District 11 Budapest

Kelenföld

Reimagining a dormitory district

Bence Kapcsos has lived through the changes from a childhood home in a 10-storey panelház to seeing the gentrification of nearby neighbourhoods, less than 10 minutes from where he was born, to the news in September 2021 that a chunk of Kelenföld’s city centre has been sold to a private developer who has not yet revealed the final redevelopment plan.

For him, Kelenföld is the place where he grew up, where he spent his formative years, living in one of the typical Soviet-era modernist prefabricated panel housing developments, built to address a postwar housing crisis. We asked him what that was like and whether he felt that his neighbourhood was in need of ‘a new role in the 21st Century’ or might it simply evolve by virtue of its proximity to Ujbuda, the hipster paradise less than 10 minutes train ride away.

Fortepan/Kecskés András Kelenföld 1968 ©

How did satellite neighbourhoods like Kelenföld develop?

In socialist-era Budapest, mass public housing projects were typically (and luckily) built on the edges of the city. These areas barely had any infrastructure, everything had to be built from scratch. The first residents had a lot to contend with and very soon there were joined by another forty thousand residents.

The first generation of prefabricated housing estates had no provision for entertainment or community engagement, that’s how they came to be known as ‘sleeping neighbourhoods’ (alvóváros ‘sleeping city’ in Hungarian). By the time Kelenföldi lakótelep’s construction began, urban planners had learnt from the shortcomings of first-gen projects but there was a constant lack of funding. Estates often fell short of what architects had envisioned, though Kelenföld did achieve it’s architect Zilahy’s vision.

“The aim of the whole city centre is to attract people and create the cozy inner life of the housing estate,”

István Zilahy, Architect of housing estate in Kelenföld

Kelenföld Housing Estate

What’s it like now?

The answer depends on who you listen to and when they are referring to. Kelenföld has changed in public perception. It has gone from somewhere that people wanted to live, to somewhere criticised heavily in the press, and back to a place people are happy to call home.

Today it is surrounded by a middle-class aspirational neighbourhood. When it was in transition from post-soviet to where we are now there was a time when there were negative comments (unfairly) in the press. It is true many of the former socialist estates have problems reported by newspapers wanting to tell a particular story. One prominent article in 2006 called them, ‘soviet-type blocs in a disgraceful condition’ which was deeply unfair to the residents, especially if you bear in mind that these panelház are more than 40 years old and at that point people simply couldn’t afford to renovate their homes.

Fortepan / Erdei Katalin District 11 1969

What brought about the bad rep for panelháza?

This is not an issue that Budapest is solely dealing with. When they were constructed, the panel blocs were seen in a very positive light. Thinking in socialist terms it was all about improving the quality of living of the masses. However, their rushed and negligent construction, combined with the use of cheap materials resulted in a host of problems and irritations. Anyone who has had the experience of living in a ‘panel’ doesn’t forget it easily. But for all that my own memories are happy, I have a strong recollection of plenty of green spaces, sports facilities and everything within walking distance.

Kelenföld town centre

During the communist era, what were the criteria for being offered the opportunity to rent one of the homes in a panelház?

People could apply for apartments through the local housing council. The eligibility was decided on the basis of the applicant’s circumstances, occupation, class and background. The allocation policy prioritized applicants who were most in need of housing, young families with children but party members and people with “strong socialist commitment” (good cadres) got priority too. Personal connections were also important. A friend or a family member at the council could help a lot to get things moving.

Fortepan / Erdei Katalin District 11 1969

And what happened in the immediate aftermath of the fall of communism? Did tenants have the chance to buy their homes?

Yes, at a very favourable price, for a fraction of their market value. Very soon, over 80% of apartments in pre-fabricated blocs were in private ownership.

Kelenföld Tram Depot CC BY SA 4.0 Image Kemenymate

How did that work out?

It didn’t take long before people wanted to distance themselves from a failed state and those who could afford to began to move on and move out to newer homes or to the suburbs. In the eyes of many, the run-down, grey blocs were seen as relics of socialism. However, people without the economic means had nowhere to go, they got stuck.

Fortepan/Szalay Zoltán 1970

Are there still a lot of first-generation residents?

Not so many, a lot of the new homeowners are next-gen, people who bought their apartments from original residents who had moved into the estate in the 1960s -1970s. This group seem better off and their presence is transforming the area.

And for those that could get away?

They became part of the next phase in the country’s move away from socialism and have driven the real estate boom. What is interesting is that whilst lots of people wanted to get out, once they did, they really began to appreciate some aspects of the socialist housing they’d left behind. They could see the advantages and benefits of living in a planned environment for large numbers of people. For example, the location and number of facilities – schools, kindergarten, shops, recreational areas and parking. The way the public transport system was designed to serve the needs of the community, the green spaces.

