is carefully balanced against the green of the surrounding grass in the garden.

Ultra-marine in the adjoining room contrasts with the chrome-yellow of its facing wall. Bright colours were never exposed to the direct sunlight but were applied in the shaded areas or side-light. Accordingly, the direct sunlight hits most of the time blue or a deep, dark red’

Residential Block in the Falkenberg Garden City, Bohnsdorf Berlin Image Bergfels CC BY 2.0

Taut’s Falkenberg Gartenstadt (garden city) in Berlin was fondly described by locals as ‘tuschkastensiedlungwhich’ the paintbox settlement, referring to its use of colour. Built between 1913-15 it received wide acclaim. The Institute of Urban Dreaming has an excellent article about a recent visit.

Image Mangan 2002 ‘Tuschkastensiedlung’ Falkenberg Garden City CC BY SA-3.0

Taut and Hoffman Partnership

The Taut and Hoffman Partnership had tremendous energy. They caught the public’s imagination with their Iron Eisensmonument presented at the 1913 Leipzig Construction Fair. One year later the famed Glass Pavilion was created for the Cologne Deutscher Werkbund Exhibition. Whilst the pavilion has not survived, one black and white photo remains. Author Paul Sheerbart wrote a book in Taut’s honour called Glasarchitektur declaring the beautiful prismatic glass-domed pavilion ‘architecture in glass’.

Bruno Taut’s Glass Pavilion For The Cologne Werkbund 1914 Exhibition

After WWI at the time of the November Revolution, Taut became a founding member of a collective of Berlin-based artists, architects, sculptors and writers called the Work Council for Art, the ‘Arbeitstrat für Kunst’, He was joined by Caesar Klein, Adolph Behne and in 1919 Walter Gropius. The signatories of its First Manifesto are a stary list that shaped the future of design and architecture.

Die Glaserne Keitte,

Bruno Taut was also the initiator of the famed November 1919 Glass Chain, Die Glaserne Keitte, a chain of letters that were sent from one architect to the next and is considered to be the basis of German expressionist architecture.

Hufeisensiedlung Estate Berlin-Britz:Award winning interior of Tautes Heim restored by Katrin Lesser & Ben Buschfeld www.tautshome.com CC BY 3.0

Hufeisensiedlung

By 1921 Bruno Taut had become Magdeburg’s city architect a role he managed from his Berlin office. He remained in the post for three years, his role to create and implement the municipal planning programme of the city, of special note is the Garden City Colony. He returned to Berlin to become the Chief Architect of the GEHAG design office.

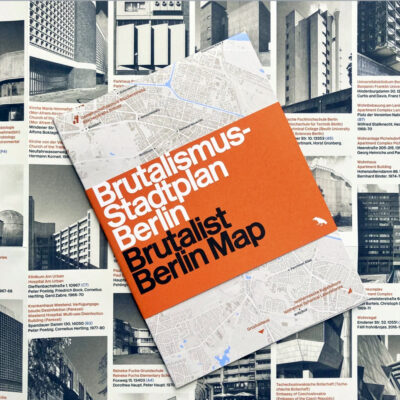

Taut’s task was the urban planning of large housing estates for a city that was expanding at a breakneck speed. Some of Taut’s most memorable work is from this period, such as the ‘Hufeisensiedlung’ Horseshoe Estate in the Britz neighbourhood of Berlin and the Onkel Toms Hutte colour flooded housing estate, and the laying out of Wohnstadt and Schillerpark.

Berlin ‘Hufeisensiedlung’ Horseshoe Estate © A.Savin, Wikimedia Commons

According to Sean Kisby in Bruno Taut Architecture and Colour

‘A journalist, writing in 1930, described one of Taut’s suburban estates as “exemplary, of a most simple modernity… Each street has a face and its colour behind the veil of pine trees. That one over there has been given various nuances of yellow, whilst this one here displays but a single pink; one can see some in a wistful sky blue and others whose fine, warm, red tone has an almost Bordeaux-like quality’

Werkbund Exhibition

Amongst Taut’s numerous developments of note was his 1927 design for a detached house for the Werkbund Exhibition in Stuttgart. House number 19 stood bathed in colours in contrast to its neighbours.

Taut became a Professor whilst continuing with his burgeoning architectural practice, he taught at the Technical University of Berlin and joined both the Deutscher Werkbund and the Berlin Zehner Ring during this prolific period. He was invited to become a member of the Prussian Acadamy of Arts and made an honorary member of the AIA.

Kulturbolschewismus

The rise of National Socialism brought with it very difficult times for Taut, he was considered a ‘kulturbolschewismus’, a cultural Bolshevist. He had been a prominent communist activist for the whole interwar period and this put him under the nazi’s spotlight.

