Chernobyl

The irradiated heart of the nuclear power plant is, again, an open wound

We might have thought Chernobyl a dangerous relic, a lesson about the arrogance of the USSR attempting to control the most fundamental and dangerous forces in nature. But here we are in March 2022 with the invading Russians having shelled Chernobyl and other nuclear sites in Ukraine; a mad Russian Roulette to prove Putin can’t be tamed, will take wild risks with the lives of millions. Chernobyl is not a radioactive wasteland going through a rewilding, anymore.

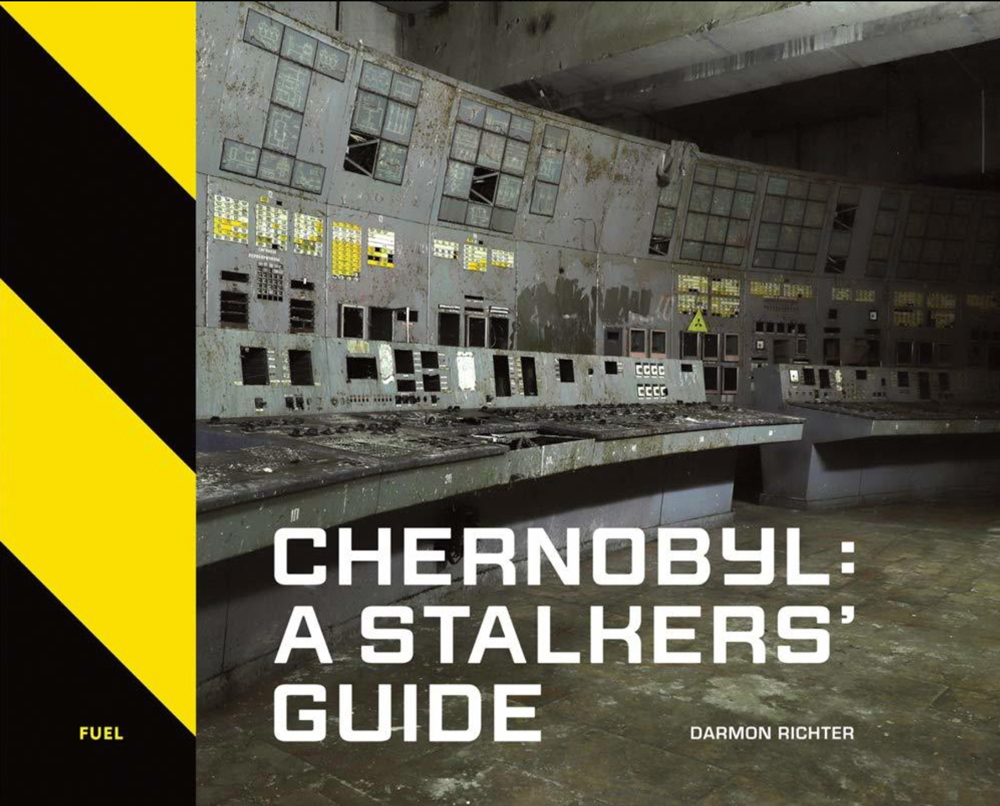

Pripyat is seared into our collective memory as the home city of Reactor No 4 of the Vladimir Illyich Lenin Nuclear Power Plant. The 1000 sq ml area, the now ironic Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, has been until everything changed so dramatically the epicentre of a “secretive ‘stalker’ subculture. Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the zone was one of the most visited tourist destinations in Ukraine, in places dressed like a movie set of dystopian ruin to provide photo ops for curious visitors. British writer, guide, urbex-hunter and photographer Darmon Richter’s 2020 book, Chernobyl: A Stalkers’ Guide, took the reader into the site, not just the darkness and the horror and the sacrifice of lives courage that saved us from a far worse disaster, but the remains of a Soviet ‘atomgrad’, atomic city. How much of abandoned Pripyat has been further destroyed is unknown. Darmon now isn’t focused on writing but on extending help to his friends in Ukraine.

The book gives voice to people who were there in the early hours of April 26th 1986 when a routine safety test went catastrophically wrong, and to those who came later from scientists and policemen to the people who had to leave their homes in Pripyat never returning.

We’ve revisited our 2020 interview with Darmon, to see what Chernobyl then, the disaster that led to its evacuation, might say about the new tragedy for Chernobyl.

