Chamberlin, Powell and Bon

My Father, One Of The Men Who Designed

The Barbican

Memories, as the daughter of Geoffry Powell of

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, architects of the Barbican

Polly Powell in conversation with Lucy Morris

Image Vaughan Grylls ©

Image Vaughan Grylls ©

As the 50th anniversary of the arrival of the first Barbican resident dawns, Greyscape sat down with publisher Polly Powell. Being the daughter of Geoffry Powell, one of the three founding members of Chamberlin, Powell and Bon. Polly is in a unique position to give an oral history of her father, the other partners and the Barbican in her own words.

At what point did you become aware of the importance of the Barbican and your father’s role in its creation?

My earliest memory of realizing that my father was involved in something important was when I was 11-years-old. I was at primary school and I distinctly remember that my parents came to a school event and the other parents were trying to talk to my father. I thought, ‘This is odd, this is not supposed to be the case.

As I grew up and went to Manchester University and met architecture students, I began to realise the significance of the Barbican.

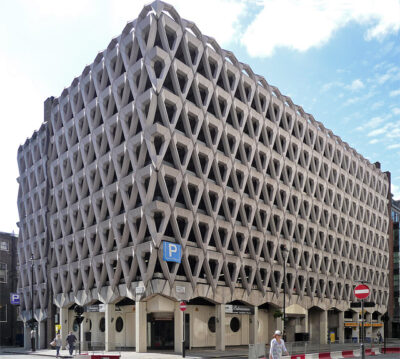

Frobisher Crescent

The Barbican excited very different opinions from huge admiration to harsh criticism, what was that like?

The negativity about the Barbican started almost overnight. It went from something to be proud of to something I was very careful about – who I said what to. It could unleash a lot of negativity. The Barbican Estate was in my family’s DNA, it was very close to our hearts and we felt those attacks. They were enormous and relentless.

As the Barbican was 30 years in the making it was always going to be out-of-date by the time it was built. Plus, the Barbican administration, for whatever reason, did not defend the estate at the time. So it was out of fashion and easy pickings for anyone to criticise.

Ben Jonson House

When did that change and what was that like?

It was around 1997 when slowly, very slowly, people started asking my father to give talks and interviews. He had been somewhat overlooked for 15 years – no one had much interest in any of the architects; not just my father but his partner Christoph or Jean Chamberlin, the widow of fellow architect Joe Chamberlin who was still alive and part of the practice.

What a truly wonderful thing it was to begin to witness the new love for the Barbican. We just saw the shoots of it when my father was alive. I remember him saying,

‘You know, it’s going to be listed.’

It was astonishing that the Barbican would be listed.

What would you say your father thought about all of this?

Shortly before my father died, I bought a flat in Golden Lane. I have pictures of my father standing on the balcony looking across Golden Lane and the Barbican letting a sigh of

‘it’s alright, it’s okay’

Geoffry Powell Golden Lane

You can’t imagine the criticism and negativity prior to it being listed. For him, it all coming good must have been such a wonderful moment.

Tell us a bit about your father’s outlook.

My father was very forward-looking. He wasn’t in any way stuck in the mud but he liked a range of things, including classic cars. His first car was a decrepit Lagonda that was famous because

‘some of the Barbican plans accidentally fell through the dilapidated floor

and bounced along the road’.

But, at the same time, he would embrace Modernism. For instance, my parents lived in a cottage but they transformed it into an open living space with PVC curtains, it was very 1970s.

Barbican Lake © Greyscape

In his work, he referenced lots of architects, Corbusier, Hawksmoor, Lutyens, Mies van der Rohe.

“He travelled abroad with Jean and Joe Chamberlin and Christoph Bon and looked at Roman and Greek archaeology- you can see it in the water fountain in the Barbican Centre and the monumentality, the classicism of the estate’s architecture”.

The spaces in-between buildings were also a great inspiration. They were all keen on London’s Georgian squares with the landscaping. My parents first family house was in Holland Park and Jean, Joe and Christoph lived on South Edwards Square. They all lived with these communal gardens. It is interesting,

“the trees and plants were just as important as the bricks and the mortar and the open spaces were as important as the built spaces”.

What were the motives of the Corporation of London in backing the building of the Barbican?

