Ernö Goldfinger

It seems almost too easy to think about Ernö Goldfinger and simply reel off his ‘greats’, Balfron, Trellick and Willow Road but that would be ignoring the varied and amazing career of a man who transcended one world to become fully entrenched in another.

Architect, Furniture and Toy Designer

Ernö Goldfinger, architect, furniture and toy designer (yes, toy designer) was born into a wealthy, Jewish family in Budapest. The family business involved lumber which led to Ernö spending his early years deep in the heart of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Szaszregen, Transylvania in the Carpathian Mountains and in the Austrian Alps. When he was ten, Ernö was brought back to Budapest to be educated and later continued his studies in Vienna. By the time he’d finished school, the Empire had collapsed, the family had moved to Vienna, there was an assumption he would study engineering and remain close to home.

Paris

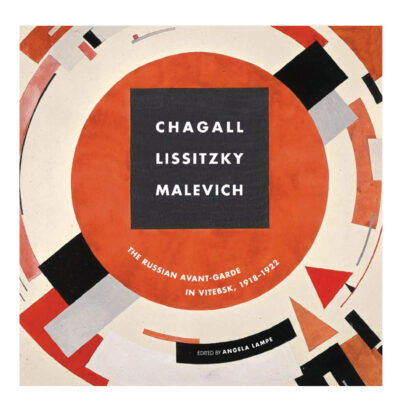

Instead, he headed to Paris in 1920 to study at the École des Beaux-Arts. He hung out with the best, Man Ray, Lee Miller, Max Ernst and more, visiting every important exhibition, including the 1925 Exposition. Goldfinger entered design competitions, ingested the Parisienne cultural vibe and revelled in the best of the city during les années folles; it was here that his political views became fully formed or perhaps another way of thinking of it, Paris was the place where he publicly defined himself as communist, at least in name. Something of a stumbling block for the impatient, headstrong and pretty blunt student Ernö was the daily grind at L’École. It was far too conventional and frustrating for the new breed of post-WW1 students who wanted a different experience…. perhaps they were hearing what their cousins in Dessau were getting up to. Ernö and his fellow students formed a ‘commune’ within the school. Goldfinger’s commune contacted Corbusier (whom Goldfinger hugely admired), and this led to the group choosing Auguste Perret as their Maître. The relationship went further when Perret opened his studio and offered the students, including Goldfinger, a different design experience. In English Heritage Preserving Post-War Heritage, Perret is credited with giving Goldfinger a ‘mastery of concrete’.

Fellow student Andre Szivessy (aka Andre Sive) went into business with Goldfinger in 1924. Their company specialised in furniture and interior designs; the collaboration ended in 1929; Goldfinger wanted to fly solo and opened his own office focussing on interior designs. Architecture did not figure in this new project because, quite simply, he was not offered commissions. Sive was certainly not left behind and went on to a highly rewarding career, and he was later a jury member for the planning of the new capital city, Brasilia.

MARS group

Ernö had met Crosse & Blackwell heiress Ursula Blackwell in 1931. She was a far from an impoverished student of art in Paris, super smart and well connected. They married two years later and had their son Peter in Paris. Fatherhood brought out an expected stream of consciousness in the ever-curious Goldfinger, he began to correspond from Paris with London based, Paul and Mary Abbatt, members of the MARS group (founded by FRS Yorke and Maxwell Fry). The Abbatts dedicated their lives to understanding the role toys play in a child’s development, for both able-bodied children and those with physical or learning difficulties. This thinking, which we take for granted now, was very ahead of its time. The Abbatts travelled widely in Europe and into the Soviet Union, meeting many modern educators and creative thinkers (a number of whom would, in a few short years, become victims of racism). Their approach and desire to visit Russia would have chimed well with Ursula and Ernö. Goldfinger found the Abbatts fascinating and began designing toys embracing their principles. The knowledge the Abbatts gained was translated back home into an educational toy-designing business.

Beyond Paris

Perhaps Goldfinger’s career and life may have developed differently (with all the potential for tragedy); however, politics forced a decision; he was not a French national; he needed to make a very real choice, whether to leave Paris behind and come to England in the wake of the rise of fascism or take his chances. Ursula had already returned home with baby Peter. This would not be an unusual step for Goldfinger, he’d be joining a stellar list of emigré designers who had fled to England bringing with them their knowledge and passion for the Modernist movement. In the end, the Abbatts encouraged Ernö to move in 1934 to London to join Ursula and Peter. As it happens, he had dipped his toe into working in England in 1927 when he accepted a commission to redesign a shop for the American high priestess of beauty, Helena Rubinstein. She hated the design and they got into a legal tangle about fees.

