Aylesbury Estate In Three Pieces

‘They call this a community

I like to think of it as home’

PET SHOP BOYS

“Single”, Bilingual

Aylesbury Estate, image Howard Morris

First Piece – The Prime Minister

‘No no-hope areas’, declared Tony Blair the new British Prime Minister in a speech at South London’s Aylesbury Estate after his sweeping election victory in 1997. His first speech away from Parliament was delivered in the modernist housing estate supposedly symbolic of Britain’s inequality, a blighted landscape of a no-hope existence. Aylesbury Estate became a cliché of British post-war social housing. Larger than the Barbican and providing homes for more than 7000 people, Aylesbury was built in the ‘70s. It was thought a failure; flawed designs, poorly constructed using poorly understood techniques and dehumanising to the socially and economically disadvantaged residents schlepped in by the statist-inclined Southwark council. Tony Blair’s New Labour wanted to condemn and replace rotting and neglected council estates and do something immensely better for the people made to live in these modern rookeries. But what eluded the well-intentioned PM was that Aylesbury was where people, good people, definitely loaded with problems of wealth and health and resources, were nonetheless making decent lives for themselves and for their families. But no one was listening to them.

In Aylesbury, we hear echoes of Pruit-Igoe, the mighty St Louis housing project that finished up being dynamited, its destruction bruited by the famous architectural critic Charles Jencks, as marking the end of modernism. The same wrong lessons were drawn from Aylesbury, proof that modernism doesn’t work, that ‘some’ people can’t live in a socially acceptable way and will ruin whatever homes are provided for them, that public housing is simply an incubator for anti-social and criminal behaviour. The voices calling out underfunding in construction and maintenance struggled to be heard above the biases of discrimination on the grounds of race and class.

Aylesbury Estate by Howard Morris

Prime Minister Blair went on:

‘Behind the statistics lie households where three generations have never had a job. There are estates where the biggest employer is the drugs industry, where all that is left of the high hopes of the post-war planners is derelict concrete. Behind the statistics are people who have lost hope, trapped in fatalism.’

If Aylesbury was in difficulty before Blair’s speech, it was in deep, deep trouble afterwards. ‘Community’ is hard to measure. The degree of empathy people feel for and identification with, one another doesn’t admit of hard metrics like numbers of people, rent rolls, the tally of broken windows and vandalism. So how do we know there was and is a community on the Aylesbury Estate? The marginalised may not have had the political voice they need or the influence wealth confers but they can make art. That’s where Harriet Mena-Hill enters the story. First, let’s describe what has happened to Aylesbury.

Highwalks, Aylesbury Estate

Aylesbury fell into the coils of a cycle of decline. As it became increasingly dilapidated and families moved out, Southwark Council filled the estate with short-term tenants, people with overwhelming problems of immigration status and mental health. Through no fault of their own, they weren’t invested and weren’t able to commit to the estate, and the decline continued with growing anti-social behaviour and crime. The estate initially brought huge improvements to the lives of the original tenants – they talked repeatedly about the light, the space, the views and the connection with their neighbours. But with the loss of the caretakers and subsequent tendering of the cleaning contracts and the introduction of temporary housing licences, the physical decline accelerated. The estate was used as a backdrop to film dramas set in a cacotopian world of abandonment and atomised society.

Over £350m would be needed to regenerate Aylesbury, money Southwark didn’t have and so it decided, in 2005, to demolish and build anew putting the estate in the hands of a housing association.

The project isn’t finished and will take years. It’s dogged by controversy, occupation by squatters and the powerful case that some of the buildings could be more easily and economically be refurbished than demolished.

Second Piece – the Artist

And so to Harriet Mena Hill, an artist trained at the famous Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts and, as Harriet observes, a school located close to Aylesbury Estate but at the same time a world away. She knows Aylesbury, her her home is close, her studio, too and in 2018 Harriet started art workshops with young people from the Aylesbury Estate.

Taplow Nocturne displayed on the Aylesbury Estate June 2021

Harriet’s work on Aylesbury began with large felts, what she calls Soft Concrete. In a painstaking process of mixing soft corredale and merino wool fibres using carders, broad wooden paddles covered in a fine, viciously sharp steel comb, and then pushing the mixed colour through the felt with steel needles, Harriet has created startling panoramas of the Aylesbury Estate in the twilight of its life. In soft felt, concrete is rendered.

Aylesbury Felting by Harriet Mena Hill

Harriet didn’t stop working with people, especially young people, from the Estate. There have been holiday projects for young people and through lockdown online art clubs. Aylesbury might have been written off as a failed estate, but Harriet saw a rounded and warm community, admittedly with problems but nonetheless a community. As much as she taught people how to express themselves in art, she learned from them. And then one day, while walking past the Chiltern block during its demolition, Harriet had the idea of painting directly onto concrete fragments of Aylesbury Estate.

Technically, concrete is a poor surface to receive paint, and Harriet had to figure out how to prepare the surface. In her Aylesbury Fragments work what we see is re-purposed concrete waste from Aylesbury used to capture in meticulous detail the lives of a community that wasn’t supposed to exist.

