Richard Neutra

Think Neutra; immediately, his homes and immense contribution to Californian Modernism come to mind. But there is so much more to consider: a man who drew inspiration from pre-war Hapsburg Vienna to create an architectural vocabulary for the Hollywood elite and baby-boomer Southern California.

Richard Neutra was born in Leopoldstadt, Vienna, Austria on the 8th April 1908 to an educated, comfortably off, Jewish family, attending the Sophiengymnasium in Vienna and later the Vienna University of Technology, the Technische Universität Wien, where his teachers included Karl Mayreder and Max Fabiani. He studied under Adolphe Loos and was a huge fan of and highly influenced by Otto Wagner.

Vienna had a profound influence on the young Neutra. It was the capital of the vast, polyglot Austro-Hungarian Empire, which stretched across Central and Eastern Europe, home to Klimpt, Schiele, Moser, Musil, Broch, Schoenberg and Mahler and the father of psychoanalysis, Freud.

Biorealism

‘Biorealism was no mere aesthetic approach; it applied the biological and psychological sciences to foster solutions for the built environment. Influences from Neutra’s formative years led him to believe that biorealistic design was the only way the human race would survive. He spent his life and career devoted to this single cause’.

When the First World War broke out, Richard Neutra served in the reserves of the Imperial Austrian Army as a lieutenant of artillery in the Balkans, briefly taking time off to go to Germany to complete his final architecture exams. That crisscrossing in and out of countries became a familiar pattern for him – he was on the move, and so were the borders.

His first job post-war was in Zurich, working with respected Modernist landscape architect Gustav Ammann, then back to Germany in the Spring of 1921, at a time when the Weimar Republic was going through enormous change. From March to September, Richard Neutra was employed in the municipal construction office in Luckenwalde, Germany, under Josef Bischof, the city’s architect. They planned a striking multi-denominational cemetery in the middle of a forested area. This was a natural next step for Neutra as a way of experimenting with what he had learned with Ammann. Neutra did not stay to complete the project. In recently uncovered documents, his vision for the funeral home and on-site housing for the employees showed the huge promise he would realise later. Neutra’s design differed from that which was later completed by his replacement.

Joining Erich Mendelsohn

A role in the Berlin office of Erich Mendelsohn’s architectural practice was not to be turned down. Until his dramatic departure from Germany in 1933, Mendelsohn’s firm was considered among Germany’s most successful modernist practices. Neutra assisted Mendelsohn with the urban planning project for Haifa, the Berliner Tageblatt Building and the 1923 Zehlendorf Housing Estate. Arguably, Neutra could have continued in this role, but he still felt unfulfilled, and the only resolution was to head to America and experience life in the US. He certainly wasn’t entering unchartered waters – Adolphe Loos, who, although not able to establish himself in America successfully, was entirely enamoured and seemingly passed on the bug.

Leaving Berlin with his wife and son, Neutra headed to New York and then to Chicago in 1924, where a chance meeting led him to work in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin East Studio in Spring Green for three months.

Rudolf Shindler

It was immediately clear to Neutra that this is the country he should be in. His old school pal Rudolf Shindler and his wife were living in West Hollywood, and Neutra headed west in 1925 with his family. They moved in with the Schindlers in their Kings Road home. What you could say predictably became quickly clear was that the families’ lifestyles were incompatible. Schindler’s home was at the epicentre of LA bohemian cool, and the Neutras would have seemed rather old-world and buttoned up in comparison. Suddenly, they were all thrown together in a very small space.

The pair tried to make this work as best they could, forming a partnership and entering competitions. Their design for the League of Nations in Geneva was never built; however, it was chosen for a European travelling exhibition. In 1927, they formed a new partnership, adding in urban planner Carol Aronvichi, called the Architectural Group for Industry and Commerce (AGIC). The three men found little success, the partnership short-lived with Neutra and Schindler’s friendship a further casualty. Whether it was artistic differences or simply that Neutra was wholly focused on his career and family to the exclusion of much else, the relationship between the two families and the two designers faltered. First as friends, as architectural practice partners and then, post-split, in competition with each other, Neutra and Schindler lived in the same space for five years from 1925-1930, five, by all accounts, very lively years.

Trying every avenue to earn a living, in 1928, Neutra turned his hand to tutoring at the Acadamy of Modern Art in Los Angeles, where he counted Gregory Ainas as one of his pupils. 1929 was a turning point when Richard and his family became American Citizens, looking back over their shoulders to a Europe leaning increasingly towards extremist politics. While they may not have realised it then, the decision will likely have saved their lives.

Lovell House, Los Feliz

The 1929 commission to build Lovell Health House gave Neutra the opportunity to showcase his first-hand knowledge of Modernism. This was the work that is frequently credited as the introduction to America of International Style.

