The Values of The Brutalist

Concrete giants: European Legacy in a New Land

Barbican Rooftops Image Greyscape ©

Brutalism, Modernist Architects, and the Jewish Influence on Modernist Design

The movie The Brutalist has triggered fresh interest in the origins and development of modernist architecture. The film is wrapped in the bold, austere aesthetic of Brutalism. Played by Adrian Brody, the principal protagonist is a gifted modernist architect, a Jew, a survivor of the Holocaust and an immigrant, a stranger in a strange land. Architects of Jewish heritage made significant contributions to modernist design and we ask the question, why?

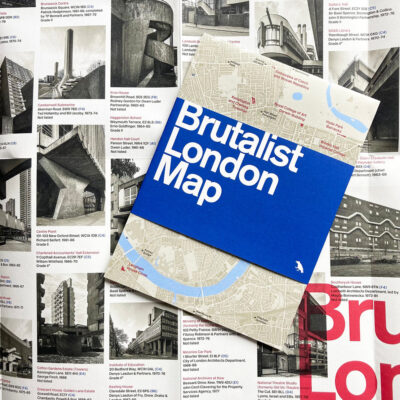

The term “Brutalism” itself is derived from the French word “béton brut,” which translates to “raw concrete.” It was popularized by the British architectural critic Reyner Banham in reference to the work of Le Corbusier and his use of stark, unadorned concrete surfaces.

A Movement Born of Upheaval

Modernism, and its offspring Brutalism, emerged in the early 20th century, an era marked by dramatic societal, political, and technological transformations. For Jewish architects and designers, the movement represented an opportunity to break from tradition and an establishment that didn’t want Jews joining the profession. Modernism rejected the historicist and ornamental styles of the 19th century, favouring rationality, abstraction, and functionalism. To those who had survived the Great War there was a desire to embrace the new, to use materials and technology in a new aesthetic and one, significantly, that could improve the living conditions of not just the rich but the working classes, too.

Jewish thinkers and architects gravitated toward this philosophy for various reasons. Many saw modernism as a way to challenge entrenched norms and redefine their place in societies where they often faced marginalization. The egalitarian ethos of modernism resonated with Jewish values that emphasized intellectual exploration and social justice. Visionaries such as Marcel Breuer, Erich Mendelsohn, and Richard Neutra were instrumental in shaping modernism, drawing from these principles while pushing the boundaries of architecture and design. The modernists published hundreds of manifestos and papers, envisioning their design ethos as but one part of a road to social improvement and for some socialism. Immediately in the wake of the October Revolution in Russia there was a great flowering of radical new design. Russia was the crucible that produced its own modernism in Constructivism until the iron grip of Stalin’s tyranny crushed the movement and purged the artists and designers who had with such heartfelt devotion fallen for Bolshevism.

Image Howard Morris

The Role of the Diaspora

The rise of fascism in the 1930s forced many Jewish architects to flee, leading to a diaspora that would spread modernist ideals globally. With anti-Semitic regimes targeting Jewish professionals and artists, Germany, Austria, Hungary and Poland became inhospitable for Jewish architects while doors to Jewish immigration were closed in many more countries. First, they were expelled from their professions losing their livelihoods, their work condemned as degenerate and later, unless they could get away, they would lose their lives.

