Claude Parent

Curating the legacy of a visionary architect

Claude Parent 2014 © Emmanuel Goulet

Where do you even start when you are faced with a ‘colossal’ volume of materials to catalogue and digitalise? The problem designers Chloé and Laszlo Parent face is to some degree self-inflicted but we all end up the beneficiaries of the work. Claude Parent, a man who went his own way, bringing the oblique angle into the language of architecture, produced a huge body of work in his 70-year career.

Interviewed by Greyscape, the celebrated French architect’s daughter and grandson describe their relationship with Claude, who died in 2016, his collaboration with Paul Virilio (ending in consequence of the 1968 Paris riots), his influence on a new generation of architects and their book Claude Parent — Visionary Architect.

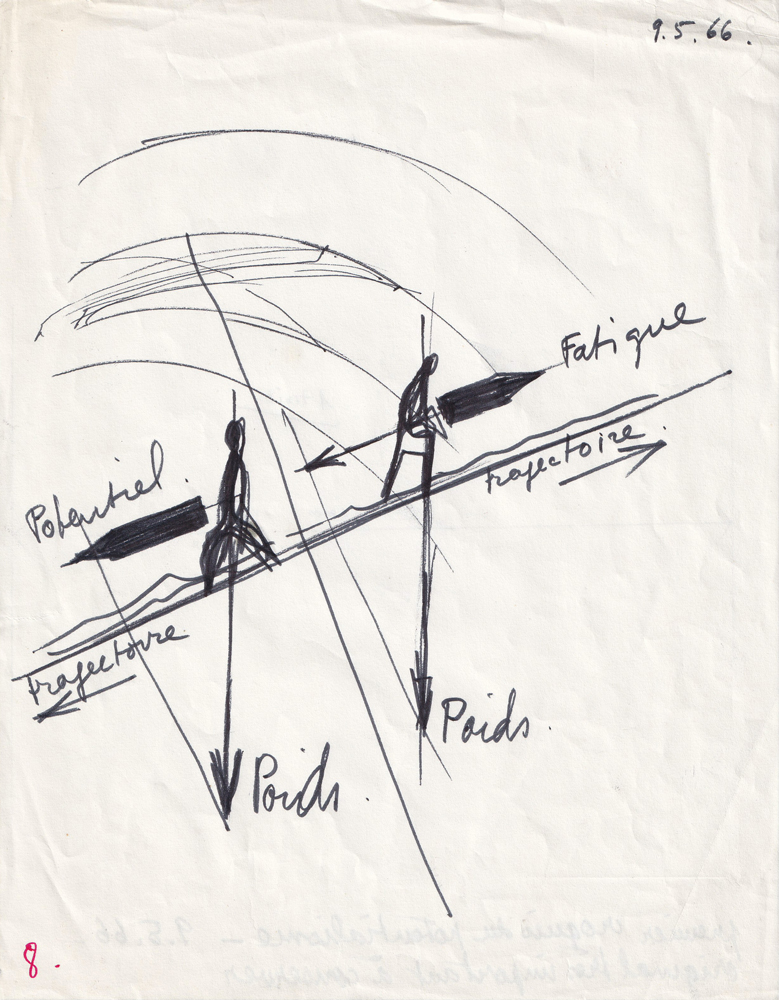

Le Potentialisme Claude Parent Archive ©

And where better to start than clearing up the meaning of a certain key expression:

… Fonction Oblique

Fonction Oblique is an architectural theory conceptualised and developed by architect Claude Parent and French philosopher Paul Virilio as early as 1963. Claude Parent continued pursuing the approach in many of his projects (built or not) including his own home after his collaboration with Virilio ended in 1968. The central concept of Oblique Function is the tilting of floors and walls to open up the enclosed space rather than limiting and closing it. By creating an architecture using ramps and slopes as main vectors and structures it made surface more important than space. The theory rejected the orthogonal rule (that objects or vectors should be perpendicular to each other) and was a break from modernism and its orthogonal vocabulary. Oblique Function was revolutionary and changed the way we live in and experience public and personal space. It’s also a theory that considers the effects of ramps on the body (dynamic vs. static, effort vs. ease, experiencing unbalance vs. stability). It envisions new human and social interactions by transforming the urban landscape as well as the habitable unit: ramps allow city dwellers to walk freely above or under the habitat, without being stopped by a vertical obstacle. Lastly, the theory changes the relationship between the site and the city by incorporating it harmoniously in the natural landscape, without interrupting it or destroying it, but rather by unfolding it gently above.

