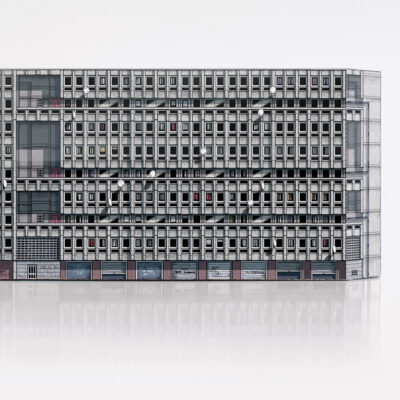

Robin Hood Gardens:

Taking From The Poor To Give To The Rich

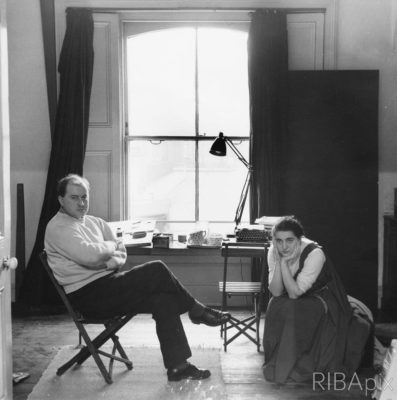

A close look at how the council is treating this brutalist icon. What the V&A has done in an unprecedented step to save an original piece of classical architecture by the Smithsons

We’ll be part of the ‘do you remember when they knocked down Robin Hood Gardens’ generation.

Located in the heart of Poplar, Robin Hood Gardens began life as a hope-filled project in the heart of London’s East East. Designed by Alison Smithson (1928-1993) and Peter Smithson (1923-2003) as social housing, created to help meet the acute need for homes after the devasting World War Two bombing, a situation exacerbated by a post-war baby boom.

The project was commissioned by the Greater London Council, the ‘GLC’. Robin Hood Gardens was completed by the Smithsons in 1972 at a cost of £1,845,585. One could argue that before it was even completed the seeds of its demise were sown.

Right to Buy

1972 was a big year for what was to be later the Right to Buy policy of the first Thatcher government. The scheme allowed local authority tenants to buy their homes. The sentiment behind the expression ‘an Englishman’s home is his castle’ runs deeper than one might at first imagine in the British psyche. Selling homes to tenants was not an entirely new idea, it had first been mooted by the Labour government in 1959. However, the scheme didn’t really get going for almost a decade.

Robin Hood Gardens began to welcome people to their new homes in 1972. Across England more than 45,000 tenants had decided to take up the Thatcher Government’s offer. Those who had previously rented for the first time had the opportunity to own their properties. There were various deals, for example, long-term tenants were offered a 20% discount on the market price for their homes. Whilst Right to Buy didn’t officially kick in until the following decade, in effect the scheme was well underway before.

Chronic Housing Shortage

The question we need to honestly ask ourselves now is, did Right to Buy contribute to a chronic housing shortage? Did that in turn ultimately lead to a real threat to estates like Robin Hood Gardens? Even more Machiavellian, did it just become too tempting for folks in a position of power to allow a misunderstood estate to fall into such a level of disrepair, that the argument for demolition would stick?

Many tried to step in and everyone failed. The Twentieth Century Society could not persuade the powers to be that listing mattered and that the estate must be protected. Richard Rogers described the estate’s ‘heroic scale’. One can only assume that the attention must have made developers salivate.

Alison and Peter thought big. The duo were heavily into changing the social status quo in a way that would meaningfully impact on how people lived. They were close to fellow members of IG, the Independent Group. This was a gathering of creatives which included artist Richard Hamilton, architect Colin St John Wilson and the art critic Rayner Banham, who wrote about New Brutalism.

This is Tomorrow

The group’s 1956 exhibitions Parallel of Art at the ICA and This is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel Gallery were recognised as groundbreaking. This is Tomorrow was created by 38 participants who formed into groups. Artist Richard Hamilton’s contribution was ‘Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing’. This iconic collage has since been recognised as a key early piece of pop art. This contributed to the feeling that change was coming and there was no turning back.

Another creative circle the Smithsons were part of was Group Six. Joining the Smithsons were Eduardo Paolozzi and Nigel Henderson. Regardless that Alison and Peter were in the middle of important artistic movements and were visionaries looking to improve living conditions for people in a disadvantaged neighbourhood ultimately stood for nothing. When the demolition ball swung in the direction of their biggest project sixty years later.

Blackwall Reach covers a piece of land which is bigger than the original Robin Hood Gardens. It will become home to 1500 people who find the idea of “high-yielding investment” appealing. The site will be composed, under plans at the time of writing, of 561 rented flats, 118 of which will be shared ownership. Another group of apartments have been marked for overseas private buyers.

