Interview with Barnabas Calder

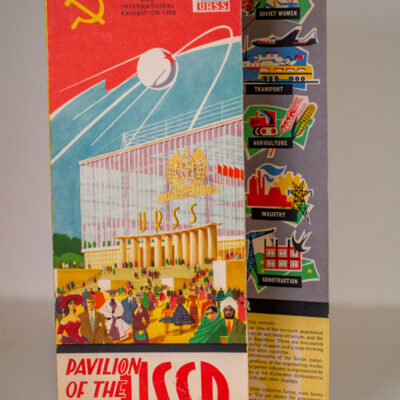

Dr Barnabas Calder, author of the seminal Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism has, in his latest book, Architecture: From Prehistory to Climate Emergency? set architecture and construction in an aeon spanning perspective leading to the human race’s existential climate emergency and architecture’s role in causing and solving the crisis

©B.Calder

‘from Uruk, via Ancient Rome and Victorian Liverpool, to China’s booming megacities… from the Parthenon to the Great Mosque of Damascus to a typical Georgian house’ along the way explaining how each was was influenced by the energy available to its architects, and why this matters. There is a direct line between buildings and energy consumption and the climate crisis we find ourselves in’.

Greyscape asks;

Why this topic, now? You’ve written a sweeping history, full of fascinating detail, and the connections between building design and construction, political, economic and social history and its role in changing the world’s climate.

We stand at a crossroads in history, where, if we don’t take the path to rapidly reaching zero carbon, we are likely to be remembered by the few remaining generations of humans as the people who knowingly connived at the destruction of all that was good about our planet. If we do take the necessary steps, in particular escaping from our dependency on burning fossil fuels for energy, we will have achieved the most important collective act in human history.

Knowing how vital energy is to architecture today (39% of greenhouse gas emissions come from constructing and running buildings) I wondered how energy and architecture had been related in the past. In 2015 I did a quick back-of-an-envelope calculation for the biggest monument of the ancient world, the Pyramid of Khufu – over 5 million tonnes of stone, requiring a decade or more of hard work from perhaps 20,000 labourers at once. To my shock, I found that all that work amounted, in energy terms, to less energy than any seven average modern American citizens will use in their lifetime at current rates. The most powerful human on the planet in 2500BCE had only as much energy at his fingertips as an American extended family does now.

From there I read lots of energy history and realised that energy – food, labour and fuel – was the biggest story not just in today’s architecture, but in all of architectural history, and that’s the story I tell in the book, from ancient mammoth hunters’ homes – the earliest architecture known anywhere – through to today.

How did you become a historian of architecture?

My parents used to take me to old churches and stately homes as a child, and it just clicked – I’ve always been drawn to buildings, initially as a child by finding them beautiful, with intellectual curiosity about them growing over the years that followed. I’ve been amazingly privileged to be able to make that into a career.

The story of architecture is the story of humanity. The buildings we live in, from the humblest pre-historic huts to today’s skyscrapers, reveal our priorities and ambitions, our family structures and power structures.

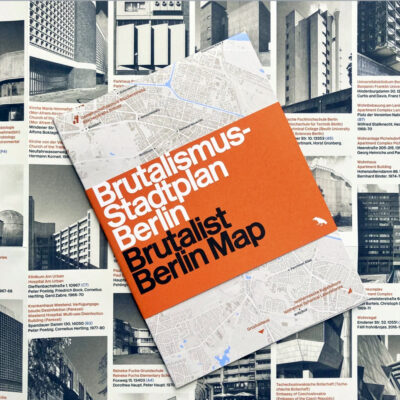

Of the many you’ve written about, is there a building that stands out as a perfect example of Brutalist and Modernist design

I don’t associate the word ‘perfect’ with Brutalism. ‘Perfect’ suggests completeness, order and essentialness when for me the joy of Brutalist buildings is their diversity, their punch, their messiness, their incomplete attempt to achieve a whole new world starting from each new project. It’s absolutely the architecture of a moment when no one realised the harm fossil fuels were doing, but architects could see the revolutionary improvements coal and oil were bringing to human life. Fossil energy furnished the miracle materials concrete and steel, which could make any shape and size of building possible, and the powerful, reliable servicing which meant you could build great agglomerations of building like the Barbican, where the arts venues are buried deep in the ground, with roads, railways, parking, flats and gardens heaped above and around them. Yet subterranean auditoria can be safely and reliably ventilated and lit in a way that no earlier generation could have achieved.