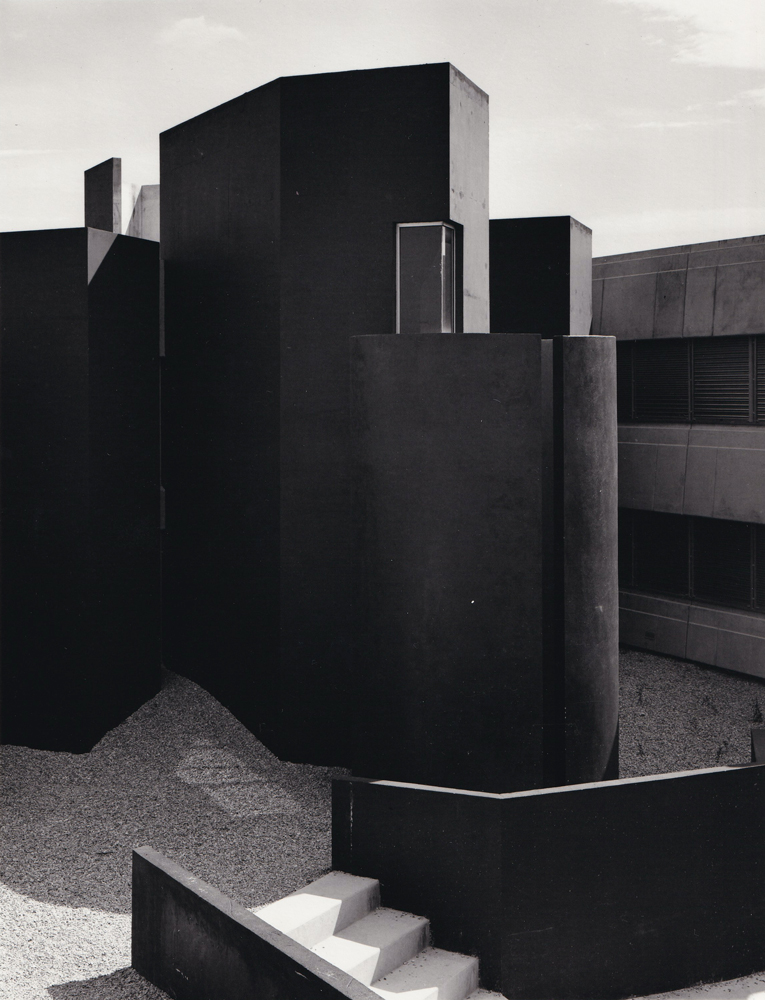

Commercial Centre Sens Image Giles Ehrmann ©

Would Claude Parent recognize the label ‘radical’, which often prefaces his name?

At the time of his breakthrough work, Parent was labelled an “experimental architect” or “utopian” (a term he disliked because utopia “expressed the notion that it wouldn’t be built”). The word “radical” has been more recently associated with his name, and Parent accepted that. But he never really agreed with labels (brutalist, deconstructivist, utopian, etc…). The only title that Parent claimed mattered to him, was the one of “architect”. A title he had to fight for when he dropped out of the Beaux-Arts school without a diploma, revolted by its outdated academism. It’s only in the mid-60s that he was awarded the title by the French Architectural Board (Ordre des Architectes) which had finally acknowledged that not only he was indeed an architect but also contributed greatly to the reputation and status of French architecture through his projects and writings.