Pigeon Netting, Wendover by Harriet Mean Hill

In an interview, Harriet explained why concrete?

‘As I travelled to work I became aware that the only activity continuing unabated was the demolition. Demolition is a violent, ruthless process.It affected me physically. In the midst of such uncertainty the destruction seemed to amplify the failure of the utopian ideals that guided the building of the estate. I reacted instinctively and started to retrieve pieces of shattered concrete that had escaped beyond the perimeter barriers.I didn’t have a conscious plan. The first fragment was a drawing of the skeletonised Chiltern as it had looked gutted awaiting demolition. I think ‘The Aylesbury Fragments’ began as an unconscious act of restoration in uncertain times, and speaks of something beyond the buildings themselves.’

Lights Out On, Aylesbury Estate by Harriet Mena Hill

Third Piece – The Architect

There is just one other piece of the story of Aylesbury. In her article, The Lost Architect of London’s Aylesbury Estate, Sarah Osei focuses on the enigmatic architect of Aylesbury Estate, Hans Peter “Felix” Trenton, who disappears from the public eye and the architectural record after the estate’s building. Many of the estate’s problems in design and construction are laid at the door of Trenton, much of that unfairly. he never publicly reacted to the opprobrium heaped on him. He was, in fact, an architect dedicated to helping those in society who most needed help. We now know that Aylesbury, ambitious in scale, was dogged by the familiar failings of local governments, insufficient money for maintenance and repair, and to solve the inevitable problems of new forms of construction.

Trenton was no stranger to marginalisation, to discrimination. He was born Hans Tischler in 1926, in Wroclaw, now in Poland but then a German city named Breslau. His father, the gifted artist Heinrich Tischler was arrested following the Kristallnacht pogrom when the Nazis attacked Jews and torched synagogues and Jewish properties across Germany while the police and fire service looked on or helped. Tischler was jammed into Buchenwald, the now notorious concentration camp, along with other artists, workers, pedlars, tailors, lawyers and doctors, all enemies of Germany because they were Jews. His health was broken by the brutal conditions, and he died soon after his release, aged 46. Heinrich’s wife, Else, with their two boys, Hans and his brother Franz, managed to escape to England.

In her article ‘Cursed art – post scriptum‘ Katarzyna Andersz writes in the magazine Chidusz further to the exhibition of Heinrich’s works in the City Museum of Wroclaw in the Royal Palace. ‘Cursed Art’ is devoted to Jewish artists active in the interwar period. ‘The central artist of the exhibition was the painter, drawing artist and architect Heinrich Tischler – a student of the architect Hans Poelzig and the painter Otto Müeller. Few of these artists’ work have survived, at least in the public domain (as we know anything of value was looted or expropriated by the Nazis and so may still be in private hands or hidden in a vault somewhere) but his family did manage to save Heinrich Tischler’s works.

Andersz writes; ‘Heinrich Tischler had two sons – Franz and Hans. Their names are straight from the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tale, the boys are pretty and very talented – as it turns out, they inherited their artistic talent from their father. In their last photo together, from October 1938, the three of them look happy. We don’t know when exactly it was made. Maybe there’s still over a month, maybe two weeks left until Kristallnacht, or maybe there’s no point in enumerating it, because anyway, they will soon lose their father…’

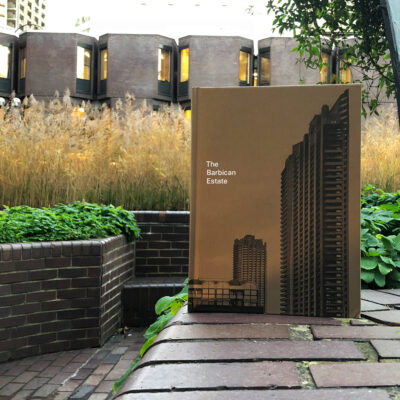

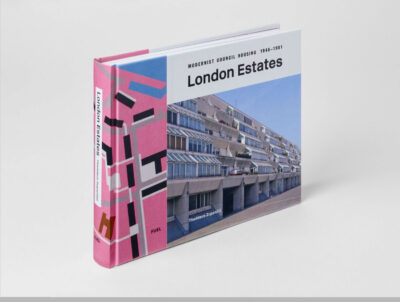

Hans anglicised his name; German names weren’t a smart idea as Britain went to war with Germany. Both boys grew up to be architects. Franz worked on the Festival of Britain while Hans Peter ‘Felix” Trenton became the Borough Architect of Southwark. Borough architects were hugely influential in the programmes of social housing construction from 1945 until 1981 that created hundreds of housing estates across Greater London (including some featured of the 275 featured in London Estates by Thaddeus Zupančič). Aylesbury was one of those needed projects. It sought to achieve so much and, in reality, was no failure. The blame must have been a heavy burden for a man, himself a refugee, who had lost so much, who worked so hard to improve lives for others.

In 1977 Hans began his own architectural practice but died ten years later at the age of just 61.

And that, in short, is the story of Aylesbury. There are no villains, but there are heroes, people who strove to make things better, who made a community and still do so, and who honour that community in art.