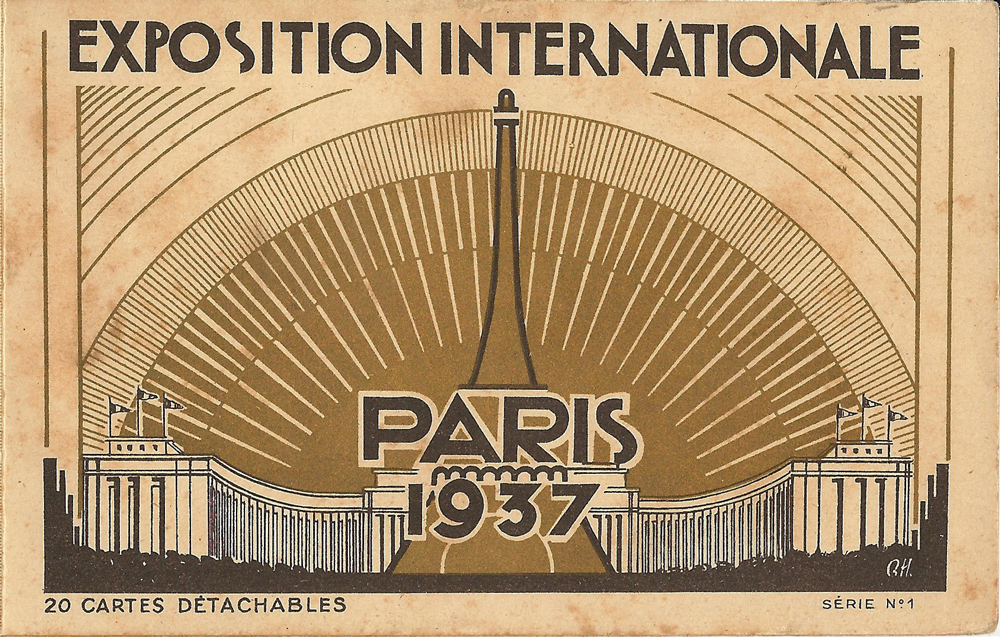

Exposition Internationale Paris 1937

Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne

Could there have been a more complex moment to take the temperature of the international community? From 25th May until 25th November 1937, spread across central Paris, from the banks of the River Seine to the foot of the Eiffel Tower, in the Champs de Mars and across the gardens of the Trocadero, the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne was showcased ‘Arts and Technology in Modern Life’. But it also allowed a group of nations to showcase the toxic ideologies of fascism, Naziism and communism.

A year later than intended, from an idea conceived in 1929, the Exposition finally opened in 1937. Even then it was not fully ready for its 31,040,955 visitors. The organisers had to open with some pavilions still under scaffolding, telling people to hold off attending until June. In reality the Exposition was not fully ready until July.

“last hope for peace in Europe”

The background politics in the run-up to the opening at times nearly overwhelmed the project. Sitting on the Exposition’s 42-person board were urban planners and politicians with much seat swapping; Robert Mallet-Stevens at one point stepped down and then returned, the original Chief Architect Charles Letrosne left in November 1935, replaced by Jacques Gréber with Robert Martzloff in charge of park and garden architecture. Perhaps the turning point that brought the whole project together was the June 1936 election that swept Le Front Populaire into power in France. The left-wing coalition government led by Léon Blum gave the 1937 Exposition Internationale Paris its fullest backing. Naively he described it as the “last hope for peace in Europe” However any attempt to steer this juggernaut away from becoming a gigantic propaganda tool for countries with competing ideologies failed miserably. Civil war had already broken out in Spain the previous summer and the Nazis and Soviets were using the war was as a test bed for their weapons and militaries. In a little over two years, Europe was to be plunged into a catastrophic war, with the world order altered beyond recognition in its aftermath.

While the Exposition hoped to showcase the best of architecture, artistic creativity, innovation and design it struggled under the burden of competing powers determined to use Paris to make clear their worldviews. You have to wonder why the Soviet and Nazi Germany pavilions faced each other with the Trocadero fountain in no man’s land between them? Inconceivable at the time, in August 1939 the two would sign a nonaggression pact to carve up Poland that held fast until June 1941 when Germany began its war of extermination in the east. In the sense of design and messaging, it was perfectly clear to architect Albert Speer (who persuaded Hitler Germany should take part in the Exposition and would become Germany’s wartime minister of armaments), that his German Pavilion in Paris should let the world know that National Socialism was a far better choice than Communism.

In all 46 countries participated, a selection noted here alongside a series of halls and sites showcasing French design and innovation as well as some of its own spoils of previous wars:

Pavilion of National Solidarity: Robert Mallet-Stevens and Rene Coulon

The Aeronautical Hall – the Palais de l’Air with frescoes by Sonia and Robert Delaunay and Albert Gleizes

Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau: Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret

Pavillon de la Lumière et de l’Électricité: built by Robert Mallet-Stevens featuring Raoul Dufy’s La Fée Electricité

Thermalisme: Georges Labro

Palais de la Découverte: Armand Néret and Maurice Boutterin

Musée de Arte Moderne: Dondel, Aubert, Viard and Dastugue

German Pavilion (standing squarely opposite the Soviet Pavilion) designed by Albert Speer who claimed to have seen the design and purposely countered its message – flying the swastika. Showed Nazi propaganda films

Soviet Pavilion designed by Boris Iofan focused on technical achievement. Sitting on top of the pavilion was Vera Mukhina’s socialist realist stainless steel ‘Worker and Kolkhoz Woman’ two figures with raised arms holding a hammer and sickle above their heads. The sculpture was moved to Moscow when the exposition closed.

British Pavilion : Oliver Hill with a frieze by John Skeaping

Italian Pavilion: Marcello Piacentini, Arturo Martini and Giuseppi Pagnano with clear references reflecting the supposed positive aspects of living in Mussolini’s Fascist Italy

Spanish Pavilion: Josep Lluis Sert, included Alexander Calder’s Mercury Fountain, works by Miró and the artwork that caught the world’s attention, Pablo Picasso’s Guernica.

Belgian Pavilion: M M Van der Velde and Eggericx Verwilghen-Schmitz

Palaid d”Iéna by Auguste Perret

American Pavilion: Paul Lester Weiner

Dutch Pavilion: Jo Van den Broek

Romanian Pavilion: Duiliu Marcu

Pavilion of British Mandatory Palestine ‘ Pavilion of Israel in Palestine’ located in the Trocadero moments away from the German and Soviet pavilions: Tamir and Grinshpon

Palais de la Radio

Palais du Bois – The Timber Pavilion

Pavilion of Hygiene: Robert Mallet-Stevens and Rene Coulon

Palace of Electricity and Light Robert Mallet Stevens with Georges-Henri Pingusson

Pavillon des Tabac, Tobacco and Match Pavilion: Robert Mallet-Stevens

Palais de Chaillot (rebuilding of an original building): Louis-Hippolyte Boileau,. Jacques Carlu and Léon Azéma

Palais de Tokyo originally called Le Palais des Musées d’art moderne and Musée de L’Homme permanent structures built for the exhibition

Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux (new times) designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret

Finish Pavilion: Alvar Aalto

Canadian Pavilion located at the foot of the Eiffel Tower included the work of Joseph-Émile Brunet

*Shaping the Eposition Suny Press