A Modernist’s Vision, Ernst May

Frankfurt’s housing crisis of the 1920s was as critical as it is in today’s major cities: We need a visionaries like Ernst May and Ludwig Landmann for the 21st century?

Ernst May’s architecture was shaped by his determination to solve what remains, a century later, a ubiquitous problem: creating affordable, decent housing in a well-planned environment suitable for working-class people. A place with light, air and sun, Licht, Luft und Sonne.

A look at his life sheds light on his quest and whether the price that was paid to achieve his modest but utopian dream was too high for some of the residents.

Born in Frankfurt in 1886, the son of a leather manufacturer, Ernst May studied architecture in Darmstadt and Munich, with a term at University College London in 1907. At TU Munich, he came under the influence of Theodor Fischer, the joint founder and first chairman of the Deutscher Werkbund and an early city planner.

This was a time when the notion of the Garden City was coming to prominence. Ernst May returned to London in 1911 to take up an apprenticeship with Sir Raymond Unwin, a key figure in the British Garden City and Arts and Crafts Movement. May would later apply what he learned to the Hellarau project in Dresden, Germany’s first Garden City and in the ZigZag Housing project (Zickzackhausen), an important example of the New Building Movement. These projects attracted significant attention in architecture and design circles.

The First World War stopped everything. May served on the Eastern Front. He returned to his hometown of Frankfurt and quickly formed important connections with modernist architects and designers such as Erich Mendelsohn, Hugo Häring, and J.J.J. Oud. His move to Breslau (now Wroclaw) was entirely logical, the city was a magnet for modernists. Ernst May was invited to become the Technical Director of the non-profit settlement company, Schlesische Heimstätte, (the Silesian Land Company). Herbert Boehm undertook his technical placement with May in Breslau, and together, they played a significant role in the development of the settlement.

Meanwhile, Frankfurt, May’s home city, was undergoing enormous change. In 1924, the city elected a progressive new mayor, Ludwig Landmann. One of his first actions was to bring in May and appoint him City Councillor and Head of Urban Development, a role he would remain in until 1930. Landmann and May formed a close relationship. Landmann died of malnutrition in hiding from the Nazis during the 1945 Hunger Winter in the Netherlands.

May and Landmann shared a vision to deliver the Neues Frankfurt (New Frankfurt) initiative. May’s beliefs were underpinned by the idea of ‘wohnkultur’, the notion that architecture had the potential to create social change. A building block to achieve this was the creation of the Nassauische Heimstätte, a housing and development company, to oversee construction projects, with May sitting on the supervisory board.

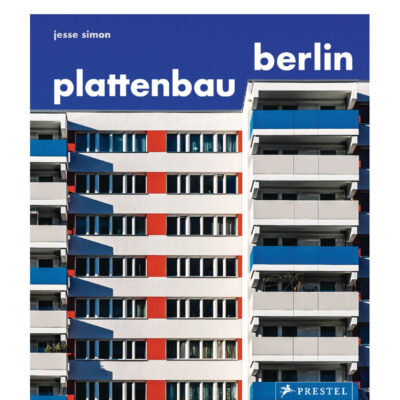

The overarching aim was to develop Frankfurt’s modern, large-scale public housing programme and provide every citizen of Frankfurt with access to affordable housing with enough light and space. For the project, May gathered around him a forward-thinking team of architects. To give a sense of the scale of the problem, by the interwar years, more than two-thirds of Germans were living in overcrowded urban areas or without a home. Overcrowding had all sorts of knock-on problems.

Twenty-four settlements were created, satellite neighbourhoods informed by the Garden City movement, all with the aim of encouraging a new way of living and interaction with neighbours. The project was considered a huge success. It caught the attention of the international architectural world.

But, it was not plain sailing. Criticism was levelled at May’s socilism, that his politics affected the designs too much. Take Siedlung Römerstadt, one of the developments, as an example; everyone had electricity, the homes were not large but they were sufficient. Each had a New Frankfurt kitchen. As the prices of power spiked, the residents simply couldn’t afford to switch on the electricity and wanted to return to burning coal – in homes not designed to accommodate coal use, which, according to reports, left them sitting in dark, cold rooms without working cookers or water heaters.

Constantly looking for ways to promote modernism, Ernst May joined the Deusche Werkbund in 1925 and Der Ring in 1926, the important circle created to increase understanding of Modernist Architecture and the Neuer Bauen, the new building movement. He also travelled as part of an international delegation to participate in the International Conference of City Planning in NYC, where he met many of the American leading lights, including Frank Lloyd Wright and Lewis Mumford. In 1927, he contributed to the Weißenhof project in Stuttgart. The following year CIAM, the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne, was founded in Switzerland. Ernst May became a founding member and a year later he hosted the second gathering in Frankfurt.

Licht, Luft und Sonne

The enlightened thinking only went so far. The team was all-male until Ernst May invited the first female to graduate from the Bauhaus, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, to join his team. One of her best-known designs is the New Frankfurt kitchen, the forerunner of today’s fitted kitchen.

Meanwhile, the Soviet government was grappling with a similar housing issues, huge numbers had moved from the country to the cities and homes were desperately needed. In 1930 May was invited to lecture in Moscow, Leningrad and Kharkov, which led to him being offered a three-year project as Chief Engineer of Urban and Settlement Construction of the USSR. May gathered his twenty-strong ‘May Brigade’, including luminaries such as Arthur Korn, Fred Forbat, Jan Rutgers, and Matt Stam. Their brief was to plan twenty new cities. But, when they arrived, it was immediately clear that the situation on the ground was far more complex.

Their first stop was in Magnitogorsk, which they were credited with building over a three-year period. Records show that, like much at that time in the Soviet Union – progress was slowed by bureaucracy and corruption. The three-year contract ended in 1933 when Hitler came to power. Nazi Propaganda minister Goebbels, negatively name-checked May in a radio broadcast and it was clear May didn’t dare return to Germany. Instead he heads to British East Africa, to today’s Kenya. Others in the brigade returned to their home countries or became refugees. May’s designs in the Soviet Union fell out of favour very fast and the Soviet government changed policy, non-Russians were no longer invited to undertake projects.

Life was very different for May in exile in Africa; stateless, he was interned by the British as an Enemy Alien in 1940. In 1942 he was, again, interned this time in South Africa. For a time, he became a farmer in Tanzania before eventually being able to return to his real love, architecture working from an office in Nairobi. May designed schools, hotels and commercial buildings, some standalone and some with Vienesse-born architect and town planner Erica Mann, who later made a significant contribution to the 1948 master plan for Nairobi. May’s first project after 1945 was to create his family a home.

May eventually returned to Germany in 1953. He led the post-war planning of the severely bombed port city of Hamburg. He is credited with creating the New Altona district of the city.

He returned to his school TU Darmstad as an honorary professor in 1957 writing about urban planning.

He died in Hamburg in 1970 leaving behind him an incredible legacy.

Credits: https://ernst-may-gesellschaft.de/home.html

Image of the Zig Zag Houses, Zickzackhausen by Christos Vittoratos CC BY SA 3.0