British Brutalist Architecture Through Russian Eyes

Why a Moscow student of Architectural Design just happens to love the Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate, and Trellick Tower in London

Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate Image A.Bobina

Alisa Bobina was born in the ancient city of Yaroslavl, which she describes as a beautiful tiny calm oasis. It is 280 kilometres from Moscow. She is now in her fifth year studying Architectural Design at MArchi, the Moscow Institute of Architecture

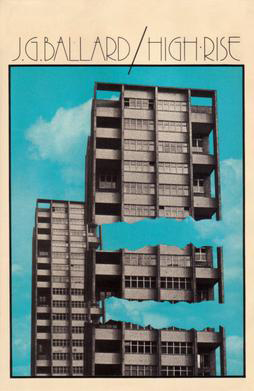

‘I’m fascinated by English brutalist architecture. My interest was initially triggered by reading James Ballard’s novel High-Rise, its depiction of the effect that a building can have on the human psyche. It is very powerful. Brutalist architecture is enigmatic, mysterious and rather breathtaking’.

‘There is something about the monumental design, the way motifs and patterns are frequently repeated, all set within rough concrete surfaces. I read that Trellick Tower was the inspiration. It was odd to realise that despite coming to London many times I had never paid real attention to brutalist architecture, so that was my next trip planned! To visit the best examples and capture them on my camera, armed with a book I bought called ‘Brutal London’ as my guide. Amongst the earliest places I visited was the Barbican and Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate. My first impression was really good, I had never seen places that looked like this before!”

Trellick Tower London

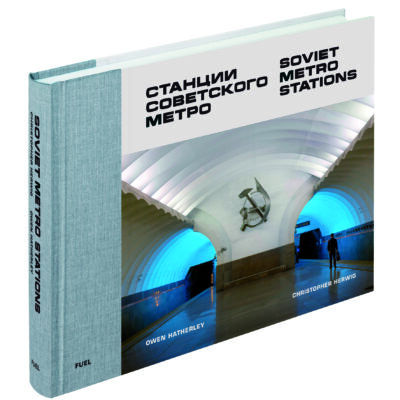

This is very different from Alisa’s experience growing up. Yaroslavl is an ancient city, one of the ‘Golden Ring’ group of cities around Moscow. Its historic centre is a UNESCO World Heritage site. To many non-Russians, the Soviet era is inextricably associated in their minds with huge monolithic architecture. But Stalin rejected the Constructivism that so optimistically heralded a revolutionary new architecture. Stalin’s Empire style, dominated from 1933 until 1955 and certainly was monumental but technologically old-fashioned, masonry built rather than employing concrete and much of the construction used traditional methods and materials notably timber floors and partitions. Brutalism, as it developed in Britain, was very different.

The Red Army Theatre in Moscow, designed in a shape of the Soviet Red Star Image: Alex ‘Florstein’ Fedorov CC BY SA 4.0

The ‘Seven Sisters’ Moscow 1947-1953 Image: Howard Morris

We asked Alisa her feelings about British Brutalism.

Did you get to see Erno Goldfinger’s Trellick tower? It’s often mentioned in connection with High-Rise, though it was never a luxury apartment block.

Yep, a couple of times. Standing beside a building of the stature of Trellick Tower, I felt like a tiny grain of sand. It’s fascinating to consider what the interior of the homes might be like and how their design has impacted and influenced daily lives.

Trellick Tower, London Image: A Bobina

Do you see any comparison between Trellick Tower and residential apartment blocks in Russia? Did the theme of J D Ballard’s High-Rise ring any bells?

Thank goodness – no!!! (High-Rise is a dystopian tale of what happens when the lives of the residents of a Brutalist apartment block spiral out of control). Although I could relate to the description of the type of building, however, there simply isn’t anything one can compare it to in Russia. Almost everyone lives in multi–storey apartment blocks unlike anything in England. Our Constructivist buildings are interesting, with socialist ‘ideals’ built into the design.

Narkomfin Building Image: Howard Morris

For example, the Narkomfin Building in Moscow, which I had the opportunity to visit during its recent renovations. It is well worth seeing although you had to really use your imagination to get a sense of the original interior design. The inner wall of the apartment I visited had been destroyed.

The Narkomfin building was a hugely ambitious project based very strongly on socialist ideals. It was to be home to the families and staff of the Soviet Ministry of Finance, providing accommodation, communal dining, care for the children and healthcare in one great building. But Narkomfin fell into disrepair and only in the last few years has a private-sector project to lovingly restore the building and its apartments brought it back to life as high-end private flats.