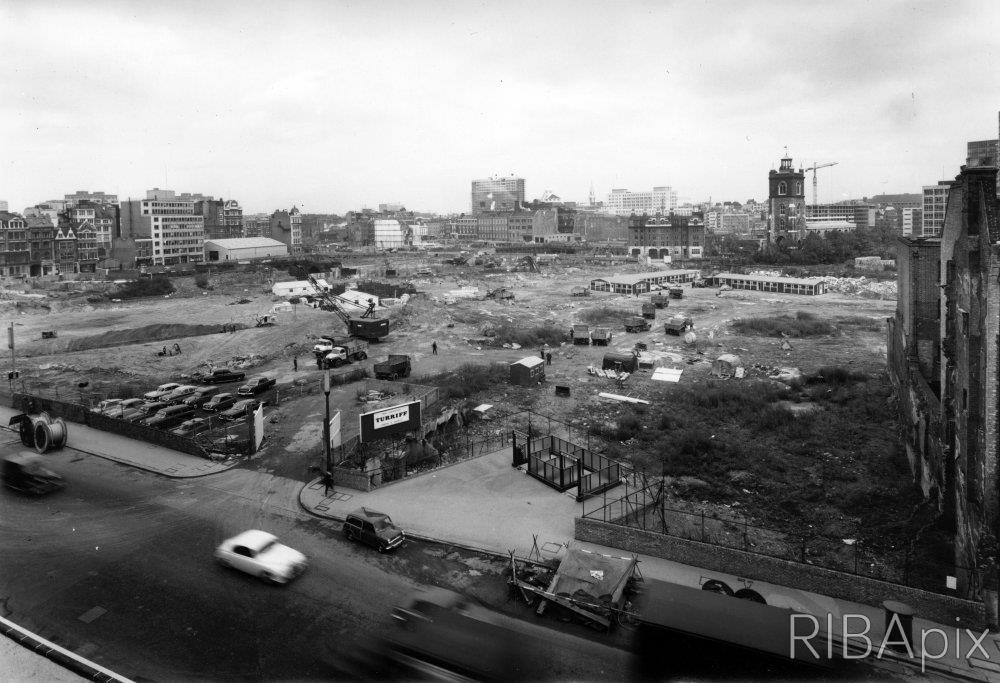

John Maltby / RIBA Collections

There was a political dimension to the Barbican, of course. The Barbican was built for working white-collar people in the City of London. It was never a social council estate in the way that Golden Lane was. Cynically, it was about supplying housing for the City of London as the City of London was worried they were going to lose an MP if not enough people were actually living in the area.

Also, the Corporation of London was a huge employer in the ‘70s and ‘80s so it needed housing for single people living in their own apartments. This was rare before the Second World War –

“the Barbican was a new kind of life for independent people not necessarily

the old fashioned family units”.

Barbican Site Under Construction 1963 John Maltby / RIBA Collections

And what were the values and aims of your father and his two partners?

The firm was driven by an idealism for homing people. Pre-war, a lot of people were living in very difficult conditions, with loos outside and many families living together in flats. Post-war, the building of new homes was about making better homes too, with things like built-in cookers and waste disposal systems such as the Barbican had.

Geoffry Powell and Jean Chamberlin at the official opening of the Barbican Centre 1982

There was a collective responsibility for Chamberlin, Powell and Bon. Historians are constantly trying to unpick who did what. I wasn’t there so I can’t say who worked on what but I can say there are certain projects where there were lead architects. Joe Chamberlin designed the Arts Centre, Christoph Bon concentrated on the detailing, whilst my father worked on the residential bits.

The three architects worked together on the top floor of their studio together – they were friends, they holidayed together and had lunches together so it was more than a working relationship. When I look back on my own professional career,

“the idea that they had a partnership that went on for 35 years, that built the Barbican estate and concert hall and still have Sunday lunch together is really very wonderful and impressive.”

This monologue is taken from an interview with Polly Powell and has been condensed for the feature.

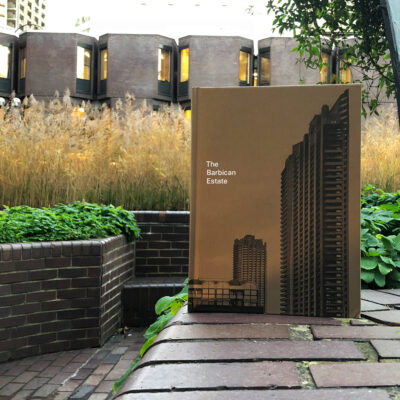

Barbican Estate © Greyscape

Geoffry Charles Hamilton Powell born into an Indian Army Family in Bangalore, India, November 7 1920, died December 17 1999

Polly Powell is the publisher and owner of Pavillion Books, amongst her recent publications about Architecture and Design:

Isokon and the Bauhaus in England

Art Deco in Britain (Oct 2019)

Images with thanks to Polly Powell ©

Lucy Morris is a Journalist and Brand Strategist and former Barbican resident www.instagram.com/lucyalicemorris/