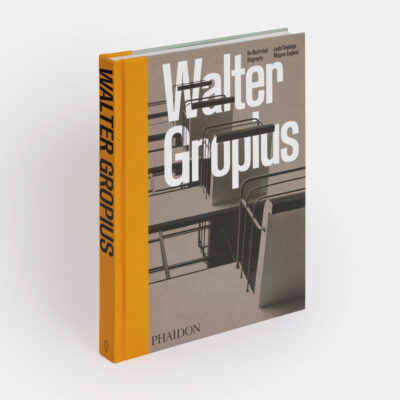

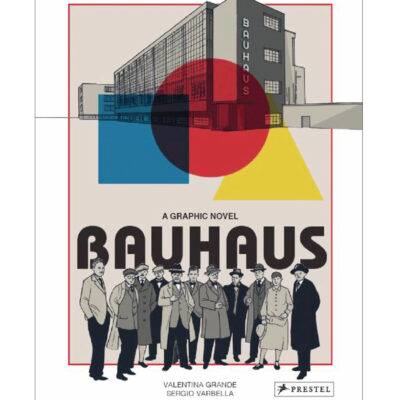

This exodus, while tragic, allowed modernism to take root far beyond its European origins. In the United States, Jewish émigrés like Marcel Breuer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (a modernist leader who collaborated with Jewish colleagues at the Bauhaus) played central roles in integrating modernist design into the American architectural landscape. The Bauhaus, with its experimental approach to unifying art, design, and technology, became a foundation for the work of many Jewish architects and designers as they adapted its principles to new cultural and economic contexts.

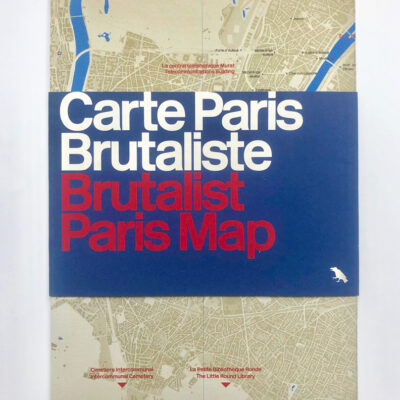

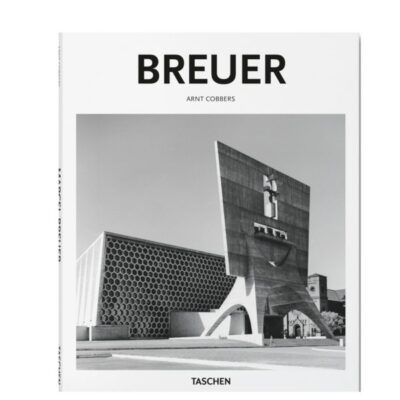

Marcel Breuer is renowned for translating the minimalism and functionalism of Bauhaus design into striking architectural projects and furniture pieces. His Wassily Chair, constructed of tubular steel and leather, epitomized modernist ideals of efficiency and elegance. In the post-war era, his work evolved further, influencing Brutalist architecture, with buildings such as the UNESCO headquarters in Paris and New York’s Whitney Museum reflecting the movement’s emphasis on monumentality and raw materiality.

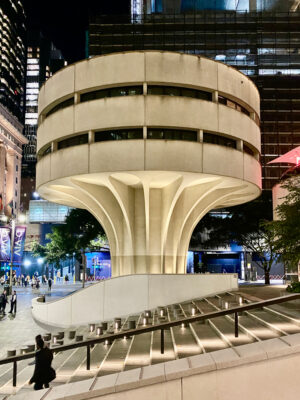

St Martins Place, Harry Seidler, Sydney Image Mike Oliver

Brutalism and Resilience

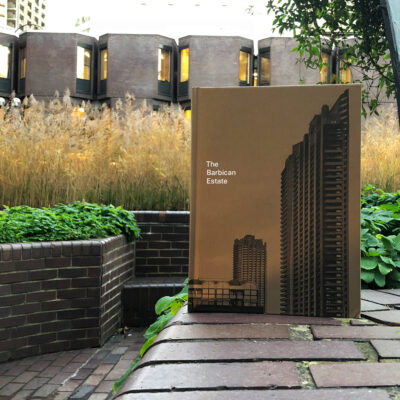

Brutalism, emerging in the post-World War II period, became a material response to the challenges of rebuilding societies and addressing urban housing shortages. Its defining characteristics—monumental concrete structures, bold geometric forms, and a focus on functionality—aligned with the modernist ethos but carried an additional layer of meaning for Jewish architects who had experienced displacement, war, and cultural upheaval. There was a need to create decent homes for working people who had lived in squalor and deprivation and to do so quickly. But there was a naivety and sometimes a meanness in the commissioning authorities that great concrete residential estates would not need maintenance. So whilew the Barbican has flourished, Aylesbury Estate and Pruett-Igoe were neglected.