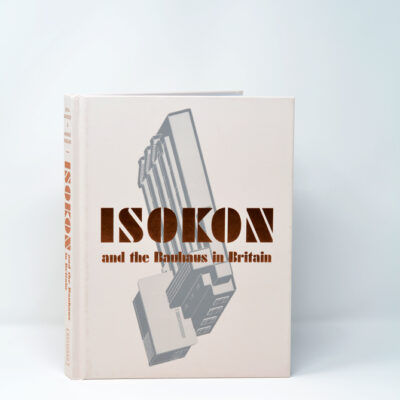

Isokon Lawn Road Flats

Lawn Road Flats

Settled in England, the Goldfingers’ became part of the Lawn Road Flats circle of Molly and Jack Prichard, although they chose not to live in the apartment block, instead close by at Highpoint I in Highgate, which had been built by fellow emigrée, Lubetkin, whom Ernö had known in Paris. Ernö was invited to become a member of the MARS group and later became the ‘Honorary Editor’ of their bulletins.

Paul and Marjorie Abbatts’ pivotal role

The design team became more and more important figures in Ernö’s life; according to the Architectural Review, ‘Goldfinger was soon designing toys, logos, exhibitions and catalogues for the Abbatts, as well as adapting their workshop in Midford Place, off Tottenham Court Road, London, with FRS Yorke as ‘local architect.’ The structure at that time for emigree architects was that they needed to work with an architect who was both British-based and accredited – MARS co-founder Yorke fulfilled that role for Goldfinger on this project.

Goldfinger and Mary Medd (née Crowley) were commissioned in 1934 to design an experimental nursery in the Abbatts home for the Contemporary Industrial Design Exhibition. Until then, a nursery in a British home would have had a distinctly Victorian feel. Bearing in mind that for Mary and Paul their home was completely entwined in a passion they now shared with Goldfinger and that their flat also doubled as the HQ for the Nursery Schools Association, it made perfect sense that the prototype nursery Goldfinger and Medd designed should be installed in a private household. The Abbatts entirely understood the power of showing a wider audience the design in a real setting. The toys, naturally, were designed by the Abbatts. Goldfinger was also creating furniture for his own home, such as an incredibly clever children’s table that expands as a child grows. He also designed a climbing frame known as the Abbatt Frame, which remained in production well into the 1960s. What was clear was that the Abbatts were now becoming manufacturers and took premises at 94 Wimpole Street in 1936. They asked Ernö to design the interior, exterior, and some of the furniture. That very connected relationship continued into 1937 when Goldfinger was commissioned to create an exhibit for the British Pavilion of the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques de la Vie Moderne in Paris. The exhibit was called The Child; the Abbatts supplied the toys. Interestingly, people were thinking about Goldfinger as synonymous with designs for childhood, a far cry from his persona in the late 60s.

The Abbatts’ role in Goldfinger’s pre-WW2 emigre life cannot be underestimated; they were his main client. They also commissioned several other refugees who would almost certainly have been in Ernö’s circle. Like the Prichards, they played an important role in bringing modern ideas into mainstream society and meaningfully helping people fleeing persecution.

Willow Road Hampstead Image Steve Cadman CC BY SA 2.0

Willow Road

In 1936 Ernö and Ursula were captivated by a plot of land located in the sleepy artsy colony in the heart of Hampstead. There were some insignificant buildings on the plot, and using Ursula’s inheritance, they decided to develop the plot, 1-3 Willow Road; their rationale was two-fold: to give themselves a family home and to showcase Goldfinger’s ability as an architect. Their first idea was to build a block of flats but that didn’t get planning permission. Their second idea was to create what would become No 2 Willow Road. The project can be technically considered one of Goldfinger’s early substantial architectural ‘commission’ as earlier projects had been for shops such as the one for Helena Rubinstein, a small shop in Hampstead called Weiss and the Abbatts’ business on Wimpole Street.

Ian Fleming

The development of Willow Road brought Ernö and Ursula directly into the sightline of the creator of James Bond, author Ian Fleming, who, with a group of locals, vehemently disagreed with the proposal to redevelop the site. Fleming challenged the plans, and an ugly battle and the outcome ensued. The house was built (Ursula and Goldfinger could deliver their own big guns to speak up for their project). More than twenty years later (grudge-nursing is simply not healthy), Fleming ensured his views were not forgotten when he chose to name the arch-villain in his new James Bond novel, Goldfinger. But there is also an alternative take on this story: Fleming bumped into a member of the Blackwell family at a local golf club, bare in mind his life had crisscrossed with the Blackwells in Jamaica (Ursula’s family were numerous and influential) – triggering him to remember his spat with Ernö years earlier and also delivered a terrific name for a baddy – Goldfinger. Whilst the Bond villain looked nothing like Ernö, given how unusual a name it is there are no surprises that the issue found its way to court. The trio of Ernö, Ursula and Ian came to a landing place and settlement; one can only assume that Goldfinger hoped that the book would ultimately slip away unnoticed – lost in the mists of time.

