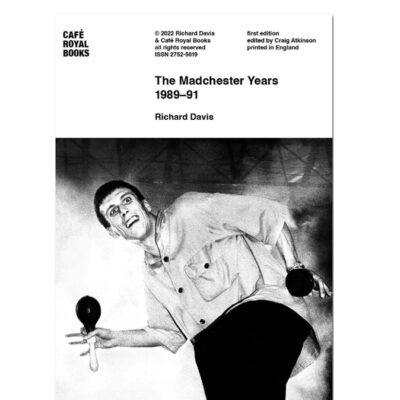

Richard Davis’ Backstage Pass to Madchester’s Cultural Explosion

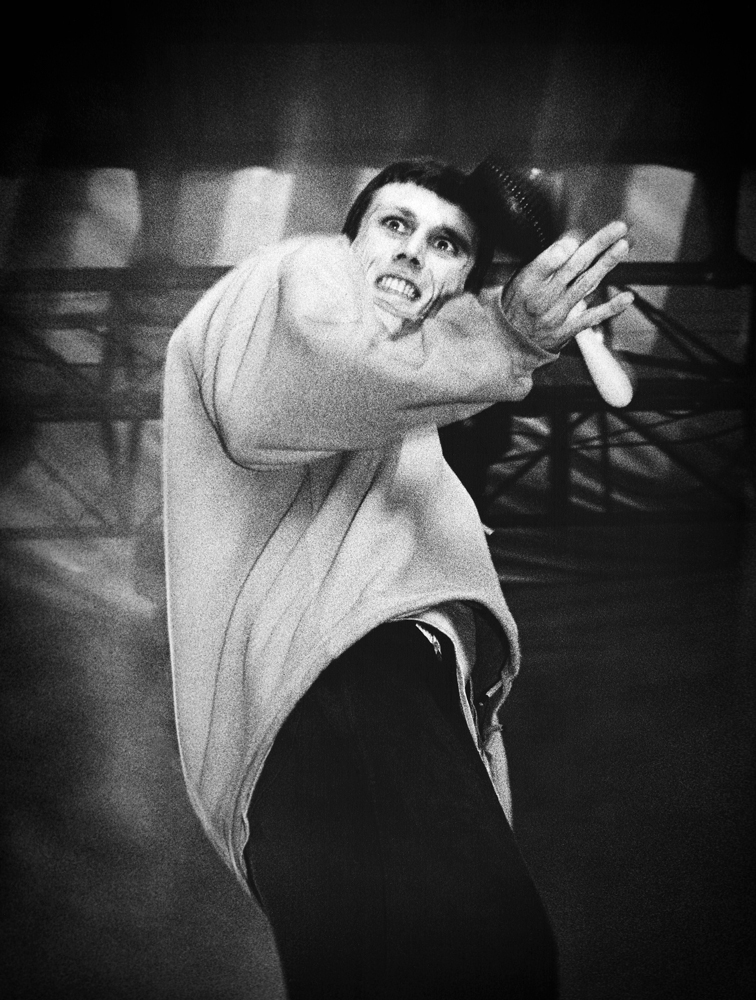

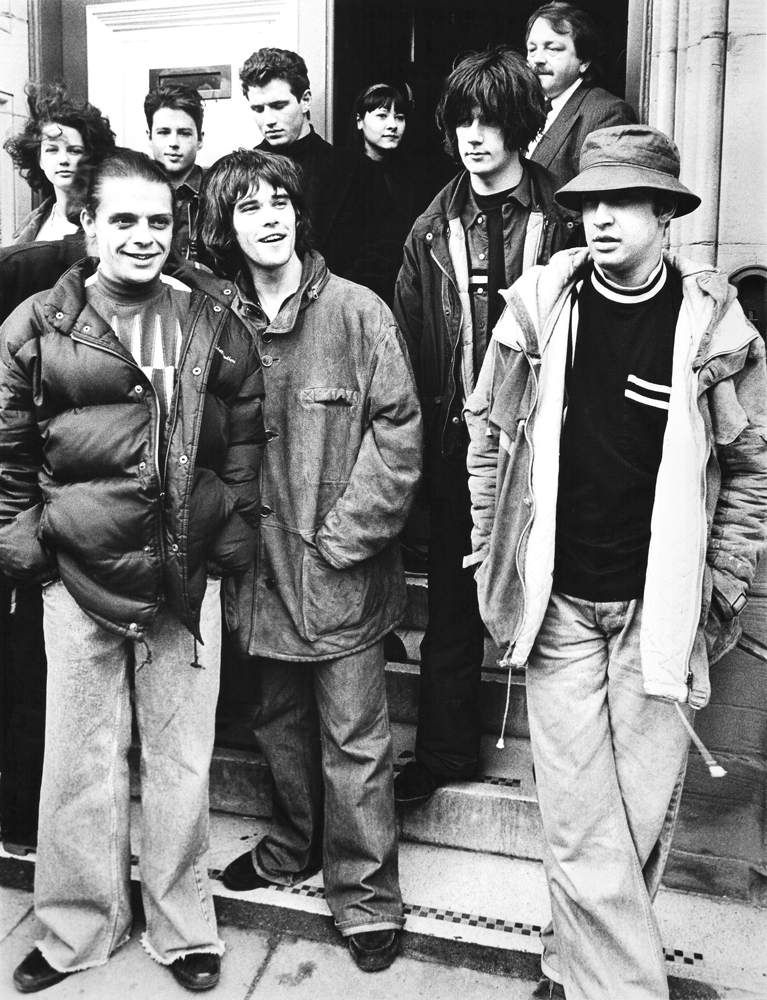

Bez Happy Mondays

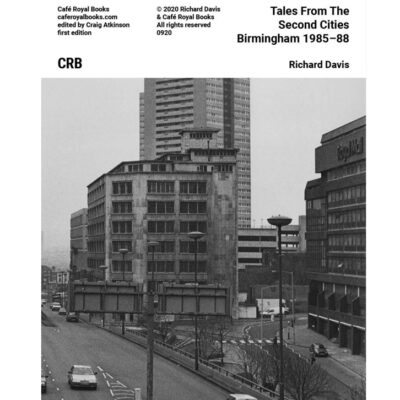

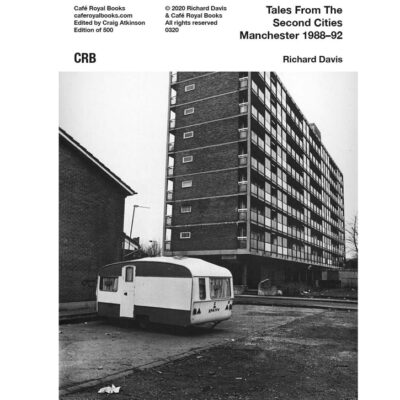

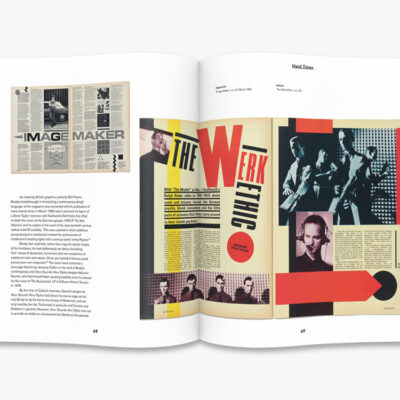

Richard Davis is among the most gifted British photographers of the last 40 years. His work captures the zeitgeist of 90s post-industrial, Thatcherite urban Midlands and Manchester, architecturally, musically and culturally; the Hulme Estate in Manchester, where Richard lived, at the start of his career, the emergent Manchester Madchester music scene, the breakthrough of the North-West’s alternative comedy and football in the last days before its transformation from working-class pastime to the wealth of the Premier League – and all the time buildings, buildings and buildings. We planned to interview Richard but instead, we enjoyed the most stimulating conversation for over 90 minutes with an artist who is a great artist because he has his eyes open, because he really sees and his photographs enable us to follow his gaze.