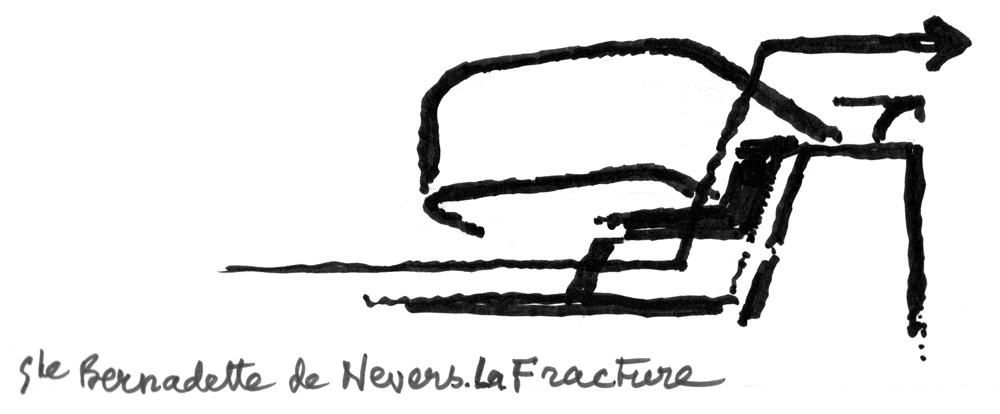

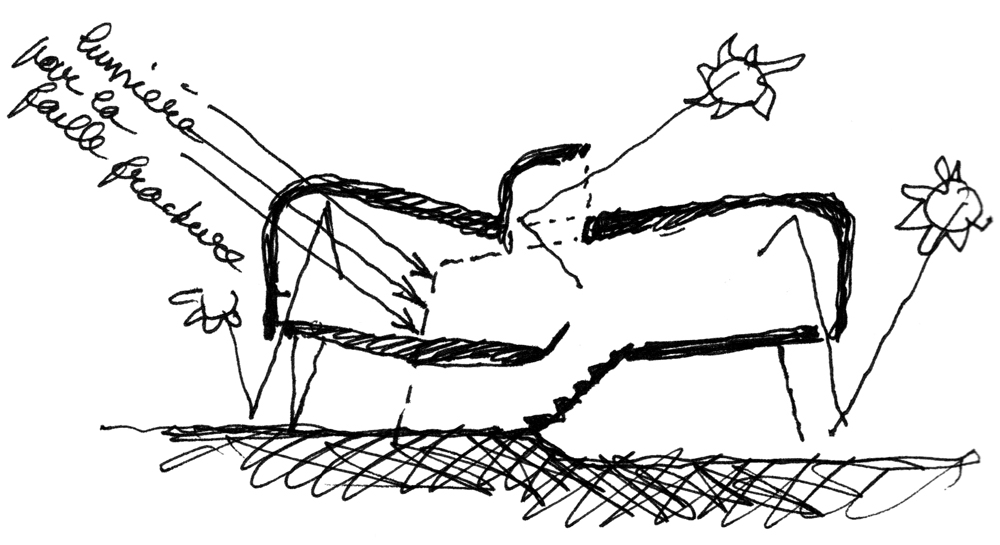

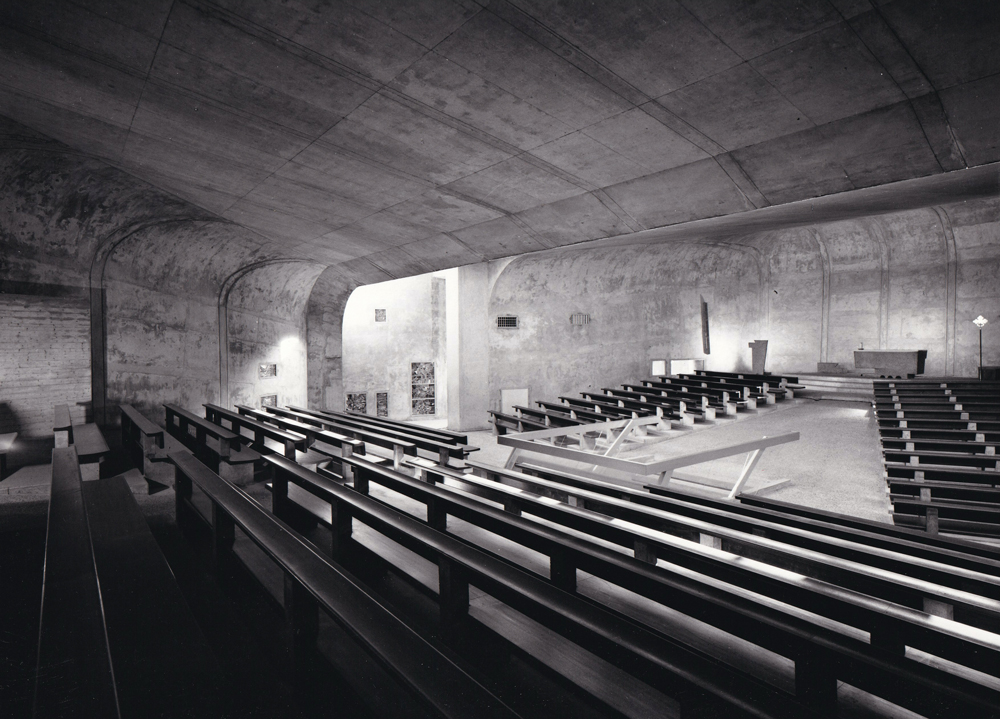

Sketches of Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay church, Nevers Claude Parent Archive ©

Sainte Bernadette du Banley, Nevers © Gilles Ehrmann

Did you know him well?

Yes, we were both very close to him and he transmitted to us his love of architecture, drawing and concrete!

Was Parent aware in his life time that he had been cited as an influence of so many highly regarded architects?

Yes, he was aware of this (often in disbelief, sometimes even amused by it), especially from the mid-2000s until his death in 2016, as more and more people regarded his work as groundbreaking and pivotal. His built work and extraordinary drawings were being re-discovered by a new generation, and many of those who had originally tried to disassociate from him, finally wrote about his influence. Jean Nouvel of course (“his spiritual son”) but not only. Outside of France, where people were less shy to acknowledge that his work was fundamental, architects, such as Daniel Libeskind, Thom Mayne, Frank Gehry, Wolf D. Prix, Michele Saee, Zaha Hadid and more, talked about his direct influence and the importance of the Oblique Function. Rem Koolhaas even paid tribute to Claude Parent in the RAMP section of his “Elements of Architecture” exhibition when he curated the Architecture Biennale in Venice. This was of course very important to Claude who had faced criticism or rejection from his peers for so long. The 2010 retrospective at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine in Paris, curated by Francis Rambert and Frédéric Migayrou and designed by Jean Nouvel, confirmed the unique position of Claude Parent in the history of architecture. His induction to France’s Fine Arts Academy was also an important milestone in this public and professional recognition. Now institutions, students, architects and artists from all over the world contact us to know more about his work. We are grateful that he could witness this change during his lifetime.

La Ciotat, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, © Pierre Bérenger

To what degree was his vision, which now seems aeons ahead of its time, understood when he was practising as an architect?

At the time when Claude Parent and Paul Virilio started conceptualising, writing and implementing the Oblique Function, and later when Parent continued to develop and apply this theory by himself, it was mostly viewed as a curiosity with no future, an eccentric, irrational theory. Even in the architectural world, few architects paid attention and understood the extraordinary value and power of this new theory. Even fewer people in the general public were interested. But that would not stop him from believing it was the necessary direction for architecture (which was looping in its own fossilising system) and he was right, of course. There were architects who acknowledged it, even in its infancy, such as Bruno Zevi, Juan Daniel Fullaondo, Peter Cook, Hans Hollein and a few more who were involved in what was called “experimental architecture” at the time. A few other personalities in the cultural world, even people like the Abbé Bourgoin who defended the Saint-Bernadette du Banlay church against its detractors. But the general reaction back then was not so supportive of the Oblique Function.