Image Bence Kapcsos

Where are we now?

There’s been an interesting development, the addition of a new metro line giving fast access to central Budapest, a new shopping mall and entertainment complex, actually the third largest in Hungary is currently under construction. It’s clear that modernization and investments has brought an improved quality of living to the residents of Kelenföld. However,

‘when new arises from the old, some sort of loss is inevitable’.

The local underfunded Community Cultural Centre lives under the threat of impending demolition. Their facilities serving the needs of elder members of the community are tired and neglected structurally but the community has a lot of character and a lot of heart. The interior has a strong ’90s vibe. The former cinema hall has been modernized, and hosts theatre plays and conferences. A trendy café with an exhibition room has opened on the ground floor.

Fortepa Bojár Sándor District 11 1974

Bartók Béla Boulevard in Ujbuda is fast becoming a hipster paradise, do you think the impact of its proximity to the neighbourhood will change perception and lifestyle in Kelenföld?

I think it’s great that District 11 (kerület 11 in Hungarian) has now become such a cool, vibrant neighbourhood. However, that is not the main driving force behind the transformation which the district as a whole is experiencing. Thanks to its sheer size the district is very diverse in terms of architecture and history. You can find beautiful pre-war neighbourhoods around Bartók Béla boulevard, cheek by jowl with housing estates like Kelenföld and former industrial areas that are now being recultivated. Take, for example, Budapest’s biggest real estate investment project BudaPart, it’s happening here in District 11.

BudaPart under construction

Image Bence Kapcsos

How will the changes impact the people living in Kelenföld?

Without a doubt, Bartók Béla Boulevard’s new coolness is adding something to the mix and desirability of certain areas. It is also adding to the pressure for change which some people are not ready for. So, yes it will impact Kelenföld but perhaps it’s too early to tell to what degree and to whose benefit.

Fortespan Kecskés András 1975

Greyscape Quickfire Questions:

Best Hungarian dish we must all try? Bajai halászlé (Fishermen’s soup “Baja” style)

Best bar in District 11? Béla (on Bartók Béla boulevard)

Best place to try a thermal bath? Rudas thermal bath

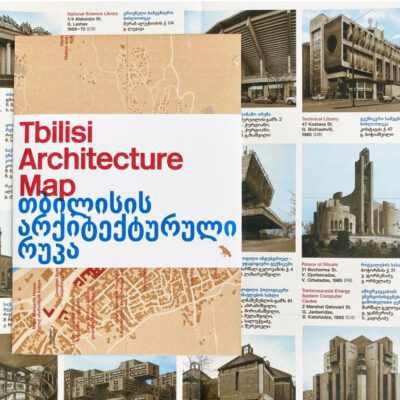

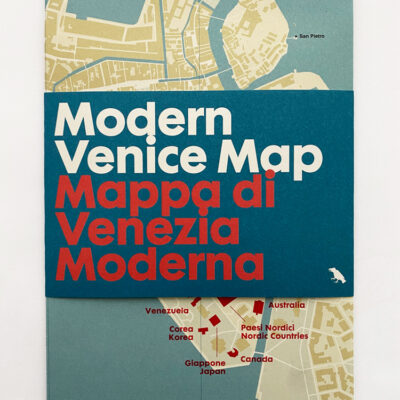

Kelenföld found itself in salubrious surroundings in 2021. After several false starts, the 17th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia finally opened, and the Hungarian Pavillion is featuring Kelenföld’s vast socialist-era housing estate (and another 11 hot spots) for Othernity, reconditioning our modern heritage.

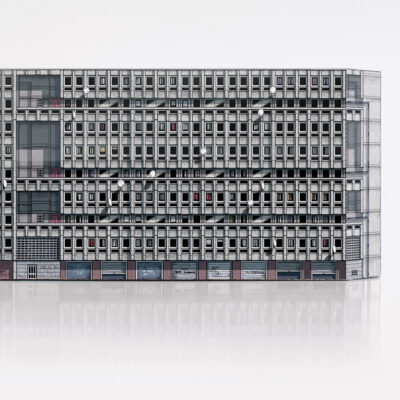

Kelenföld featured in the Othernity, Hungarian Pavillion’s ‘Othernity’ at the 2021 Venice Biennale

Kelenföld City Centre: Architect István Zilahy and József Bada

About Bence Kapcsos:

A UX designer and self confest prefab panel bloc enthusiast based in Budapest.

Find Bence on Instagram www.instagram.com/panelgrau/

On his website

All images unless otherwise stated, the Copyright of Bence Kapcsos

Panoramic view of Kelenföld taken by Bence from his parent’s apartment