Hulme Crescent 1991

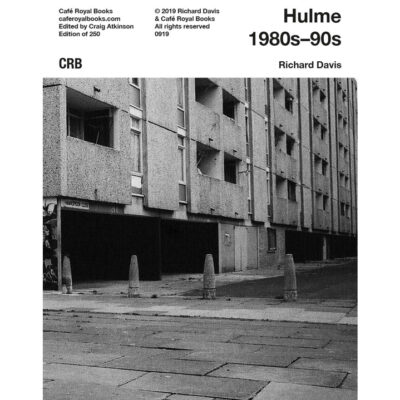

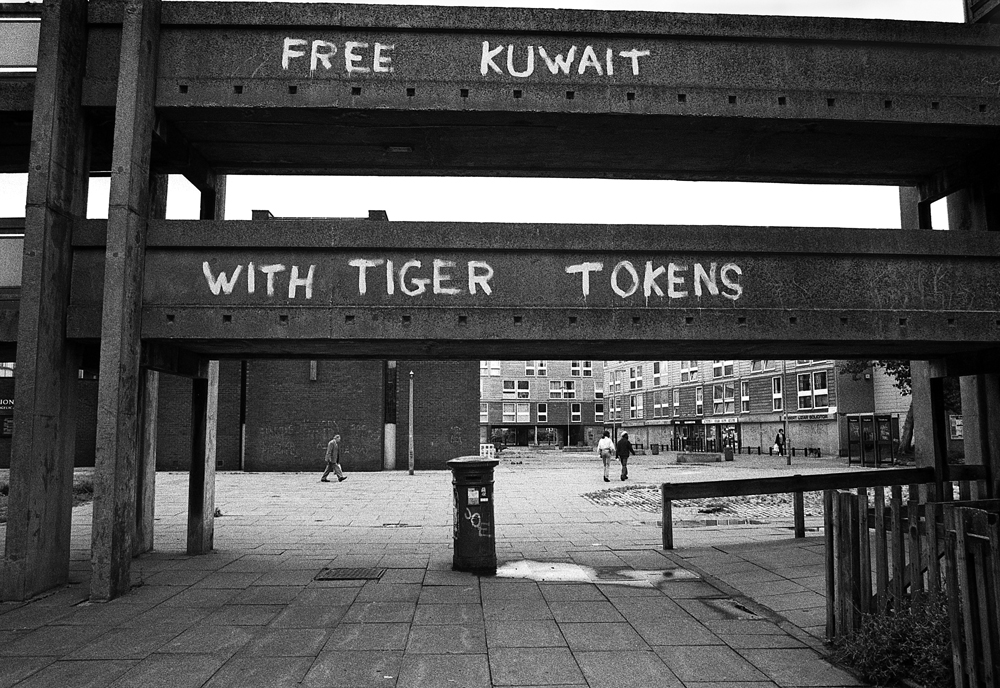

Richard moved from his home city of Birmingham to study photography in Manchester. Hulme Crescents was already failing a matter of a few years after being built in the early 70s. Design errors, poor promotion, a failure to consider the needs of the people slated to live there and a lack of funding to maintain and solve problems pushed the development into a familiar bitter spiral of neglect and disinterest. By the time Richard, a pretty much penniless student, settled into a squat in Hulme Crescents in 1988, its massive brutalist buildings were only half-inhabited.