Who were Parent’s contemporaries at the École des Beaux Art?

His friend and colleague Ionel Schein whom he met in 1949. It’s with Schein that he opened his first studio and their partnership lasted until 1955. They were both so outraged by the academism of the Beaux-Arts school, that they left before getting their diplomas and started practising architecture on their own. Claude also briefly worked for Le Corbusier but ended up frustrated by the whole experience.

Can you describe his relationship with the Groupe Espace?

The Groupe Espace was founded by André Bloc and Félix Del Marle in 1951 and gathered artists, architects and engineers together. I think Nicolas Schöffer, who was part of the group, introduced it to Parent and his colleague at the time Ionel Schein. After the pair wrote a letter criticising the group for not talking about the younger generation of architects, Bloc invited them to participate. For Claude, it was the start of a 15-year collaboration lasting until Bloc’s death in 1966. Claude discovered and worked with many abstract artists of the group, which shared his experimental visions and desires of freedom, and these artists also contributed to some of his buildings (for instance as mosaics artists or colourists). He later broke away from collaborating with artists because he wanted to reaffirm that architecture and art are not the same disciplines (many artists in the Groupe Espace wanted to do architecture) but he always left the door open for some of them to collaborate.

Villa Drusch, Versailles © Joly & Cardot

Villa Drusch, Versailles Claude Parent Image Christopher Iwata ©

Can you explain more about the collaboration with Paul Virilio and why did that end?

Claude, who had already experimented with the oblique in some of his projects like the Villa Drusch, met Paul Virilio through his long time friend, painter Michel Carrade. Speaking together, they realised that they had the same interest in tilted bunkers, ramps, speed, and contemporary architecture breaking away from modernism. Together, they envisioned the Oblique Function theory and founded, with Carrade and sculptor Morice Lipsi, the Architecture Principe group and the manifesto of the same name. Virilio, a photographer and philosopher, who was also a stained-glass master at the time, was passionate about urbanism, something that Claude had already worked on for his projects (Les Villes Cônes, 1960, with Lionel Mirabaud, Paris Parallèle in 1959 with André Bloc) or when collaborating with artists like Yves Klein or Nicolas Schöffer). Parent and Virilio produced some exceptional work together, including the Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay church in Nevers, which is now registered as a Historical Monument. The split happened after the student-led protests of May 1968 in Paris. Virilio wanted to get involved in politics and started organising protests with the students of the Sorbonne. Claude, who was never interested in politics and had a certain distrust of politicians, did not want to follow along. He was sympathetic to the students’ movement, but this was not his battle. He fought for his vision of architecture and he wanted to keep this focus. This put an end to their collaboration, but Claude said several times that he never had such an intense and productive collaboration as the one he had with Virilio.

Was he involved in creating the archives?

No, he wasn’t. He was never preoccupied with this kind of endeavour. The archives were started a long time ago in an informal way by Claude’s wife, Naad. She put together all the press books starting from 1959, when they got married, and neatly organised and categorised every document in little black boxes still around today. Claude had donated the majority of his architectural plans, models, photos and early drawings to the IFA (Institut Français d’Architecture), the Centre Pompidou and the FRAC Centre. We are now digitalising and recording all the work, publishing books, organising events, meeting researchers and students, participating in exhibitions around the world to present Claude’s work and the book (recently at SCI-Arc Los Angeles, Vitra Design Museum, MAXXI Rome, Casablanca School of Architecture) and hopefully more in the near future…

Venice Biennale, French Pavilion 1970 © Gilles Ehrmann

How did you approach tackling such a large body of work and making it accessible?

There is no simple way. Claude’s architectural production may not seem enormous at first glance (although it is in fact very substantial), but the scale of his graphic work and written work is colossal. At the moment we are focused on creating a database of his drawings and sketches, which we have recorded over one thousand of so far.

