VIENNA:

BAROQUE AND BRUTALISM

Join us on a dive into brutalist Vienna, a city well known for that other Italian import, the Baroque, with Australian landscape architect Duncan Gibbs. His tour de force traces the echoes in the designs from the earlier to the later movement. We also discover what a ‘gesamptkunstwerk’ is and its impact on local architecture.

Viennese Modernism finds its first manifestations and intellectual roots in Austrian architect and urban planner Otto Wagner’s late 19th Century Vienna. He invented his own capitals to columns, shaking the entablatures down the whole façades of his buildings. Adolf Loos famously condemned the criminality of ornament so leading Emperor Franz Joseph to avoid Michaelerplatz so that he didn’t have to be confronted by that house with “no eyebrows.” The creative energy of the Wiener Werkstätte, experimenting in crafted mass production, Thonet’s pioneering furniture designs, both coincided with the rise of Red Vienna following the end of WWl and its dramatic residential projects to tackle a housing crisis.

Well after the ruinous events of the Great Depression and WWII, Modernism returned but altered by its journey back home. Brutalism with its raw quality had a particular Viennese vibe.

Konzilsgedachtniskirche Lainz Speising

The ultimate in Viennese brutalist architecture for Duncan is the Konzilsgedächtniskirche Lainz Speising (Council Memorial Church Lainz Speising) completed by Josef Lackner in 1968 in Hietzing.

‘It’s a supreme use of concrete in different forms, considering the order of works involved to achieve the combination of textures. High-density smooth concrete in blocky details liberally spread through the building counterpointed with big panels of ‘Leca concrete’ that used expanded clay balls as aggregate to create the distinctive texture’.

Konzilsgedachtniskirche Lainz Speising

‘Then there is the crisp white steelwork of the pews and roof, as well as the calming sound created by the beige carpet. The Leca concrete also helps muffle the vestigial echo of the interior, assisting in the creation of a warm contemplative embrace. The corner openings are a lovely touch and introduce a diagonal experience of a square space. The Casson Conder Partnership imitated them on the Ismaili Centre in South Kensington, London 24 years later.’

Konzilsgedachtniskirche Lainz Speising

Lackner’s other brutalist church, the Glanzinger Pfarrkirche, north-west of the city, Duncan shares ‘is similar to the Konzilsgedächtniskirche, this church is designed as a ‘gesamptkunstwerk’, or ‘total-work-of-art’ where the architect designed almost everything or had some degree of control over all aspects. Although this artistic concept is often said to originate with Richard Wagner’s operas, or architecturally to Frank Lloyd Wright, Duncan argues that its originals are firmly found in the Baroque.

‘An interesting example that very much sits within the tradition of Vienna is the Pfarre am Schöpfwerk Kirche and estate built in 1974 and designed by Victor Hufnagl. The forms are most definitely in the brutalist tradition, but the decorative references go back to the gridded studs of Wagner and the Österreichische Postparkasse, and the gridded latticework of Hoffman.

Pfarre am Schöpfwerk Kirche

Whilst the estate buildings themselves are fairly straightforward in their form and organizing thought, the church itself stands out with what I can only think of as being a kind of brutalist version of the Victorian style of ‘Blood and Bandages’ architecture with white concrete framing panels of red brick, whilst the interior has a distinctive Secessionist feeling. Apparently, the estate hasn’t been the greatest success, with a significant turnover of residents, but sometimes the management of buildings can make the best architecture unlivable, which I suspect might be the case here.’

The real treat is Duncan’s bucket list of must-see Viennese brutalism.

Wohnpark Alterlaa

‘The six soaring towers are a brutalist marvel unmatched anywhere else. Parks undulate around the towers’ bases and climb up the sweeping sides in the form of balcony gardens. Designed by Harry Glück and Franz Requat and built between 1968 and 1973, this place feels like one has stepped into the future; the kind of sparkling and optimistic future that seems so remote in this day and age. This estate is hugely successful with a strong retention rate of residents, ample recreation facilities perched at the top of each tower and shopping in a network of pedestrian streets and squares, whilst all the traffic and parking is kept below ground. I can only describe this as a work of inspired genius, but one that nearly didn’t happen due to the controversial height of the towers in what is a reasonably low-rise city.’