Lovell Health House images Michael Locke

CIAM Representative

Neutra was invited to become the US Representative to the newly formed Congrès Internationaux d’architecture moderne but was too busy to attend its inaugural meeting in Switzerland. He did attend meetings in Brussels and remained as the American rep until meetings ceased in 1941). Until the Second World War, CIAM was always considered a European project. However, the 1933 fourth congress, which took place in Athens, was a watershed moment. Everything was changing rapidly around the modernists – key members were no longer living in their place of birth. This is credited as the meeting where Corbusier cemented his importance. A very European Neutra sat at the table, representing America. At moments like this, it became clear how clever a choice it was to have Neutra in the role. He had a deep understanding of European architecture, and he was familiar with key characters yet at the same time very connected to American architecture.

That very European part of his sensibilities never left him; he combined his visit to CIAM 3 in Brussels in 1930 with a whistle-stop lecture tour of several European cities and became a visiting teacher at the Bauhaus in Dessau. The decision was where to be – his American career had begun to take off, but that is not to say it was not peppered with real difficulty in the early years. The West Coast was where he wanted to be. However, there were times in the early 1930s when he had a hard time thinking about relocating to the East Coast. The economic impact of the Great Depression was deeply felt across the whole nation, and home-building all but came to a halt. He survived and arguably ultimately thrived in the lean years by working in the film industry at Universal for German emigre Carl Laemmle. The 1932 commission he received to build a mixed-use office building for the studio on the intersection of Hollywood and Vine, comprising a ground-floor restaurant and shops with offices for the studio above came at absolutely the right moment. Politically aware, Neutra did dabble with other ideas, and it should be noted that he had expressed an interest in housing in the Soviet Union in the early 1930s, though this did not lead to him accepting a commission which would have come back to haunt him.

The invitation to be included in Philip Johnson’s major 1932 show about Modernism at MoMA in New York, Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, again increased his prominence and again served as a painful reminder of the split with Schindler, who was not invited. From this point his career went from strength to strength, at each turn along the way he was invited to join prestigious organisations whilst receiving a huge number of commissions to build family homes. Regardless of the increasing fame with each commission, he did not lose his fascination with how people live in a house. The notion of a client answering a detailed questionnaire before Neutra began designing for them seems entirely obvious now, but it was not when Richard Neutra presented this idea to clients.

In 1936 he employed Julius Shulman as a draftsman and to take photos of the Kun Residence. This launched an important architectural photography career for Shulman and a long collaboration followed with Neutra.

From 1942 to 1946, Richard Neutra sat on the advisory panel of the Architectural Review and was also one of a group of architects who built the Case Study Houses from 1945-64. His winter home for Edgar J Kaufmann in Palm Springs was an immediate international hit.

Kaufmann Desert Home 1946 Image Pmeulbroek CC BY SA 4.0

Featuring on the cover of Time Magazine was and remains a marker of success and in 1949 it was his moment – described as ‘one of the best and most influential moderns’. By now he was in a partnership with Robert E. Alexander which lasted until 1958, working on large-scale commercial designs and many notable homes. To have a Richard Neutra home mattered in Southern Californian society.

Sometimes, the entirely unexpected happens, according to an interview with Raymond Neutra (Richard’s son). In 1953, Richard had a heart attack and was hospitalised in East Hollywood. He recalled; ‘By pure coincidence, he was placed in the same room with Schindler, who was undergoing treatment for prostate cancer and had just a few months to live. The two men hadn’t spoken for many years before reconnecting there’. Old emotional wounds were healed over the few days there were rooming together remembering old world Vienna.

In 1965, Neutra went into partnership with his son Dion. It was a prolific time for Neutra and he built a series of villas in Europe. Amongst these was a commission by the politician and publisher of Die Zeit, Gerd Bucerius for a family home. That same year, Neutra accepted the role of Consultant to the Austrian Government for the Building Research Organisation.

Richard Neutra died in Wuppertal, Germany on April 16, 1970.

A selection of Richard Neutra projects:

1929 Lovell House Los Angeles California, credited as the US’ first International Style home aka Health House

1932 Neutra VDL Studio and Residence aka the Neutra Research House aka the Van der Leeuw House

1934 Sten Frenke California (for Russian actress Anna Sten who was signed to Universal)

1934 Beard House Altadena California

1935 House for Josef Von Sternberg, San Fernando Valley (Director of The Blue Angel) House demolished 1972

1936 Josef Kun House

1937 Koblick House, Silver Lake

1938 Windshield House, Fishers Island New York State. The subject of a film by the granddaughter of the owner’s Windshield: A Vanished Vision. The house collapsed shortly after completion in a hurricane was rebuilt then collapsed again in another hurricane in 1972

1937 House for Leon Barsha (numerous films and The Twilight Zone and Rawhide for Television)

1937 Miller House Palm Springs California designed for actress Grace Lewis Miller

1937 Strathmore Apartments in Westwood, residents included Orson Wells, Luise Rainer and Dolores Del Rio

1938 House for Albert Lewin, Hollywood Film Director (The Picture of Dorian Grey) later home to Mae West

1937 Landfair Appartments Westwood LA, International Style

1940 Davey House, Carmel

1941 The Bonnet House

1947 Kaufmann Desert House, Palm Springs Califonia built as a holiday home for Edgar J Kaufmann retail magnet, considered an excellent example of Biorealism

1947 Tremaine House Montecito California

1948 – 1961 The ‘Neutra Colony’