He decided, as a first step, to visit the Soviet Union in 1932 in response to being offered the opportunity to build a large housing complex in Moscow, whilst this had not been his first visit having previously visited in 1923, and despite his fascination with developments in Soviet architecture, (an unfinished 1929 manuscript ‘Russian’s Architectural Situation’ attests to this) it was quickly clear to him that the Moscow he dreamed of and the reality on the ground of living in the Soviet Union were two different matters. Perhaps he had arrived in the wrong decade, the climate was changing for architects not willing to reject functionalism and embrace social realism. A longterm stay in Moscow was now not feasible.

Taut briefly returned to Berlin but had to resort to hiding out in a friend’s apartment, its hard to imagine how shocking that must have been for a man who less than five years earlier was trusted to deliver large scale housing projects, now his life depended on having friends able to tip him off that he was on a list to be arrested.

Professorship cancelled

His world turned upside down, his Professorship cancelled, removed from the list of members of the Prussian Acadamy of Arts, he quickly left first for Switzerland. Helped by the International Architects Association who recognised the need to act fast, they invited him to deliver a world lecture tour beginning in Japan. There is a suggestion that he had hoped to get to the US and remain there but this did not materialise, Taut found himself living in Japan for three years, it was clear was that it was not safe for him to return to Germany in the foreseeable future.

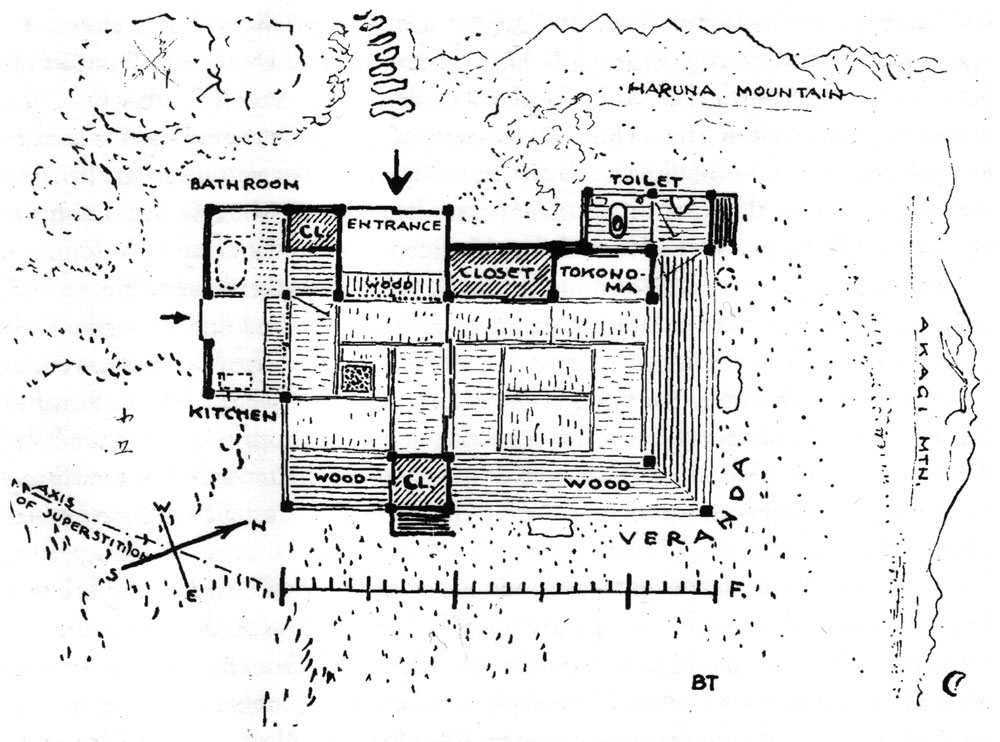

Shenshintai Takasaki Japanese Temple Image in Public Domain

His creativity did not diminish in Japan however whilst he wrote and designed, his architectural career did not take off. He left Japan to live in Turkey in 1936 joining a friend and former Berlin city planner Martin Wagner who had also left due to the political climate in Germany.

University of Ankara, Turkey Image: Avniyazici CC BY SA-3.0

Bruno Taut’s was awarded a commission to design the University of Ankara and a series of other lesser projects. One which was widely known in Turkey was the funeral bier for Kemal Ataturk. Sadly he died two years later in 1938 whilst living in Turkey.

Had he survived the war, one can’t help but imagine the mark he would have made on the rebuilding of post-war Germany or if he had chosen to live in America how his career would have continued to develop had it not been so cruelly cut short.