We must constantly remind ourselves that Smithsons’ ideas were groundbreaking. Their story could have played out quite differently; they entered the competition to design Golden Lane Estate (think step one, with step two being the peachy prize of designing the Barbican, a brutalist estate that is properly appreciated and cared for). However, they lost out to Geoffry Powell, later of Chamberlin, Powell and Bon.

Corbusier

Losing out on that project did not hinder their flourishing architectural practice which they had started in 1950. From the off, they were never willing to compromise their vision and that brought them into direct conflict with Corbusier. Le Corbu, who, as we know, was not formally trained as an architect, was a key mover in the formation of the highly influential CIAM in 1928. CIAM, (Congres Internationaux d’Architecture moderne) in English, the International Congresses of Modern Architecture, ruled the roost in the immediate aftermath of WW2. There were a lot of building projects and opportunities.

1953 was a time of tangible change, it was clear that Europe’s political lines were being redrawn. Building materials became more expensive and some were harder to source. Newcomers on the scene Alison and Peter Smithson formed an alliance with Jacob Bakema, Aldo van Eyck, John Voelcker and Giancarlo De Carlo. They all found themselves at the July 1953 CIAM, its 9th Congress.

TEAM X

The Smithsons didn’t like what they saw at CIAM. They wanted to change the world and they felt CIAM was no longer the medium by which to do it. They became increasingly unhappy and frustrated, rejecting the setup and ideas. The Smithsons split from CIAM. Team X was formed. Alison Smithson’s 1964 book, ‘Team 10 Primer’ offers an invaluable insight into Team 10’s thinking. By 1955 Corbusier himself had left CIAM unhappy about the prevalence of English spoken at the meetings. By 1959 CIAM had disbanded.

Team 10’s first formal meeting took place in 1960. Evolution doesn’t always run smoothly. It was inevitable that differences of opinion would occur. The Smithsons became more and more committed to New Brutalism while Van Eyck and Bakema moved towards Structuralism.

Commissioned to build Robin Hood Gardens

With a canvas of 3.7 acres in the heart of Poplar near the London Docks must have been an incredible moment. The Smithsons spoke of creating ‘streets in the sky’. They planned a design involving two large long blocks, curved facing towards each other protecting a green area in the middle with its own man-made hill. The blocks were huge, dominant, composed of precast concrete slabs. One block was seven storeys high and the other seven.

What makes the estate’s demise all the more tragic is that the Smithson’s ideas were so clever and so carefully thought out. They had worked so hard in terms of improving the living experience for the residents in their individual homes and for the estate as a whole. Every element was up for re-imagining.

Bedrooms faced inwards and on every third floor, the Smithsons placed a wide balcony. Their intention was to encourage people to pass and mingle with each other and by creating a viewing balcony they hoped would create opportunities for interaction.

Pause Spaces

The Smithsons created ‘Pause Spaces’ by entrances and exits in and out of the estate with play areas for children. Alison and Peter were always considering ways of enhancing opportunities for human interaction. I like to think that they were really thinking about how to recreate the famed sense of east-end community among neighbours that existed in the former back-to-back housing or tenement blocks.

We now know that the dream estates, home to large numbers had major pitfalls which for some outweighed all their potential. Robin Hood managed to be, for some, a perfect home with a real sense of neighbourhood. For others, it was a place where for too many years criminal activity marred any pleasure derived from the design. The estate’s strange sense of geographic separation from other parts of the borough didn’t help. Fast traffic-choked roads w0und around it heading for the Blackwall Tunnel.

Blackwall Reach’s redevelopment scheme is part of the local 2012 regeneration project. The demolition of Robin Hood Gardens is part of that vision for the area. If the estate could be listed it could have been protected.

Demolition of Robin Hood Gardens

The demolition of the western block began in December 2017. The C20 Society wrote a bulletin in 2008 about the estate, this showed that the protests against demolition began years ago. It reminds us of Professor Stefan Muthesius’ view that

‘The Smithsons must be rated as Britain’s most important architectural designers and especially architectural thinkers, during the period 1950-1970. Their idea of community architecture was exceedingly influential throughout the world.

Robin Hood Gardens is the only proper concrete manifestation of their concepts and is thus of extreme importance, not only historically, but also for the present, as the concept of ‘design for the community’ still holds its fascination for architects and housing reformers.’

Today we have bulldozers, crumbling concrete and a lump of that once great example of a hopeful future protected and exhibited by the V&A

Image © Greyscape

Read Imperfect Beauty: photographing a city’s life-cycle

Cotton Street, Robin Hood Gardens ©Francisco Ibáñez Hantke