The first time he went to Chernobyl, Darmon came home with a memory card full of shots of beautiful, melancholy decay: crumbling furniture covered in ivy, children’s toys in abandoned nurseries and decaying books. But it isn’t authentic. Many of those scenes were staged by other post-disaster visitors or sometimes by the tour companies themselves, who profited from this sensationalism more than anyone else.

Over the course of his many visits Darmon became far more interested in the concrete heritage of the place – both figuratively and literally. Pripyat had been an unusual city. It was established as an ‘atomgrad,’ the name given to cities involved in the USSR’s nuclear programme. But while the other Soviet atomgrads had changed and evolved over time, often being adapted for new industries, and a different style of living, Pripyat was frozen in time. Pripyat’s streets were meant to be the model of a Soviet utopia.

So Darmon’s photographs focus more on the design of Pripyat, its streets and buildings; on the synthesis of new and old technology at the power plant; and also on the monuments that were raised to commemorate war heroes in all the villages of the Chernobyl region. He created images that de-sensationalised the Chernobyl Zone, de-mystified it, and instead offered an honest record of its shapes, forms and colours. of course it was impossible to ignore the decay of the buildings and the streets. Now, marked by Russia’s war against a fellow Slav nation, Pripyat speaks eloquently of how far from the ideals and lofty ambitions of the Soviet Revolution Russia has fallen.

Tourism and HBO

Darmon first visited in 2013 as part of a Russian-language package tour, returning more than 20 times since watching the evolution from the site of the world’s worst nuclear disaster to a dark tourism destination.

Visitors have got to Chernobyl by one means or other since the early 2000s, but the real tourism boom started sometime around 2015. That year saw a 90% increase in visitor numbers compared to the year before… the next year, it went up by 125%. In 2019, the year the HBO miniseries about Chernobyl aired, there was a 72% visitor growth. Chernobyl seemed to be a piece of history, to be visited, to be photographed for holiday snaps, to be printed on caps and shirts.

‘Tour guides always had to carry a dosimeter, but recently each individual tourist had a radiation meter to hang around their neck… while the guides had to carry a GPS tracker too, just to make sure they were not taking tourists anywhere they were not supposed to!’

Chernobyl became the highest-grossing tourist attraction in Ukraine.

Is the site decontaminated?

‘An incredible amount of decontamination work has already been done at Chernobyl’, Darmon notes, ‘However, there are still a number of ‘hotspots’ around, which are often caused by the presence of tiny particles of fuel, or debris leftover from the disaster. Pripyat Hospital still contains the bandages used while treating firemen and other first responders at the power plant, and these materials are still heavily contaminated’.

It is unlikely that all of these waste particles will ever be found and contained, and it’ll take thousands of years for all of them to naturally decay to safe radiation levels. The Russian army’s trucks and heavy equipment roiled the surface and the radiation spike recorded after the Russian army’s advance into the Zone was, it is thought, caused by all those particles being disturbed.

After the disaster back in 1986, a concrete and steel sarcophagus was assembled over the destroyed Reactor 4 to contain the worst of the radiation. It was designed to have a safe lifespan of around 30 years, which has now expired. In 2016 a new structure called the ‘New Safe Confinement was installed over the top of it. The plan was to crack open the old sarcophagus within and begin dismantling the contents. That wreckage is believed to contain hundreds of tons of uranium fuel, much of it now melted and mixed with other materials. It all needs to be separated and sorted using remote-controlled cranes, before sealing it inside secure containers that can then be taken out of the structure, and transported to nuclear waste storage facilities elsewhere.

The New Safe Confinement is one of the most fascinating structures – and Darmon was lucky enough to be taken inside and given an exclusive tour of the secure area under the arch. The New Safe Confinement was designed for a hundred-year lifespan.

Although Reactor 4 had been destroyed the three remaining reactors continued to generate power until the last was turned off in 2000. Their radioactive fuel is stored in cooling ponds that are now without their diesel-powered cooling systems. Experts believe that the fuel is sufficiently degraded not to be radioactive enough to boil away the cooling water and that their building will contain the danger. There will be no plume of radioactive fallout carried on the wind, at least from Chernobyl.

What now

Darmon has been working on other projects but right now his only focus is helping his friends in Ukraine. We look forward to peace when he can resume those projects. In the meantime, enjoy his photographs.

All images the Copyright of Darmon Richter

Follow Darmon Richter on Instagram at www.instagram.com/ex.utopia

Darmon recommends visiting https://how-to-help-ukraine-now.super.site