Pfarrkirche Liesing

A lovely surprise was the Pfarrkirche Liesing by Josef Pillhofer built in 1955 on the site of an older church; one of several that had marked this site as a place of worship since 1432. It’s a delightful combination of strongly brutalist forms with elements of the International Style, and references to the Medieval dotted throughout.

Pfarrkirche Liesing

Wotruba Church, the Kirche Zur Heiligsten Dreifaltigkeit

A trip to Vienna wouldn’t be complete without visiting the ultra-brutalist Kirche Zur Heiligsten Dreifaltigkeit, more commonly known as the Wotruba Church, designed by Fritz Gerhard Meyer after a model made by the famed Austrian sculptor, Fritz Wotruba, and built from 1974-76.

Its complex geometries of intersecting concrete blocks create the unique external appearance whilst defining an exhilarating set of volumes that expand and compress the experience as you move through, with the highlight being passing from the main space into the smaller chapel off to the side.

I know some architects aren’t a fan of this arguing that sculptors can’t design buildings but I for one am glad it’s there, even if as an experiment in form, volume and materials. In it, we see the transformation of a style of playful modernism into next brand of Austrian architecture; that of deconstructivism. This kind of transformation apes the move from the high Baroque into the darker and more experimental forms of the Mannerists, both in painting and architecture.

Oberbaumgarten church

About three kilometres north of Lackner’s Konzilsgedächtniskirche, is the Oberbaumgarten church by Johann Georg Gsteu from 1965, only a few years prior to Lackner’s work. The structure was inspired, like the Baroque, by the ideals of ancient Rome, in this case, the Pantheon, where the use of coffered concrete is here imitated by waffled structural concrete on full display in the ceiling in spectacular fashion.

The square cross leitmotif repeated throughout forming the basis of the form of the building, the four quarters bridged only by glass from the doors up the walls and across the ceiling to the centre. This is a kind of reference to the traditional nave and transept where the commoners alter is located at the crossing, whilst doing away with the apse completely, further playing on this language of architectural typology that typified the kind of experimentation of Wagner, Loos and others seventy years earlier.

Pfarre Kirche St Florian in Margareten

Well worth the 15 minute brisk walk from Innere Stadt is the youth-based church of Pfarre Kirche St Florian in Margareten. It is just south of the city centre. Designed by Rudolf Schwarz it was faithfully completed by Johahn Petermaier from 1961-62 after Schwarz’s death. Like Oberbaumgarten, a similarly structurally daring building with diagonal and vertical concrete ribs filled in with stained glass by Giselbert Hoke. However, I feel it is more of a brutalist take on the gothic style with coloured light flooding in from the sides. I’m not sure who carved the ‘stations’ reliefs but they’re quite superb.

Stained Glass Window and Organ Pfarre Kirche St Florian

21er House aka Belvedere 21

21er House, now called Belvedere 21, was by the great Karl Schwanzer. This was first designed in 1954 as the Austrian Pavillion for the 1958 Brussels World Fair. Later relocated back to Vienna as the first dedicated modern art museum for the city. Whilst it’s a steel and glass construction, I argue it’s a brutalist building because it’s such an expressed structure where everything is on show. Designed to the modest budget post-war Austria could afford, it was reconstructed and reopened on its current site in 1962. It underwent a substantial renovation from mid-2008 that was completed in 2011.