Ernö continued working on other projects with the Abbatts and Mary Crowley. Britain was now engulfed in war and Ernö and Mary were looking at experimental building designs. There was a lot of concern nationally about the potential sudden need for temporary housing. Baked into that, for Goldfinger, was a genuine concern about the welfare of children who would find themselves displaced from their parents. One idea they came up with was called the Expanding Nursery School. What was clear was that at some point in the future, building programmes and regeneration would begin. The assumption that Britain would win the war and that recognisable normality would return was baked into the thinking; it was quite early in the scheme of things to come to that conclusion.

Aid for Russia Fund

The Goldfingers’ ‘war’ found them immersed in local emigré and British artistic circles. However, as far as employment as an architect or interior designer was concerned, the opportunities were practically zero beyond the Abbatts’ commissions once the war started. When the Soviet Union changed course to fight with the allies, Erno, who still harboured a connection to communism, focused on furthering understanding of Soviet-British cooperation by creating small exhibitions. In 1942 he held a fundraiser at their Willow Road home, for the ‘Aid for Russia’ fund of the National Council of Labour. According to the National Trust, Goldfinger bid and won a head made by Henry Moore made of elm and string.

By 1944 British Government departments were preparing for life beyond the war and Goldfinger and Blackwell were commissioned to create ‘Planning Your Neighbourhood: for Home, for Work for Play’ a series of display boards for the Army Bureau of Current Affairs and the Air Ministry Directorate of Education Services, these showed the potential for a reimagined London and beyond, with green space, organised traffic, planned housing in a ‘vertical city’. This vision for a better city would provide housing with indoor toilets as the norm and schools designed to nurture the health and well being of the next generation. Clearly, this is a more recognisable Goldfinger for the post-WW2 world.

Finally, when the war was over and rebuilding a shattered country began, Goldfinger received a small number of commissions. Who knows, perhaps his left-leaning sympathies may have contributed to his 1947 commission to build the new headquarters for the British Communist Party. Another project in the same year was to build the offices of the Daily Worker Newspaper, the paper was created by the Communist Party of Great Britain and is today known as The Morning Star.

Elephant and Castle

In the late ’50s to mid-’60s Goldfinger changed the landscape in Southwark when he was commissioned by local government to build the RIBA Bronze award-winning headquarters of the Ministry of Health in Elephant and Castle, known as Alexander Fleming House. Like later buildings, it was a distinct divider of opinion, though to get the best sense of its beauty it has to be seen from the inside with its striking landscaped gardens. Comprised of four towers with linking bridges today it is listed. The Ministry vacated the building 30 years ago and now, refreshed and renovated, it is entirely residential, rebranded as Metro Central Heights, luxury living in the heart of London. What would Ernö have thought about that?

One of his lesser-known projects and an early post-war work is a block of residential flats and studios built for the Regents Park Housing Society (1954-56) at 10 Regents Park Road, today this small block built on a mid-terrace bomb site is Grade II listed.

Various other projects came to fruition including Haggerston School in 1964-65, and Teesdale House, which is sometimes known as Perry House in Windlesham which was built for Jack Perry 1967-69. The house is said by Historic England to be the only post-war Goldfinger home, and in the heart of the west end of London, there’s a little gem at 45-46 Albermarle Street built on the site of the bombed wreckage of two Georgian houses. Today it is Grade II listed, and according to Historic England;

The façade grid follows the ‘Golden Section’ proportions (a mathematical ratio, fundamental to classical design, that has defined proportions in both art and architecture), a principal which Goldfinger derived from his mentor, the French architect Auguste Perret, and which he applied throughout his career. While treated as a single composition, the building comprised two separate premises for different clients, and was designed to enable the floors to be interlinked laterally by constructing the dividing wall as two independent walls. Goldfinger also designed the shop and office fittings for No.46, which do not survive. The building was widely reviewed following its completion, eliciting considerable praise for its sensitivity to its historic context.’