Barbican Estate London, © Gingerhead Designs

Tell us about your project about Sir Denys Lasdun.

I was fascinated by the National Theatre as a child, not understanding why it looked like wood but felt like stone – it seemed like the result of some mythical petrification. When I came to choose a subject for my PhD I returned to it, and spent three years in archives and libraries tracing its extraordinary design history. I then went on to catalogue much of Lasdun’s archive at the RIBA, and have been working ever since on a big complete works, funded by the Graham Foundation. It’s been a huge project and I can’t wait to get it out to the public. He was a remarkable architect – brilliant, irascible, and dedicated to architecture with punishing completeness – and his archive includes an extraordinary body of memoranda that record his immediate responses to the twists and turns of his big, challenging projects as they fought their way through client changes of mind, funding and planning processes. It makes for a remarkably human and engaging story, as well as one which reaches from the heights of political powerbroking to the flats of some of London’s poorest people.

©B.Calder

A dinner in a diner – three guests plus you, and they have to be architects …from any period, who would you invite?

1. Any architect from sixth-century Rome. After the fall of the western Roman Empire the city had lost its immense grain imports from Egypt, and its population had collapsed. Farmers were using palatial ruins as barns, and the few new construction projects, like churches for a papacy growing in political power, were pulled together from dismantled older buildings. I find it a period of hypnotic interest – of destruction, abandonment, and a struggle to reinvent a proud city amongst such overwhelming built evidence of decline and retraction. I’d love to hear from an eyewitness how it felt to be in Rome whilst it fed on itself, energy-starved and riven with crises.

2. Sinan, the greatest of the Mosque designers from the golden age of Ottoman architecture. The chapter on mosque architecture in my book has left me wanting to know a great deal more, not only about the spectacular decorative arts that are the focus of so much writing about Islamic religious architecture, but also about the nitty gritty of how such big projects were organised and run – the administrative and logistical challenges were the real heart of construction then and now, and the great projects of the Ottomans have a lot to teach us. They were zero carbon, beautiful, and have lasted for centuries.

3. Charlotte Perriand. It would be amazing to meet one of the heroes of the formative period of Modernism. The 1920s and ’30s saw architects and designers bubbling over with excitement at the potential of new energy carriers (oil and electricity) to transform every aspect of how we live. They had no idea of the harm CO2 emissions would eventually do to our climate, just the thrill of starting a new architecture and urbanism based on the new energy rules. A comparable challenge lies before today’s architects, designing a zero carbon future. It would be great to have Perriand’s insights on how to change the world for the better.

What are you reading at the moment?

My next book will be a history of the ways that our energy use has shaped all of human culture, worldwide, so I’m reading an amazing diversity of stuff from evolutionary biology to archaeology and anthropology of hunter-gatherer groups to nineteenth-century food history to history of recent popular music. It’s amazingly interesting and fun, though boiling it into a clear and coherent narrative is a big challenge.

About Barnabas Calder:

Barnabas Calder is a historian of architecture at the University of Liverpool. He is author of Architecture: From Prehistory to Climate Emergency (Pelican, 2021) and Raw Concrete: The Beauty of Brutalism (William Heinemann, 2016). He is a specialist on the work of Sir Denys Lasdun and is a Trustee of the Twentieth Century Society.

Find him on Twitter/Instagram @BarnabasCalder.