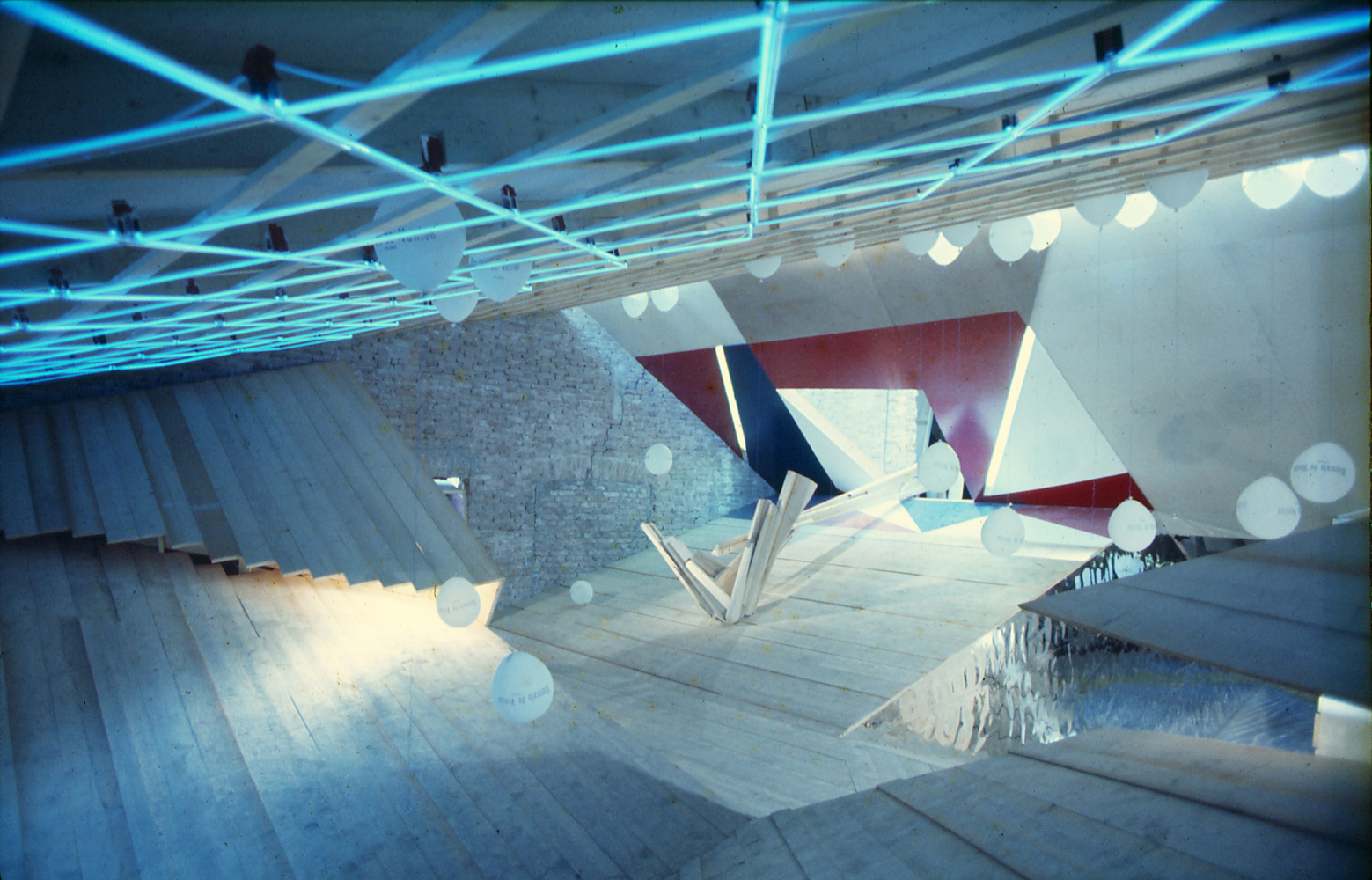

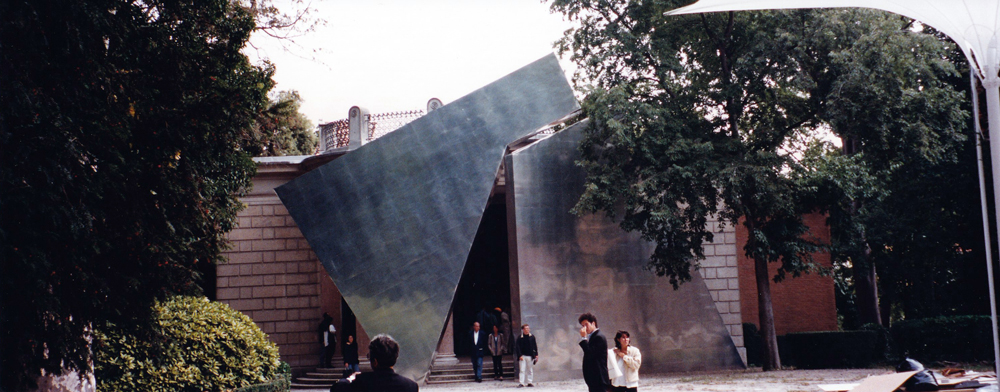

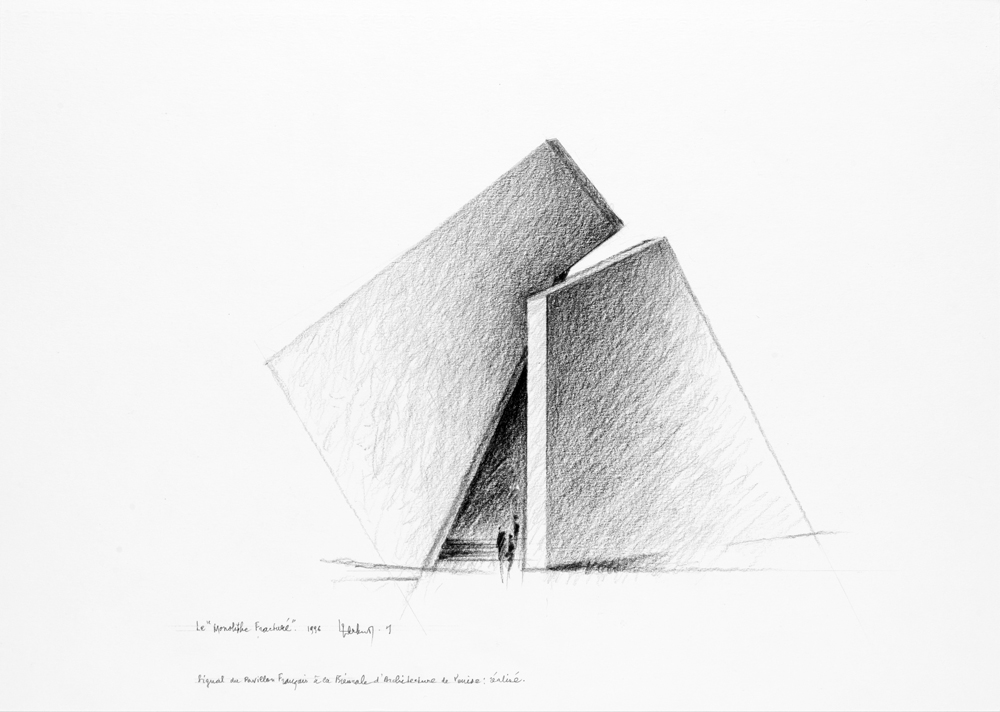

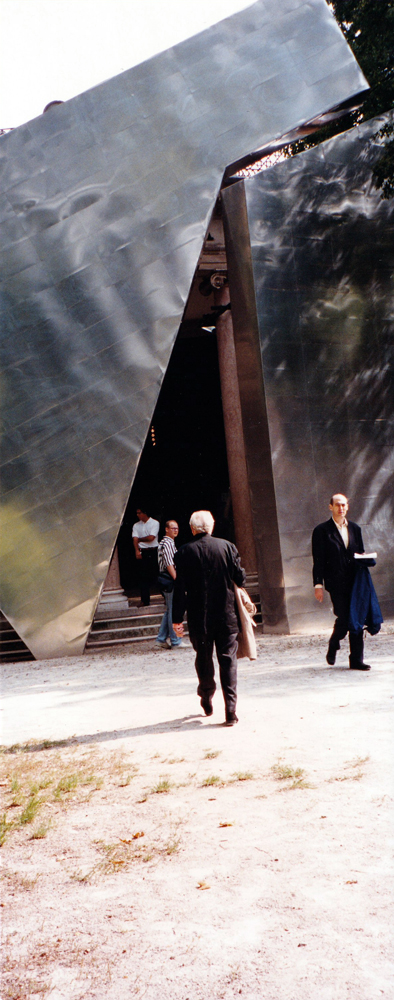

Let’s talk about the Venice 1996 Architecture Biennale

Frédéric Migayrou, who was at the time director/curator in chief of the FRAC Centre in Orléans, was chosen to curate the French Pavilion at the 1996 Venice Architecture Biennale. Frédéric was the major force in establishing the connection between Claude Parent’s work and contemporary architecture. He showed clear evidence of the lineage, establishing Claude’s work historically but also in connection with younger architects by demonstrating its importance and influence. We owe him a lot for bringing this legacy, or “paternity”, into the spotlight. But in the ’90s he was probably a lonely voice. Although a rising generation of French architects such as Odile Decq and Benoît Cornette or Frédéric Borel knew his work, read his books, went to his lectures and acknowledged his influence, it was never documented or established historically. Frédéric Migayrou’s French Pavilion gathered them all under the same roof, showing everyone that Claude was indeed the disruptive factor, the architect who made the