Narkomfin Building, Moscow Image: A.Bobina

Image: A.Bobina

Image: A.Bobina

During 2019 renovations Image: Howard Morris

Narkomfin Building Moscow Image Howard Morris

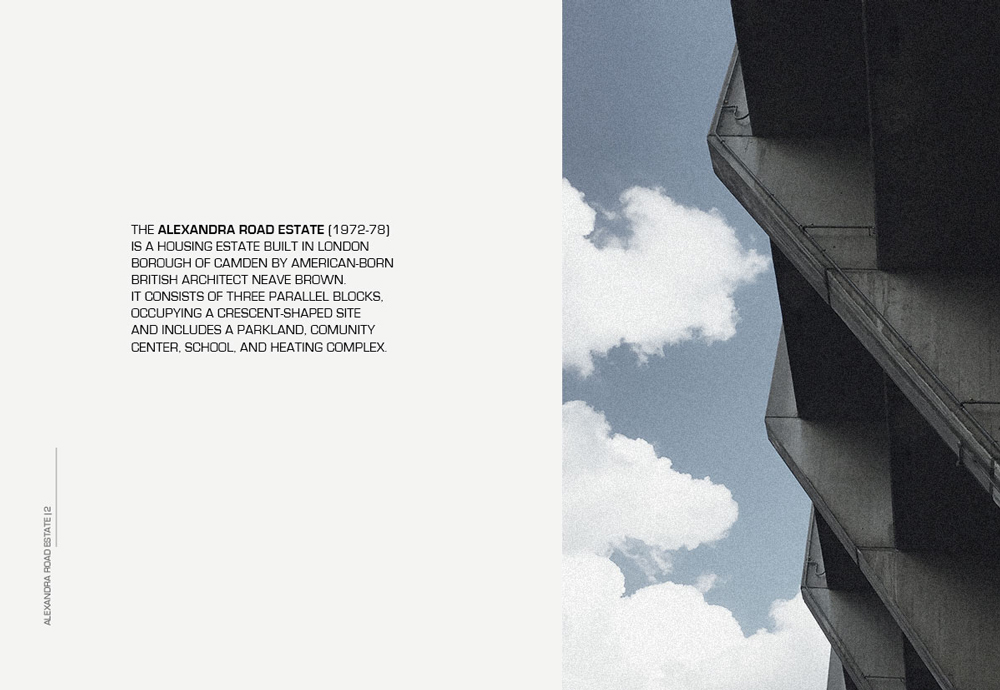

Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate

Why did you choose Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate for your Architectural Zine?

To convey my first impressions from the perspective of someone coming from a very different urban environment. It’s clear from the powerful designs that you can still sense the spirit of the late 1970’s and of the architects’ thinking. The photos allowed me to describe my own impression of one of the most fascinating Brutalist housings developments in London. Actually, it is a pure architectural treasure and a great example. It clearly reflects most of the principles of brutalist public housing. You can spend here all day discovering new incredible features.

Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate Image: A.Bobina

The unusual construction is really striking considering that this is a residential building. It is not vertical in a conventional way and every tenant has the space to create their own garden on a terrace. It was one of the first English brutalist buildings I’ve ever seen. When I found it, I was completely impressed by its monumentality and it was all made of concrete, even the seats! Its structure consists of three parallel blocks, occupying a crescent-shaped site and includes parkland, a community centre, a school, and its heating complex.

Neave Brown’s Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate Image A.Bobina

Neave Brown, the estate’s architect, won the Royal Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects RIBA in October 2017 and died January 2018. Rowley Way, which a lot of people call the Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate, is credited as the first post-war council estate to be listed. What are your thoughts about how Brutalist architecture has impacted on the resident experience?

Rowley Way is clearly a success story, that is not the case for all Brutalist estates. Some have ‘succeeded’ and others have not, a factor is their design. At one level Brutalist buildings look really cool and monumental, with well thought out infrastructure, such as distance to local schools and amenities. However, it’s hard to describe them visually as friendly, I’d leave that description to Finnish and Swedish contemporary housing, there’s a lot to be learnt from their designers and how their social housing estates are managed. One obvious exception is the Barbican Estate, its layout is very impressive.

Russian Social Housing

What’s it like?

The most common type is the Soviet housing block systems. They are known as krushchyovkas or more commonly, and a bit more bluntly, they are known as khruschoba. Immediately after WW2, it became clear that there was a drastic housing shortage. Under Nikita Krushchov, a programme was created to quickly erect block housing to alleviate the problem of overcrowded cities. The national Krushchyovka block housing building programme was the answer. They feel precisely like what they are … industrial and prefabricated. For the tenants, they were a big improvement on their predecessors’ kommunalkas, multi-family flats.