For architects like Ernő Goldfinger, Moshe Safdie, and Marcel Breuer, Brutalism was not only an aesthetic but also a moral project. Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower in London, for example, exemplified the Brutalist commitment to creating accessible housing while incorporating communal spaces that encouraged interaction among residents. Though controversial at the time, Trellick Tower is now celebrated for its visionary design and enduring presence in London’s urban fabric.

Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67, created for the 1967 World Expo in Montreal, takes Brutalism in a different direction. By combining prefabricated concrete modules into a highly adaptable housing complex, Safdie addressed issues of density and quality of life, providing a visionary alternative to conventional apartment blocks. For Safdie, as for many Jewish modernists, architecture was a way to envision a better, more equitable society—one shaped by principles of social cohesion and resilience.

Einstein Tower Potsdam photo Jean Pierre Dalbéra CC BY SA 2.0

The Appeal of Modernism to Jewish Architects

The prominence of Jewish architects in modernism is no accident. Here are some reasons why modernism was especially appealing to Jewish designers during the 20th century:

1. A Break from Tradition: Modernism’s rejection of ornamentation and historical styles offered Jewish architects a way to challenge societal norms and transcend their marginalised status. For many, embracing modernist design was a means of affirming a progressive identity unshackled from centuries of anti-Semitic stereotypes.

2. Urbanisation and Education: Jewish communities in Europe and the United States were highly urbanised by the early 20th century, often emphasizing education as a pathway to opportunity. This emphasis allowed Jewish architects and designers to access the avant-garde intellectual circles where modernism thrived.

3. Exile and Adaptation: Forced migration during the rise of fascism pushed Jewish architects to adapt their ideas to new cultural contexts. This process of reinvention not only spread modernist principles but also infused the movement with fresh perspectives.

4. Shared Values: The modernist emphasis on equality, functionality, and rationality resonated with Jewish intellectual and ethical traditions, which often emphasised community, social justice, and innovation.

A Lasting Legacy

The contributions of Jewish architects to modernism and Brutalism are not merely historical footnotes but enduring legacies that continue to shape the built environment. The sleek lines of mid-century modern furniture, the bold concrete forms of Brutalist housing estates, and the utopian ideals embedded in urban planning are all testaments to the influence of Jewish modernists who sought to transform society through design.

Their work also serves as a poignant reminder of the resilience and creativity of the Jewish diaspora. Despite facing persecution and displacement, Jewish architects and designers used the tools of modernism to create spaces that were both functional and visionary. Whether it was Marcel Breuer reimagining domestic architecture, Ernő Goldfinger building monumental housing projects, or Moshe Safdie proposing radical solutions for urban living, these architects left an indelible mark on the world.

Trellick Tower Image Louise Loughlin

Reflecting on Brutalism

The Brutalist brings these stories to life, offering a powerful homage to the architects who shaped modernism and Brutalism. By weaving together historical narrative and architectural exploration, the film highlights the ways in which Jewish values and experiences informed the movement’s ideals.

Modernist and Brutalist architects grappled with questions that still drive design: How can design address social inequities? What role does architecture play in shaping identity and community? Through their visionary projects, these architects challenged conventional thinking and dared to imagine a better future. The Brutalist makes us think, again, about these questions.

So, what does it all mean?

In the aftermath of the horrors of the Great War, that was supposed to be the very last war, a shattered generation saw in design a means of healing the world. But it was also a time when the world was being reshaped by prejudice and race hatred, and technological change. That there was a disproportionate representation of Jewish architects in modernism is because of the intersection of cultural values, historical circumstances, and, of course, individual genius. Jewish modernists brought a unique perspective to the field, yearning to be free of historical sterotypes and the persecution that went with them, blending innovation with a deep commitment to social and cultural renewal.

The legacy of these architects is not only found in the buildings they created but also in the enduring principles they championed—principles that continue to inspire architects and designers today. By celebrating this legacy, The Brutalist reminds us of the transformative power of architecture and its ability to reflect the complexity of human experience. With every raw concrete form and streamlined design, we see the indelible impact the modernists who turned adversity into art, building a future shaped by resilience, innovation, and hope.