change happen, breaking away from modernism to open the way for one of the most creative forms of contemporary architecture. He also asked Claude to design the grand entrance of the Pavilion (otherwise an unremarkable neo-classical building) while Odile Decq and Benoît Cornette were in charge of the exhibition design and scenography, creating a particular space in which this legacy was even more obvious. They were rewarded with the Biennale’s Golden Lion for their work.

Monolithe Fracture, Venice Biennale 1996

Venice Biennale, French Pavilion 1996 © Naad Parent

Writing the book

One of our long-time projects was to publish a book about Claude Parent’s drawings and graphic work in English. With the support of the LUMA foundation, fashion designer Azzedine Alaïa and publisher Rizzoli New York, this book finally exists. It contains the personal written contributions of many architects close to Claude, such as Jean Nouvel, Frank Gehry, Odile Decq, or Wolf D. Prix. It was not easy to make a selection though, as there are hundreds of inspiring drawings and sketches that we wanted to show. We had to narrow down the selection to some of the most iconic ones, ranging from the 1960s all the way to 2016, with many never seen before. Our intent was also to have Claude’s own voice about his drawing process and mindset introducing each section. So we researched his books, articles and interviews to provide the reader with an insight into what drawing meant to him during each period of his life.

Do you have a favourite ‘Parent’ building or design?

Too many: Villa Drusch, Maison Bordeaux-le-Pecq, Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay church, Villa Bloc in Antibes, Fondation Avicenne (previously Maison de l’Iran), the supermarkets in Sens and Ris-Orangis…

Villa André Bloc, Cap d’Antibes Image Gilles Ermann ©

Fondation Avicenne, formally Maison de l’Iran at ‘CiuP’ Paris Claude Parent Archive © Gilles Ehrmann

Your favourite architectural styles?

Brutalism, Bauhaus, Modernism, Constructivism, Deconstructivism, Art Deco, Art Nouveau, Japanese Metabolism, Industrial, Experimental and Radical architecture.

Your home city

We share our time between Paris (where the archives are located in Claude’s Studio), Los Angeles and Casablanca.

Discover the Claude Parent family archive:

Insta: @claudeparent_architect

Facebook: @claudeparentarchitect

Claude Parent 1923- 2016

Claude Parent — Visionary Architect Rizzoli New York