Hulme Crescents was already failing a matter of a few years after being built in the early 70s

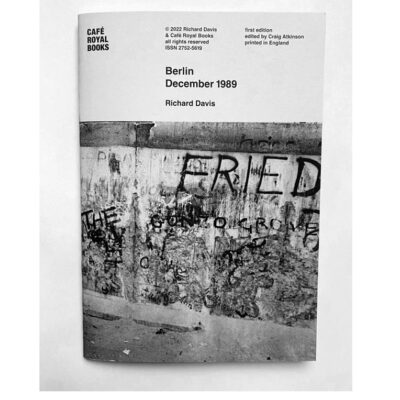

While he studied photography at Manchester Polytechnic, the city was in the throes of massive change from its great industrial and manufacturing past. From that turmoil sprang Madchester, a music scene steeped in indie-dance with a psychedelic direction from the 60s.

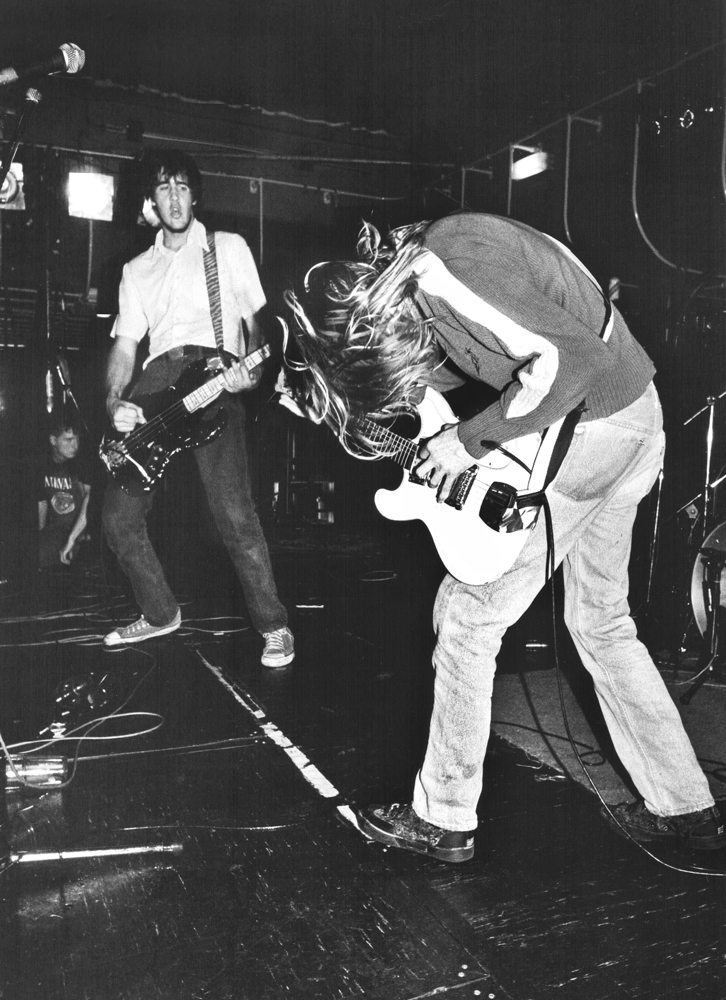

Nirvana, Manchester Polytechnic 1989

Stone Roses, Wolverhampton 1990

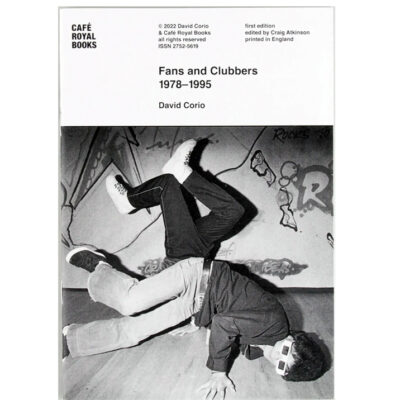

Original, challenging and more complex than Punk, a million miles from glam rock or the New Romantics, distinctly of the North and pioneered by bands including the Charlatans, Happy Mondays, The Stone Roses and, of course, the Smiths. Richard was there, photographing this creative overload as it spilled onto the streets. And at the same time Manchester birthed a revolutionary new comedy culture that blew away the tired and casually racist humour of the Northern club circuit. In London the Comedy Store and in Manchester the Comic Strip. Richard was there at the earliest moments of this new movement and his photographs caught its stars as they began their journeys.