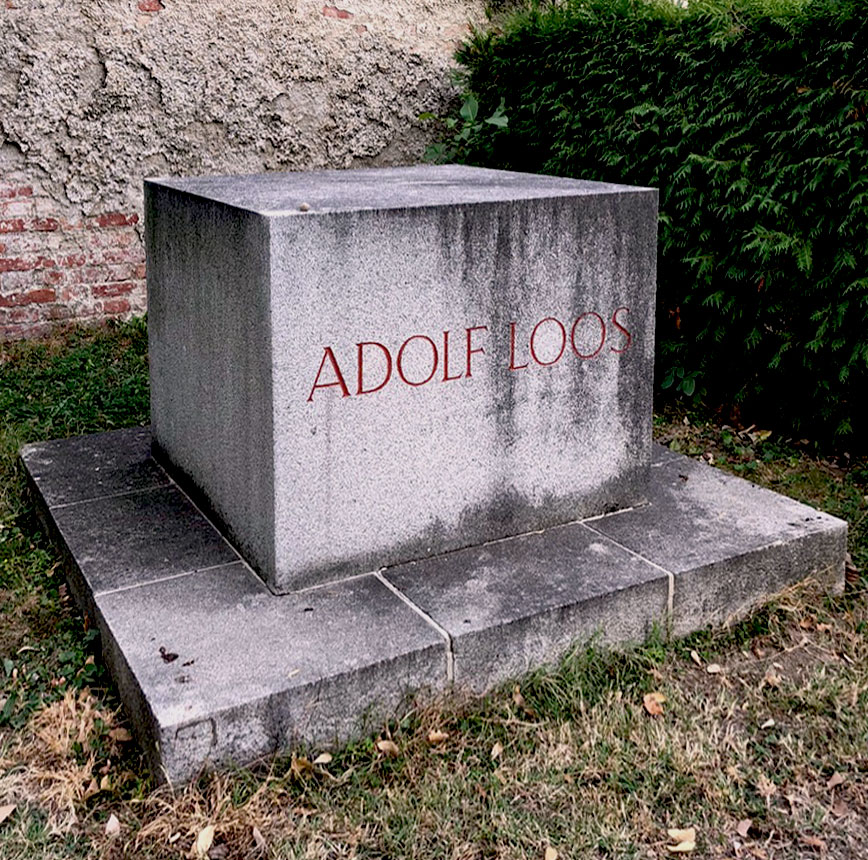

Zentralfriedhof

It seems somehow appropriate to finish in Vienna’s fabulous necropolis of the Zentralfriedhof. Here, (and mostly in the very centre of the cemetery) you’ll find a cross-section of Viennese architectural history, with the simple block gravestone Loos designed for himself (that’s out along the boundary wall), but also Wotruba’s headstone for the composer Arnold Schönberg (1974), as well as (likely) Gerhard Mayr’s headstone for Wotruba himself (1975).

Gravestone of Fritz Wotruba

A rather wonderful headstone, designer unknown. It was created for the architect of the Frankfurt Kitchen, Margarette Schütte-Lihotzky along with the neoclassical and monumental headstone for Franz Schubert by Theophil Hansen. It was Hansen who was the architect responsible for nurturing the talents of Otto Wager. But perhaps it is the last work of brutalism in Vienna, and not too old either: The 2012 single block of laser cut and laser engraved (internally!) glass, that forms the headstone for the seminal Hungarian composer György Ligeti designed and built by the emigre architects Aneta Bulant from Bulgaria and Klaus Wailzer from Berlin. This simple combination of concrete and glass with Ligeti’s name hanging magically in space inside the glass block is superb but easily missed in the cornucopia of grave architecture that is represented there.

To some degree, this last piece also encapsulates the spirit of brutalism in Vienna. Imported and remade with the language of architecture being played with and on full display. It also plays with the more contemporary practice of deconstructivism. I argue that this is the grandchild of Viennese modernism, born from that prodigal child of brutalism. It traces its way back to the post-war period. In its variety of forms and treatments, it outshone how the style was treated outside Austria. Where, perhaps, more doctrinaire approaches to that raw architecture were taken.

‘Vienna remade brutalism and sent it off, out into the world as another new form for the rest of us to grapple with.’

It is like the city’s long journey from the Baroque palaces of the Innere Stadt to the new techniques and inventive central organising ideas of Wagner and the stripped back forms of Adolf Loos that were an original architectural revolution of the early 20th Century. We just need to notice what was done here since then.

Duncan’s bucket list for his next visit.

Glaubenskirche in Simmering

CC BY SA 3.0

Further south is the only protestant church in Vienna I know of built in the brutalist style. The Glaubenskirche in Simmering is where the materiality and simplicity are supposed to echo the protestant rejection of catholic embellishment. Designed by Roland Rainer in 1954, the church was built from 1962-63. This was the one other brutalist site on my list I missed out on aside from Lackner’s Glanzinger Pfarrkirche to the north of the city.

All images Copyright of Duncan Gibbs ©

Follow Duncan Gibbs on Instagram www.instagram.com/duncan.gibbs/

Learn about Duncan’s Landscape Architecture practice http://www.duncangibbs.com.au/