Khrushchyovka Image: Zharov Anton Alekseevich CC BY SA 2.5

What is it like living in a krushchyovka?

To be honest, I never have lived in one! My friend does, so what I can say about them is that they are tiny flats (from 30 to 50 square m) with low ceilings and rooms aligned with each other and they can smell quite musty. This is a design fault as much as an issue of age – some homes were built with tiny bathroom windows and loos located where there was little ventilation and natural light. Added to that the windows were poorly designed so there was a problem about insulation in a very cold country. I once read that the inner walls were built to withstand gas explosions because Krushchyovkas and Brezhnevkas (later and larger versions of Krushchyovkas) didn’t have adequate hot water systems. The problem today is that they are now more than 50 years old they are generally in need of repair, but no one wants to tackle the issue, in Germany, there are similar homes however there has been a programme to refurbish some of them.

I’ve read that there is a programme in some places to demolish krushchyovkas, what happens to the residents? Are they automatically rehoused in the same area?

In Moscow, mostly all that has happened is the demolition, outside Moscow, many people simply continue living in their apartments regardless of their condition.

Demolition of Moscow Khrushchovka Image Artem Tkachenko CC BY SA 4.0

Architecture Favourites

With your fascination for architecture and the built environment, which architect particularly inspires you and speaks to what you would wish to achieve one day?

I really love the work of David Chipperfield, in particular, his reconstruction of the Neues Museum. I’m also a fan of some of Daniel Libeskind’s buildings, especially the Jewish Museum in Berlin, it very powerfully conveys the feeling of pain, fear and despair. This is architecture which can speak to people.

Any stand-out inspiring buildings you love?

In Berlin, I was really struck by Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation. Whilst it’s not pure Brutalism, Corbusier was the father of it. I suppose the original idea which fueled the creation of such huge Brutalist estates was the desire to create a socially cohesive community living in a ‘city within a city’, a designed space filled with public spaces and inner courtyards where people could meet accidentally or purposefully, where they could talk, walk, work, and rest.

Unite d’Habitation Berlin Image A.Bobina

Modulor Image A.Bobina

Unite d’Habitation Berlin Image: A.Bobina

What are your thoughts about Corbusier’s connection to Russian architecture?

He built the Tsentrosoyus building, the Central Union of Consumer Cooperatives in Moscow together with Nicolai Kolli (1928-1936). It was his only building in the Soviet Union. Some of the concepts Corbusier used were later employed by Russian architects in the building of the Khrushchyovkas.

Tsentrosoyuz Building Moscow (Corbusier and Nicoli Kolli) CC BY SA 4.0 Image Ludvig14

Current Projects

What are you up to at the moment?

Graphic design fascinates me and I really enjoy creating posters and CD covers. I’m continuously developing ideas, some are projects connected to my studies. Last year I created a cover for a book called ‘Colour in Architecture and Art forms in world culture. Graphic artist Chris Ashworth is a firm favourite.

We’d love to hear about your home city, Yaroslavi

It’s home to 600,000 people, minute in comparison with Moscow which is home to 13 million. Oh my, when I moved there – culture shock!. There’s lots of really old, tiny houses and the notion of a high rise doesn’t exist – I suppose the highest building in the whole city is 16 storeys. It’s a very restful place but if you have ambition it has limitations for a young person. Notwithstanding, I love Yaroslavl so much, many friends and family live there, and I frequently visit.

Stuff we love to know

Fav song At the moment it is Depeche Mode’s Dream On. Actually, I’m a big fan of British music (love artists like Pink Floyd, Muse, Suede and David Bowie). I’m open to different music styles, be it rock, metal, electronic, some of the cold-wave and synth’s flows.

Books George Orwell, Haruki Murakami, A Clockwork Orange, and B is for Bauhaus: An A-Z of the Modern World by Deyan Sudjic.

Film Blade Runner

Local food we should all try one day? Hmmm… meat dumplings, in Russian their known as Pelmeni and Pastila, which is a fruit confection. Out of town, I’m a big fan of Caesar Salad, definitely not part of the traditional Russian cuisine.

Follow Alisa on Instagram @floccinaucci and @_neofactory

All noted images copyright of Alisa Bobina and Howard Morris

A Snapshot from Alisa’s Photo Zine

Front Cover of Alisa’s Alexandra Road Photo Zine