Clint Boon, Inspiral Carpets 1990

Embedded in these overlapping, expanding universes of a distinctly Manchester culture was Richard, unobtrusively snapping.

Buildings are central to Richard’s work. He describes it like this:

‘I’ve done photography for 40 years now. And when I started back in 1983, I probably wasn’t interested in architecture but taking up photography made me start looking at my surroundings, looking at the world, looking at the patterns, looking at textures, looking at lines… I think that’s one of the beautiful things about photography, it makes you look at the world in a different way. And that’s what’s interesting for me, as soon as I picked up photography, and started rolling with it, I suddenly became aware of architecture and buildings and the history of buildings and everyday surroundings.’

Self-Portrait Hulme Crescent 1990

In these early days, in the massive, gloomy, chthonic Hulme Crescents, Richard learned to be unobtrusive. It wasn’t a good place to stroll around with a camera, so he’d go out early on a Sunday morning when few would be about;

‘… that tended to make the photos even more empty of people. I was doing black and white in those days. And because you had that really grey look and the concrete and the paving slabs which were completely chaotic. It made it really quite an odd environment.’

Mancunian Way 2023

Manchester, architecturally, has changed. Forty years ago it struck Richard as predominantly brick-built, red brick, but now it’s post-modern, growing up rather than out, ever more shiny glass towers;

‘What’s great is photographing the old and the new together before all the old is gone. It’s created such a strange looking city, you’ve got parts of old buildings, but then behind them all these glass, modern buildings. The city is changing its identity.’

Hulme Crescents 1991

We asked what went wrong with the Hulme Crescents. It was Europe’s largest public housing development, with over 3200 homes to house 13,000 people, finally demolished between 1993 and 1995, the policy decision having been made to clear the decks and start all over again. Hulme Crescents was meant to be a step forward, high-intensity housing but not in tower blocks, which were becoming so unloved around the country.

Hulme Crescents 1989

Richard’s view is that communities were broken up and moved from what certainly may have been grimy, cramped terraced housing, to the new homes where they were cut off from one another. The concrete walkways obscured views while the whole development was cut off from the city by a major road. Residents were barred from keeping pets and then a child had a fatal fall from the top of a poorly designed city-in-the-sky walkway;

The failure of Hulme Crescents is contrasted with the success of the Barbican

‘That’s when all the problems in Hulme started. I think that was only two or three years into it being occupied and they moved the families out again. It’s when Hulme became this strange place, half empty and half squatted, mainly for young people, no families no children.’

The failure of Hulme Crescents is contrasted with the success of the Barbican. It took a long time for it to be generally recognised but in the Barbican there’s a community in the heart of the city, not isolated by uncrossable roads, in a brilliantly designed estate, well-maintained and loved by its inhabitants.

Barbican Estate, Beech Street

Barbican Centre

What was it, we asked Richard, about Manchester 40 years ago that cooked up such a febrile creative mix?