Balfron’s service tower Image Howard Morris

Carradale House, Poplar Image Howard Morris

Balfron Tower, Carredale House and Brownfield Estate

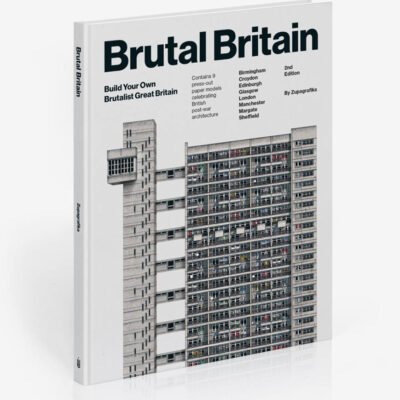

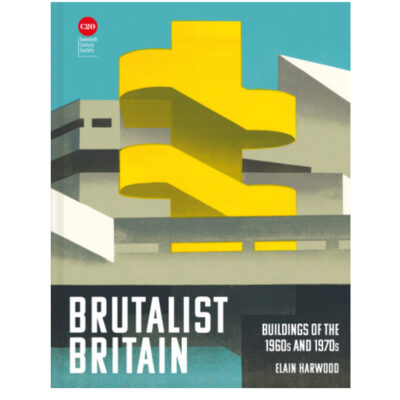

But head and shoulders above everything else built by Goldfinger sits Balfron Tower with its neighbours Carredale House and Brownfield Estate in Poplar, East London (1965-67) and Trellick Tower by the A40 flyover in West London (1968-72), two key social housing projects in London which are today celebrated and listed. Perhaps they are the truest physical manifestations of Goldfinger’s early political views about how we should live and the importance of developed, well thought out social housing. Goldfinger was wholeheartedly committed to making these homes work for local communities and even went so far as to live in Balfron for several months to ensure any problems were ironed out. Of course not all the problems were resolved which becomes clear from Ernö and Ursula’s letters and notes held in the RIBA archive at the V&A. The couple were roundly criticized by some people for behaving like true elites, observing the residents as if they were in some sort of sociological experiment and equally praised by others for making the effort to really understand what it was like living with and a large concrete highrise. The elites tag was not helped by Ernö allegedly attending meetings typically with a cigar in hand and a glass of whiskey.

What marks out these two listed estates, sealing Ernö Goldfinger’s place in architectural history is the complicated intertwined love/hate aspect to their bold design, reminiscent of a citadel, dominant and domineering, demanding of attention. They became part of a group of go-to examples about all that was wrong with the policy of putting social housing tenants in concrete tower blocks. Timing can be everything, and shortly after Balfron was completed, a tragedy became a major turning point in public opinion about ‘large panel system dwellings’, the disaster at Ronan Point in nearby West Ham. It collapsed in 1968 shortly after completion, due to a gas explosion. This was not a Goldfinger design but it started a wide-ranging discussion in the mainstream press about the very real problems of living in a high rise, not just social but in some cases structural. That conversation has very real connections to Grenfell Tower. Goldfinger did not build another housing estate.

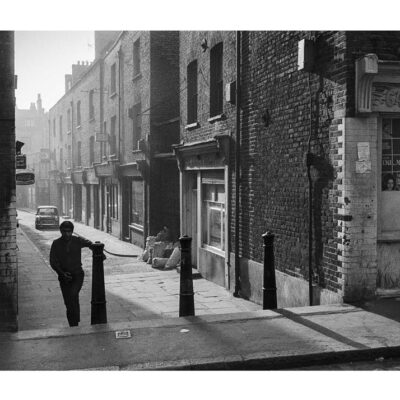

High Rise JG Ballard

For decades Balfron, Trellick and the like informed what Londoners thought about what it might be like to live in a concrete tower block. they were the fodder of filmmakers looking for depictions of isolation, lawlessness and decline. They also defined several generations opinion about Goldfinger’s contribution to London architecture. The high-low point for inner-city concrete tower blocks came in the form of JG Ballard’s 1975 book, High-Rise. Whilst the story was actually about the other end of the scale – private ownership in a luxury block – the storyline of people who descended into what one critic described as ‘primitive, feral chaos’ played well to the anti-Goldfinger brigade.

Meanwhile, Goldfinger lived in leafy Hampstead only a few miles from the estates. He continued to receive commissions but was fully aware of how misunderstood his housing estates were and how little support the tenants were receiving from the local councils, there was little he could do about this.

Trellick Tower: Image Louise Loughlin ©

The change did eventually came in the public consciousness and with it, a full appreciation of Goldfinger’s brilliance, when brutalist architecture began to be meaningfully celebrated for its brut, unadorned concrete beauty. Balfron and Trellick were understood in the context of other estates across Europe built by important modernist architects. such as Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation in France and Germany and Chamberlin, Powell and Bon’s Barbican Estate in the City of London. Goldfinger’s moment had come, too late for him personally, he died in 1987.

However, the appreciation of the architecture also came in the aftermath of the collapse of the housing market, cash-strapped local councils realised that there was the potential to actually sell Goldfinger’s vision to a new generation rather than shoulder the massive renovation costs themselves As I write these estates are slipping into full-blown private ownership. It’s hard to imagine Ernö and Ursula approving of this, whilst they would have enjoyed the celebration of Goldfinger’s design they would have struggled with the loss of social housing to the private sector.

One cannot help but wonder how Ernö would have responded to his celebratory status had he received the attention he would now have from the public and the accolades in his lifetime. Perhaps a fulsome and direct riposte?

Ernö Goldfinger 1902-1987

Image Ernö in front of Trellick Tower 1972 photo Sam Lambert RIBA COLLECTIONS