Sokol House 1948

Sokol House Richard Neutra 1948 Image: Michael Locke

- Edward J Flavin House 1957

Edward Flavin House Richard Neutra 1957: Image Michael Locke

1949 Millard Kaufman House Hollywood Hills for the screenwriter who created Mr Magoo

1950 Holiday House Motel Malibu California

1955 Perkins House, Pasadena for Constance Perkins with noted indoor/outdoor pool

1955 US Embassy in Karachi.

1956 Chuey House

1957 Airman Memorial Chapel at the Miramar Naval Air Station, San Diego California

1959 Oyler House Lone Pine California, famed small scale commission for a ‘working class government employee’

1960 The Sale Residence

1962 Eagle Rock Clubhouse LA (rumour has it that William Holden was on the guest list for the official openning)

1962 Los Angeles County Hall of Records with architect Robert Alexander

1962 The Cyclorama Building, Gettysburg battlefield visitors centre, Pennsylvania demolished 2013

1962 Maslon House Rancho Mirage Califonia demolished 2013

1964 The Rice House, Lock Island, James River, Richmond, Virginia International Style

1968 Orange County Courthouse / Central Justice Center

Awards and Honours:

City of Vienna Architecture Prize 1958

Wilhelm Exner Medal 1959 (Austrian Association of Crafts)

Order of Merit Federal Republic of Germany 1959

The Klimt Award, Vienna 1961

AIA Award Southern California Chapter 1939 1947 1949 1963

AIA Fellow 1947

Noted in the Hall of Fame of the 1939 World Fair in NYC

Richard Neutra Room established at the Library of the University of California, LA 1953,

Bicentennial Silver Medal from Columbia University 1954

The Honorary Doctorate University of Graz, Technical University of Berlin, University of Rome,

Honourary Member Union of Hungarian Architects 1963

Benjamin Franklin Fellow Royal Society of Arts London 1965

Cross of the Federal Republic of Germany 1967

Gold Ring, City of Vienna 1968

Honorary President Bund Deutscher Architekten Germany 1969

Posthumously awarded the AIA Gold Medal 1977

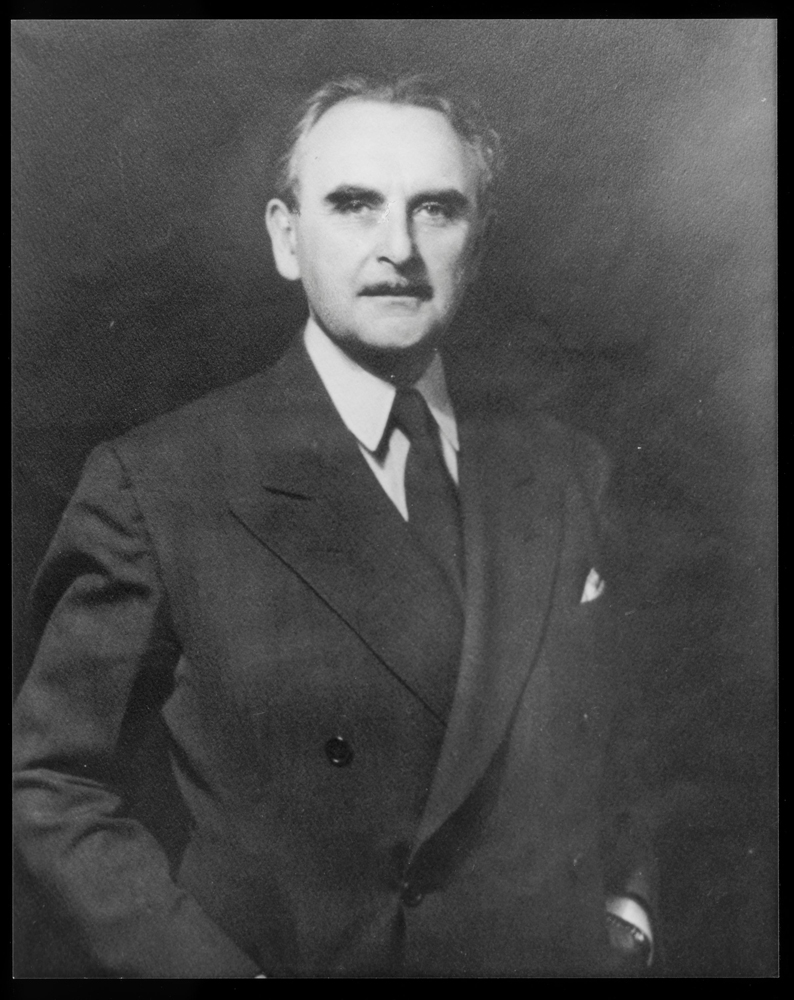

Header image of Richard Joseph Neutra © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10) Julius Shulman photography archive, 1936-1997. Series II. Architects, 1936-1997

Featured image CC BY SA 4.0

Citations:

Reminiscence in a hospital room, published in Archdaily

Bauhaus teaching and lecture tour Matthias Brunner

Richard Neutra’s Ambiguous Relationship to Luxury