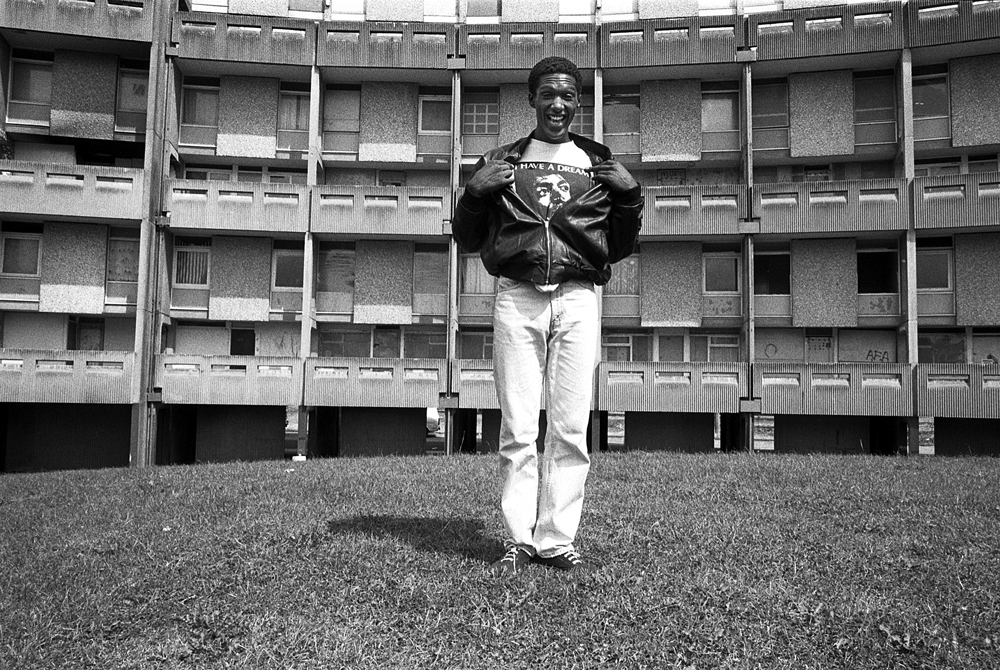

‘I think if you’re in an environment which is quite creative, or it’s full of people, enthusiastic people, not necessarily skilled but enthusiastic, motivated people doing creative things, that does rub off on you. And I think for me, definitely when I was in Hulme it coincided with a huge rise in Manchester in the late 80s. It wasn’t just the music scene but the comedy scene. Caroline Ahearne, Steve Coogan, John Thompson, Henry Normal, Dave Gorman, Jon Ronson, they all were friends. They all came along at the same time and they all encouraged one another. I started an arts collective in Lancaster about 15 years ago. And the idea was to try and recreate the scene and what I remembered of Manchester in the late 80s. I couldn’t do it. There was a different attitude. And no matter how hard I tried to put people together to collaborate, to soak up influences, see what worked, try to push the boat out, try something new, it wouldn’t happen. I think in Manchester in those days, we had a sense of freedom. There were no restrictions. And you kind of, like, think outward and you think big and you think I want to do something I’m gonna do it. Not, ‘we can’t do that.”

Lemm Sissay, Hulme Crescents 1990

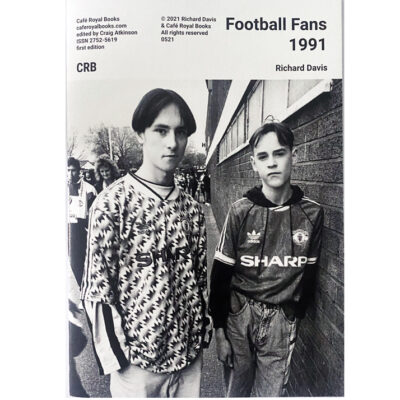

Richard’s art, his exquisite ability to seize the moment of people in a particular place, for example and famously, Nirvana when they first came to the UK, is perfectly suited to the drama and documentary truth of football. Not the drama on the pitch or the oh-so-glamorous badge-kissing players but the fans, the supporters. His football photographs document the last days of the game being the exclusive preserve of the working class before TV money, oligarchs, private equity and sovereign wealth funds elevated the Premier League and made its riches the goal of pretty much every club.

Maine Road Manchester 1991

Everton Fans, Goodison Park, Liverpool 1991

Looking back at the notes of our conversation with Richard, we find that he asked us as many questions as we asked him. Bit embarrassing, yes, but what it shows is an artist who’s always enquiring, always interested. Busy, well-known people don’t have the time (or inclination) to chat but in Richard, there is the ultimate observer, modest and unobtrusive but part of the story.

Midland Hotel, Morecambe 2021

All images are the Copyright of Richard Davis

A wide selection of Richard Davis’ photobooks for Cafe Royal Publishing are available from Greyscape